Welcome to the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF), the world’s largest science competition for high school students. Out of the tens of millions of students who enter science fairs around the world each year, just 1,800 qualify to participate in this one.

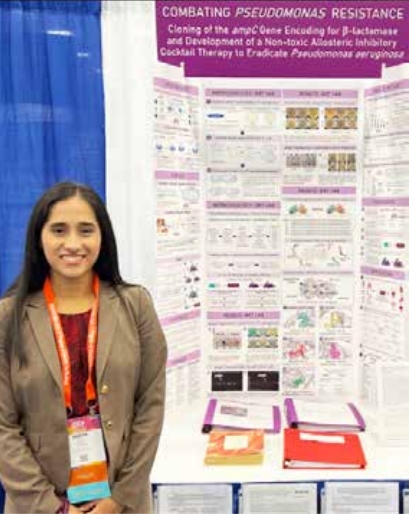

Shriya Bhat not only attended this elite competition—she won! In both 2022 and 2023, she got frst place in the microbiology categor. “I was super shocked,” she says. “I thought I had done a really great job and I presented my science well … but I was not expecting that.” At the time, she was a student at Plano East Senior High School in Texas. Now, she attends Harard University where she’s studying molecular biology and planning on a career that includes scientifc research.

ISEF and other science competitions help curious kids become successful scientists. Dianne Newman is a microbiologist who attended ISEF back in 1987 and 1988. She told Science News Explores that this was “a totally formative experience that changed my life. It gave me a taste of how much fun research can be, and how much joy there is to be able to share your research with others.” She said the competition helped her realize that she could have a successful career as a scientist—which is exactly what she went on to do.

Even people who don’t plan on becoming scientists learn a lot from science fairs. Participation teaches you how to plan and manage a long-term project, how to solve problems, how to work with peers and mentors, and how to communicate your ideas to others. All of these skills are useful no matter what career you end up choosing. Bhat said that these competitions foster “confidence and independence.”

Choosing a Project

Ideally, working on a science fair project doesn’t feel like a chore. You should feel enthusiastic about the experiment you’re pursuing and motivated to find answers to your scientific questions. Real passion for a field of science is something judges look for. Newman said, “Try to find a project that stimulates you. That you’re genuinely curious about. And then, push yourself to explore it as rigorously as youcan.

Bhat agreed that you should choose a project that you feel motivated to work on. “A good foundation is fguring out what general feld you really enjoy asking questions in,” she said. That might be machine learning, plant science, physics and astronomy, or any one of the twenty-two categories ISEF divides projects into. Pretty much anything that interests you has potential to become a science fair project. Do you like music? You could do a project related to acoustics or bird song. Enjoy sports? You could look into sports medicine or spors technology.

Once you’re interested in a feld, Bhat said, you should pay attention to what questions experts in the field are asking themselves. Those are questions you could be exploring too. You can find out what’s happening in a field by reading recent scientific research papers—Google Scholar is an excellent place to search for these materials.The discussion section of a paper usually includes questions that the study wasn’t able to address as well as ideas for future research directions. You can also come across great ideas by listening to scientific podcasts about a field, watching online talks, or even attending lectures or conferences. The research Bhat did while developing an idea took up about 30 percent of the total time she spent on each project, she estimated.

Research papers can be intimidating—they are filled with technical jargon that can be ver difcult to understand when you’re new to science. Bhat’s approach was to read the abstract frst, then read the introduction, and then look at the figures. High school students today, she said, have a big advantage. “There are these really helpful AI tools,” she said. Students can use ChatGPT or Claude or another bot to summarize a research paper, defne new terms, or explain sections of a paper in a way that’s easier to understand.

“These tools aren’t perfect,” Bhat said. They sometimes get things wrong. But as long as you think critically while using them, they can help make tricky science more accessible.

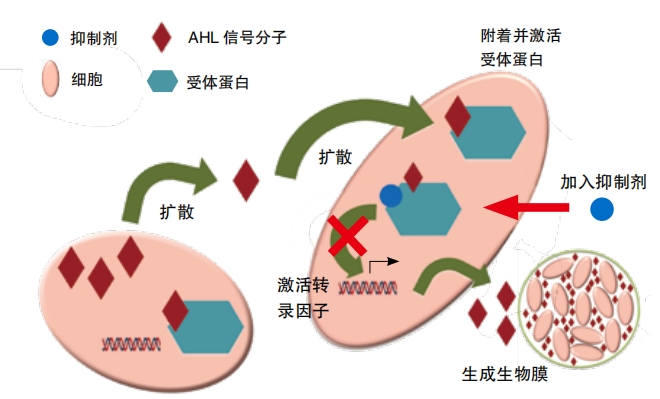

Even before Shriya Bhat came up with her science fair project ideas, she knew she was interested in microbiology. While she was learning about the feld on her own, she watched a TED talk titled “How Bacteria ‘Talk.’” It was about bacterial communities called biofilms that have a sort of chemical language that they use to coordinate their behavior. Bhat remembered thinking, “Wow, that is so fascinating.”

