The rule of law demands that similar cases have similar outcomes. Otherwise, the law won’t be equitable and fair. And the public won’t accept arbitrary court rulings that lack sound reasoning. So, lawyers use reasoning when they urge juries and judges to rule for their clients. And judges must use logic to explain their decisions.

In practice, legal arguments often combine different forms of reasoning. In a criminal case, for example, lawyers for the government act as plaintiff, the suing party, and want the court and jurors to know who got hurt when someone broke the law and why it matters. .

Lawyers must prove their cases with witnesses, documents, or other evidence. Evidence is anything that makes the required elements in a case more or less likely to be true. Both sides get a chance to introduce evidence and make arguments.

For example, deductive reasoning by a government lawyer in a criminal case might take the form of a syllogism:

•“The judge will tell you that if anyone does A, B, and C, then that person is guilty of crime X. ”

•“The evidence shows that the defendant did A, B, and C. ”

•“Therefore, members of the jury, you should find that the defendant is guilty of crime X. ”

However, deciding that the evidence shows A, B, and C may require inductive reasoning or even abductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning makes inferences based on observations, either by analogy or by generalization. Abductive reasoning looks at a combination of evidence and infers the best explanation for it after considering whether other explanations would also be reasonable.

In the United States and British legal systems, criminal cases and many, but not all, non-criminal cases provide a right to trial by jury. When that happens, the jury decides questions of fact. And in all cases, the judge decides questions of law. The judge also decides what evidence a jury can use for its decision.

If lawyers can’t settle a dispute, the case goes to trial. The suing party, presents evidence first. Then the sued party, can present evidence. Usually, the plaintiff also has a chance to rebut the other side’s evidence afterward.

Here are some examples of logic and reasoning in legal cases.

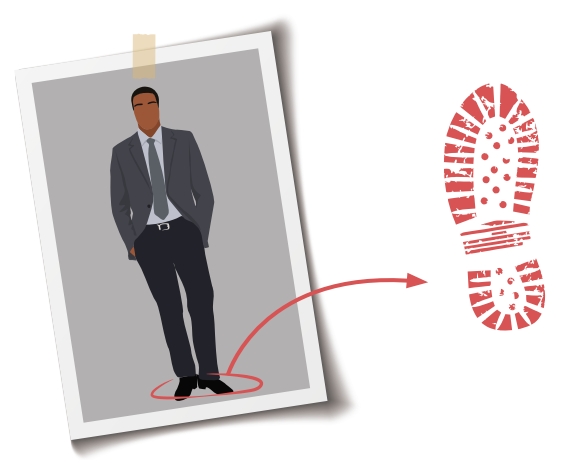

A bloody shoeprint

A good example is the wrongful death case against Orenthal Simpson, a former US football player. In 1994, Simpson’s ex-wife and a man were killed at her home. Police charged Simpson with the murders, but a jury found Simpson not guilty of the crimes in 1995. (“Not guilty” does not mean someone was innocent. It just means the government didn’t prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt.)

Then family members of the murdered people sued Simpson for money. In that case, the families only had to prove their case by a preponderance of the evidence. That means showing it was more likely than not that their claims were true.

As it happened, police had found a bloody shoeprint at the murder scene. The bloody shoeprint was the right size for Simpson. Few pairs of the expensive shoes were sold. One seller was a shop Simpson had gone to.

The plaintiffs’ lawyer, Daniel Petrocelli, asked Simpson if he had ever bought a pair of the shoes.

“No,” Simpson answered. He knew those shoes were involved in the case. But he added, “I would have never worn those ugly … shoes. ”

“ Why? ”Petrocelli asked.

Simpson answered that, “to me, they were ugly shoes. ”

Then Petrocelli showed a photo of Simpson in similar shoes and asked about it.

“It appears to be me, yes,” Simpson said. He still tried to say he didn’t own the shoes, but the damage was done.

Deductive reasoning let the jury conclude Simpson was not telling the truth about everything. He said he would never wear the shoes. But he obviously had worn the shoes.

And inductive reasoning could let the jury find that Simpson had killed his ex-wife and the other person. The killer likely left the bloody shoeprint at the crime scene. The shoe that made the print was a style Simpson had worn. And there were few pairs sold. It wasn’t impossible for someone else to have left the shoeprint. But all the facts suggested that he was the one who left the bloody shoeprint and committed the murders.

The jury found Simpson liable, and he had to pay $33.5 million to the victims’ families.