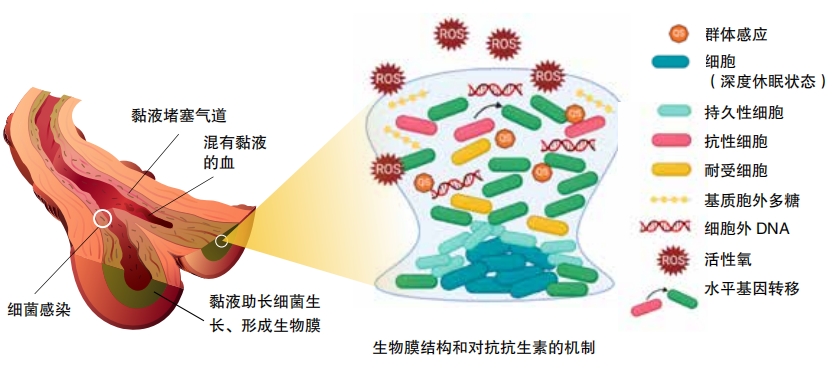

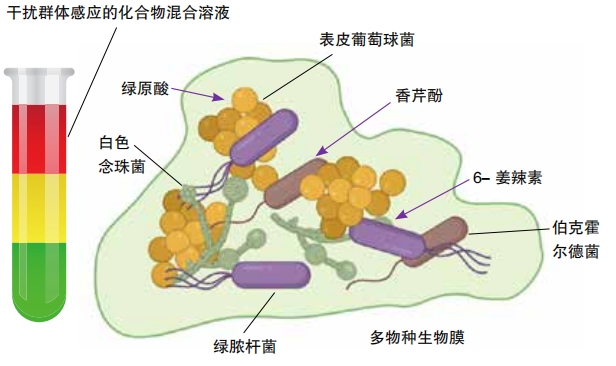

Bioflms are a big problem in several types of disease, including the lung disease cystic fbrosis. This disease causes a sticky mucus in the lungs, a type of environment where bioflms thrive. So many people with this disease end up with recurring lung infections that don’t respond to regular antibiotics. Bacteria living in a bioflm can be ten to one thousand times more resistant to typical antibiotics than bacteria that aren’t par of such a community. Bhat wondered if messing with the chemical language might help people destroy bioflms. So over the next few years, her projects explored “whether we can break this communication.”

Once you’ve found a project idea that seems interesting, you should ask yourself a series of questions to make sure it is a good choice:

-How can this experiment make a difference? Your project should have the potential to contribute to science or society in a valuable way.

-Who is already doing this type of research and what have they discovered? You don’t want to repeat something that someone else has already done. Look for ways to expand on the work of others. Make sure you think about what the expected outcomes of your experiment will be. This will become your hypothesis.

-How difcult will the experiment be? Be honest with yourself about how hard it might be to understand and investigate your idea. If it is too expensive, too dangerous, too challenging, or will take a very long time, you might not be able to complete it. However, you also don’t want it to be too easy, or it won’t impress the judges.

Finding Mentors

In the real world, scientists almost never work alone. Most major scientific advances happen in very small increments as many different labs filled with researchers work diligently to solve a problem. Students working on science fair projects also need collaborators and supporters. A mentor is a special kind of supporer who has experise in the feld and can guide you as you develop your idea, perform your experiment, and analyze your results. You should identify a mentor early on in your science fair journey and ask them for feedback at ever stage of your project. However, it’s imporant that you are the one leading your project, perorming experiments, and making all the decisions. Science fair judges look for evidence that your project is your own work.

High school teachers commonly act as mentors for budding scientists. Kelly Benoit-Bird is a marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. She was the first person in her family to go to college. She told Science News Explores, “I didn’t come from a family background that understood research opporunities at all.” In high school, she stared studying dolphins for fun. Her teachers encouraged her to pursue this passion, and she wound up competing in ISEF in 1994. “I was so fortunate to have some really strong mentors in my high-school biology and physics instructors,” she said. “ I think people in general are really excited to suppor students when they are following their passions.”

Bhat said that her biology teacher, Julie Baker, gave her the courage to ask questions about biofilms and do her own original experiments. “She was a tremendous resource,” said Bhat. She gave her students advice on how to conduct their experiments and on how to present their work so others would understand it and care about it, Bhat said.

Teachers aren’t the only people who can help with a science fair experiment, though. Bhat said that upperclassmen at her school really helped her out. They had experience paricipating in science fairs already. She also reached out to working scientists. Usually, their contact information is publicly available on their websites or in their research papers. (The “corresponding author” is the person responsible for answering questions about a scientifc paper.) “I was emailing professors all the time, asking for input,” she said. They didn’t always respond, but when they did, “I got some valuable insights,” she said. For a large part of her freshmen year, she did her lab work at a local community college. The lab belonged to a professor who was also studying bioflms.

“You shouldn’t feel intimidated by the idea of contacting scientists,” Raj Chetty told Science News Explores. He is an economist at Harard University who paricipated in ISEF in 1997. At the time, he was studying cell biology. “It’s worh just reaching out to folks. I think lots of people want to help the next generation,” he said.

Conducting an Experiment

Once you have a project idea and a mentor, it’s time to start experimenting—almost! Before you get out the test tubes, you should make a detailed research plan that follows the scientifc method. Here are the most imporant sections to include:

-Rationale: Describe the problem you are investigating and why it matters in a brief statement.

-Research question: Explain your hypothesis. This includes the expected outcomes of your experiment.

-Procedures: Describe step-by-step how you plan to carry out your experiment. Include any equipment or tools that you will need.

-Risks and Safety: Identify any safety equipment you will need or precautions you will need to take.

-Data Analysis: Explain how you plan to analyze your data or results.

-Bibliography: List all the research sources you used to develop your idea and research plan.

Bhat knew she was interested in biofilms and how to stop these communities of bacteria from communicating. Her rationale for her research was that it could help people with cystic fbrosis who are struggling with recurring lung infections that can’t be treated with typical antibiotics.

For one project, Bhat picked three substances that were each known to interfere with biofilm communication, also called quorum sensing. Each substance was a chemical compound that blocked communication between two diferent types of microbes. These compounds had all been approved by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) as nontoxic, so safe for use as medications and in her research. Her research question focused on fnding out whether combining these compounds into a cocktail treatment might be more efective against bioflms than any of the substances alone.

Her procedures included analyzing the types of microbes often found in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis and chronic infections. Then, she ran simulations that predicted how well the cocktail should work Finally, she grew bioflms in a lab and tested the cocktail. “I tested various treatments of compounds at diferent time points, both as inhibitor and killing agents,” she explained.

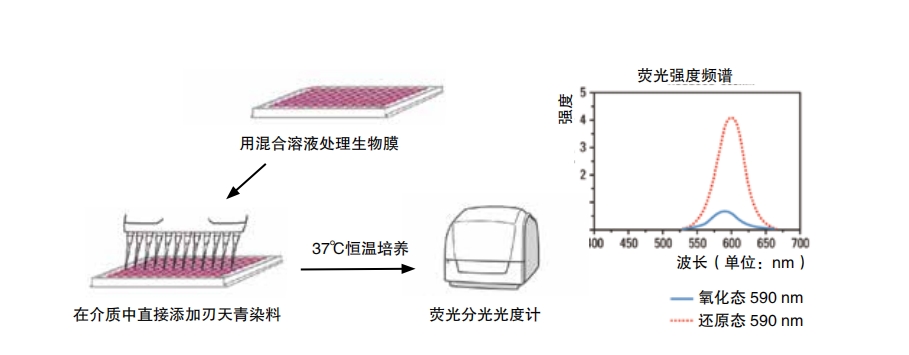

During the experiment, Bhat needed to regularly check on the bioflm’s growth. At frst, she did this using a technique called crystal violet staining. This revealed how massive a biofilm was, but not how many of the bacteria inside were still alive. So later she switched to a technique that uses a dye called resazurin. Living cells change its color from blue to pink, so this dye can reveal how many living cells are inside a bioflm.

As you work on your plan, begin thinking about how you are going to get the materials you need. Many science experiments will require specialized tools and safety equipment. Bhat’s school provided some of the basic materials she needed, and the labs she worked in provided some equipment as well. But, she said, “I had to buy a lot of these materials myself.” You may need to fundraise to collect money so you can afford to do your experiment. Bhat applied for school-level grants and got one that helped pay for her research. “I did have to suppor myself and really advocate for myself,” she said.