A bank’s mistake

People aren’t automatically liable for all harms someone might suffer. As British judge Patrick Devlin wrote in a 1963 case, “No system of law can be workable if it has not got logic at the root of it.”

In that case, an advertising agency asked a bank about the creditworthiness of another company. The bank mistakenly said the company’s credit was good. The advertising agency accepted the company as a client and bought ads for the company. The company then failed to pay the advertising agency for the ads. The advertising agency sued the bank.

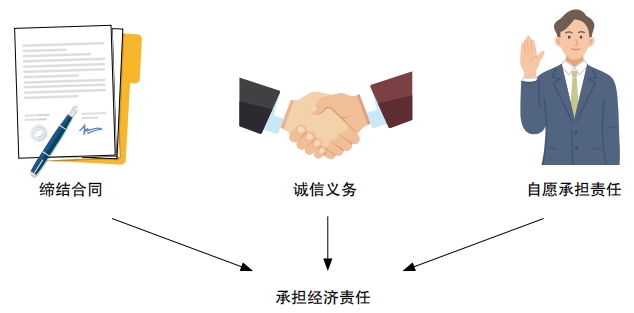

Judge Devlin’s opinion used deductive reasoning with the following premises and conclusion:

A bank can only be liable for another party’s economic loss resulting from its inaccurate statements if it owed a duty to the other party. And in order for that duty to exist, there had to be a “relationship equivalent to a contract. ”

In the advertising agency case, there was no such relationship.

A. The bank did not have a contract with the advertising agency.

B. Nor was there a fiduciary duty—a legal relationship requiring it to act in the other party’s interest.

C. Nor did the bank volunteer to take on a duty toward the advertising agency. The bank’s letter said it was for the advertising agency’s “private use and without responsibility on the part of this Bank. ” Furthermore, “A man cannot be said voluntarily to be undertaking a responsibility if at the very moment when he is said to be accepting it he declares that in fact he is not,” the judge wrote.

Therefore the bank did not owe anything to the advertising agency, Judge Devlin concluded. Other judges in the case also decided that the bank was not liable.

A criminal corruption case

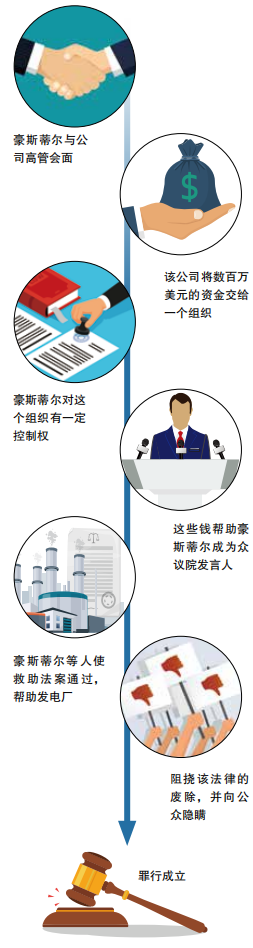

A 2023 US district court case shows how a jury can use inductive reasoning to determine facts that show guilt. The government charged former Ohio state government official Larry Householder and others with a crime under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO. Atrial for two of the five defendants took place in early 2023.

The government claimed Larry Householder and others were part of a criminal enterprise in which an electric utility company paid millions of dollars in bribes. In return, the court filing said, the defendants used the money to help pass and protect a law to make ratepayers pay more than $1 billion for non-competitive power plants.

There was no written agreement. Nor did witnesses testify that they specifically heard the defendants make that agreement. And the US Constitution says the government can’t force people to testify against themselves.

However, there was a lot of circumstantial evidence. That’s indirect evidence that is consistent with a claim. In this case, documents showed that company executives met with Householder. Shortly after that, the company arranged for millions of dollars to go to an organization. Other evidence showed that Householder exercised some control over that organization. The money helped Householder become speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives. The money benefitted the defendant and others in other ways too. Still more evidence showed how Householder and others acted to pass a bailout law to help the power plants. Then Householder and others worked to block an effort to get ride of the law. And the defendants and others worked to hide what their actions from the public.

All of that evidence showed the crime took place. And there wasn’t another reasonable explanation, the government argued.

“You determine all of that based on your common sense,”prosecution lawyer Matthew Singer told jurors in his closing argument. He urged them to draw inferences from “the timing, the witnesses, the evidence. ” In other words, he wanted them to use inductive reasoning to find that all the evidence, added together, showed guilt.