Also make sure to set aside enough time to do your experiment. “I did most of my research during the summer,” Bhat shared in a 2024 YouTube video she did with fellow ISEF winner Rishab Jain, who received a 2022 Regeneron Young Scientist Award and is now studying neuroscience at Harard University. Bhat said she spent seven to eight hours per day in the lab ever work day all summer long. Jain said he also mainly worked on his project over the summer and on school breaks. You have to think of the experiment as “a fulltime job,” he said. “You’re putting a lot of dedication into your research.” On a typical day in the lab, Bhat said, she was “growing bacterial cultures, isolating the biofilm, and adding combinations of treatments at optimal concentrations both after and before growth.”

For her junior year ISEF experiment, Bhat tested a cocktail treatment that turned out to be 80% effective at stopping the growth of a biofilm that contained multiple types of bacteria. Her senior year experiment tested a different cocktail that targeted a biofilm containing P. aeruginosa. This treatment was 90% effective. So both cocktails show promise as possible new therapies for the life-threatening diseases.

Jain points out that some students feel discouraged if their experiment doesn’t get excellent positive results. In the AI realm, he said, “when you come to ISEF, it seems like everone has 99.9% results.” That means their idea worked almost 100% of the time. “You don’t need to have that top number,” he stressed. “70% accuracy may be more impressive for a specifc project than 99.9% for some other project,” Jain explained. No matter what your results are, you can frame your research to show how it helps move science forward.

Wowing the Judges

At the high level of ISEF, Bhat explained, “everyone is doing amazing work.” In order to stand out, you really need to wow the judges. ISEF judges award a maximum of 100 points divided up across five key areas. The research question receives up to 10 points. Here, judges are looking for a testable idea that contributes to your area of science. You should state it in a clear, focused manner.

The category of design and methodology receives up to 15 points. This part of judging looks at the way you planned your experiment. Top points go to experiments that are well organized with well-defined variables and controls and excellent data collection methods.

A maximum of 20 points is awarded for execution, which includes data collection, analysis, and interpretation. This part of judging looks at how you actually carried out your experiment. Your process should be careful and systematic—it should be straightforward for someone else to reproduce your experiment. It’s also essential that you collected enough data to suppor your conclusions and applied statistical methods appropriately.

Judges place special emphasis on the final two categories. Those are creativity (20 points) and presentation (35 points). A creative project is original and inventive, or opens up new avenues of inquir for furher research.

The presentation categor includes two pars: a visual poster worth 10 points and an interview with the judges worth 25 points. This categor is especially imporant because an amazing discover can only move science forward if people know about it.

Communicating the results of research in a clear and efective way is a key par of science and, therefore, essential to doing well in a science fair. Bhat had taken public speaking classes and had paricipated in speech and debate all through high school, so she was well prepared for presenting in front of the science fair judges.

Bhat expressed that enthusiasm is an especially important part of a successful presentation. Every single time you present your work, she said, “bring that same energy.” Jain said his presentation style is a bit diferent. “How you present should be matching your personality,” he said. “My ‘wow’ factor is basically just being a nerd.” He said he knew so much about his feld that he could really connect with the judges, even on topics beyond the scope of his project. And that’s imporant since the judges aren’t just looking at your current work but at your future potential as a scientist. “They want to see that this award is going to encourage you to continue pursuing that passion,” said Bhat.

Clarity is also essential. If people don’t understand what you’re working on, said Bhat, you’ll lose your audience. According to her, it’s critical to break your ideas down to a level that “literally anyone could understand.” Keeping things brief can help with clarity. It’s also imporant to be brief with your presentation so that you leave time for questions. At ISEF, a judging interiew takes ffteen minutes. And judges don’t just want to listen; they want to talk with you. During the interiew, you should be prepared to discuss your feld in depth with expers. But also have fun and be yourself.

Diagrams, graphs, and images are another imporant par of an efective presentation. The poster, also called a board, explains your experiment and results. Bhat said she used “as many diagrams as possible” when designing her board but really limited the number of words. Jain had a different approach. “I like to put as much information as possible to show that I did as much work as possible,” he said.As in the interview, your board should refect your personality. Bhat’s was pink and purple! Ever board should have a visually pleasing design and should convey all the essential information about the project.

Bhat thinks her choice of experimental topic helped her win first place. “There were not a lot of biofilm projects at the international level,” she said. “But it is a huge problem.” So her idea was creative and also had the potential to help society. She also thinks her level of independence in managing her project and advocating for herself mattered a lot. She said she showed the judges that she was not someone who “has had everthing handed to her.”