Singer’s closing argument also blunted an expected argument for the public official. On the stand, Householder had said he wasn’t at a dinner where the plot was supposedly hatched. But then the government showed a photo contradicting his statement. “He did not tell the truth,” Singer told the jurors.

The jury found the two defendants guilty in March 2023. Lawyers for the two defendants will likely appeal the verdict. Appeals courts usually uphold case verdicts unless the trial court made a mistake of law.

Unfair interrogation

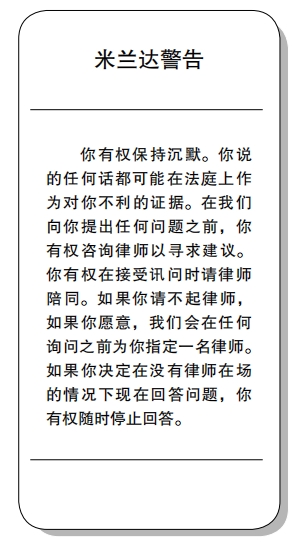

Even if evidence tends to show guilt, defense lawyers can argue that the jury shouldn’t see it. In a 1966 case in the United States, for example, the police took Ernesto Miranda into custody. They did not warn Miranda about his right to have a lawyer present during questioning. Miranda confessed to the crime.

On appeal, the US Supreme Court found the failure to give the warning meant his confession should not have been allowed to be presented to the jury. The court reversed the conviction:

Under the US Constitution, “the individual may not be compelled to incriminate himself,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in the majority opinion.

Compulsion is “inherent in custodial surroundings” unless there are protections, like having a lawyer present, Warren continued.

People have a right to have a lawyer present during questioning when they’re in custody. But they can’t exercise that right if they don’t know about it.

Unless police warn people, they can unfairly take advantage of defendants who don’t know their rights.

“Miranda was not in any way apprised of his right to consult with an attorney and to have one present during the interrogation,” Warren wrote.

Miranda’s confession should not have been used as evidence.

That might not seem logical if the evidence shows that someone was guilty. But keeping the evidence out protects the rule of law. It guarantees “judicial integrity so necessary in the true administration of justice,” Justice Thomas Clark wrote in a 1964 case, Mapp v. Ohio. If there are no consequences for violating someone’s rights, a government may violate more people’s rights. And if people see the government as acting unfairly, they won’t respect the government or its laws. So, because the goal is to have people respect the rule of law, courts must make sure people’s rights are protected—even if some criminal defendants go free.

Overruling an earlier case

Lawyers face extra challenges if they want courts go against a prior (same case) decision. They must argue the justice of their case. And they must also show why the court should not follow the prior case but instead overrule it.

One example is a 1954 US Supreme Court case known as Brown v. Board of Education. An 1896 case about railroads had said discrimination based on people’s race was lawful if there were separate but equal facilities for each group. In the 1954 case, a Kansas city’s schools for Black children and its schools for White children had similar physical facilities. So, the city argued, there was no problem.

Lawyers for the Black children had experts testify at the trial court level that segregation itself hurt Black children’s ability to learn and develop. That meant there could not be “separate but equal” schools, they argued. Their case was like earlier cases about graduate and professional schools.

“In this case we have positive testimony… that the humiliation that these children have been going through is the type of injury to the minds that will be permanent as long as they are in segregated schools,” said lawyer Thurgood Marshall during oral argument. “Not theoretical injury, but actual injury.”

Moreover, Marshall said, the main authority relied on in the 1896 case was decided before the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution became effective in 1868. That amendment says states must provide “equal protection of the laws.” But that could not happen when children felt the impacts of segregation. “On a classification basis, these statutes were bad,” Marshall said.

Marshall also argued that the segregation laws perpetuated “the badge of slavery” by treating Black children differently. “Racial distinctions in and of themselves are invidious,” Marshall said. Invidious means offensive and unfair.

On appeal, the United States Supreme Court agreed and overruled the earlier case. “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote. “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Of course, judges aren’t perfect. Sometimes their reasoning is faulty. Or implicit biases may shade how they weigh arguments. If there are no further appeals, parties in a specific case may then just have to deal with the consequences.

Or people may use reasoning to push for better laws to correct a problem. After court rulings upheld some state statutes making it harder to vote, for example, groups pushed for a federal law to block those statutes. Lawyers also can look for cases with similar themes but rely on different facts where other arguments might succeed.