In November 2014, LeeAnne Walters turned on the tap in her kitchen in the city of Flint, Michigan. Disgusting, brown water streamed out. Over the following weeks, its color ranged from “light yellow to nasty, dark-looking

cooking grease,” she recalls.

For many months before the water changed color, she, her husband, and her four children had been suffering from mysterious health problems. Their hair fell out in clumps in the shower. LeeAnne lost her eyelashes. When her three-year-old twins took baths, they broke out in rashes. Her fourteen-yearold son got such terrible abdominal pains that she took him to the hospital. What was going on?

When LeeAnne saw that brown water, she asked the city to test it. Finally, in February of 2015, they did. LeeAnne says, “I got a frantic phone call from the water department telling me not to drink it, not to let the kids drink it, not to mix my kids’ juice with it,” LeeAnne told reporters. The water contained lead, a poison that is especially harmful to kids. There was so much lead that the water was equivalent to toxic waste. Whenever LeeAnne and her family and neighbors drank this water, used it for cooking, or bathed in it, they were poisoning themselves.

Rivers and Lakes

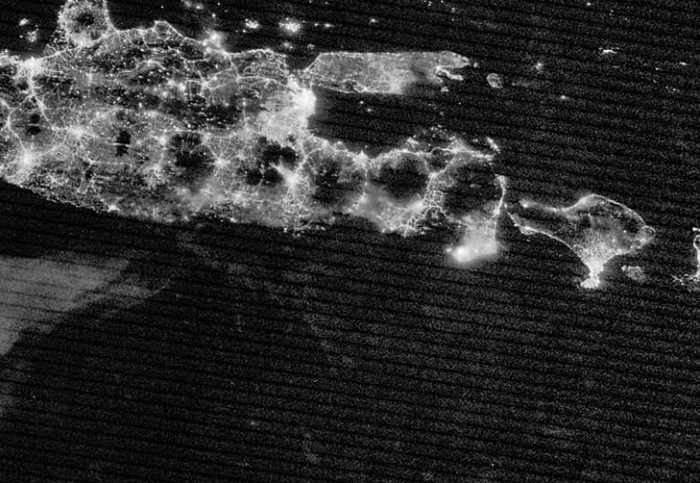

Access to freshwater depends on geography. For cities or towns without lakes and rivers nearby, clean, fresh water may be very hard to get. That’s not at all the case in Flint, Michigan. Fresh water is abundant. “We are surrounded by the Great Lakes. And the Great Lakes happen to be the largest source of fresh water in the world,” says Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Michigan State University who treats patients in Flint, Michigan.

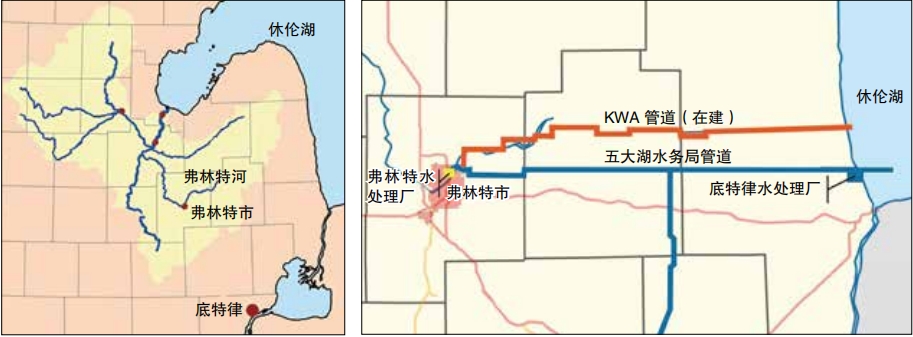

For almost fifty years, Flint had gotten its water from one of the Great Lakes, Lake Huron. The city of Detroit has a water treatment plant that cleans this lake water to make it safe to drink. Next, Detroit pipes the clean water out to nearby areas. Flint had been paying Detroit to tap into this clean water source.

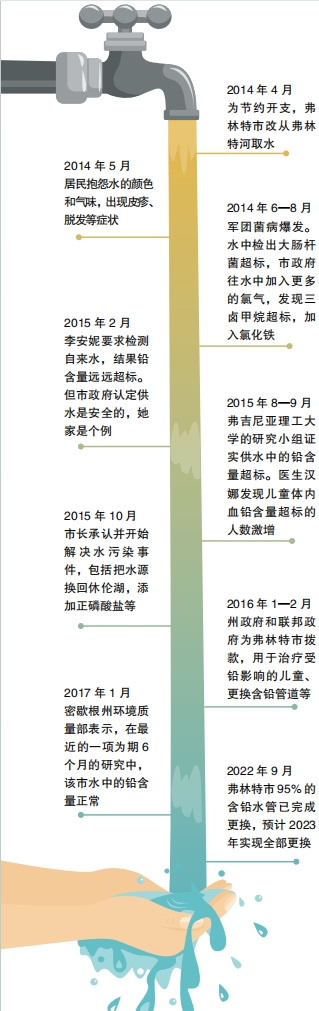

Unfortunately, Flint was out of money. So the state put an emergency manager in charge of the city’s budget. This manager and a team of officials decided to save money by getting the city’s water elsewhere. The plan was to build a direct pipeline from Lake Huron to Flint. But that pipeline wouldn’t be ready for a few years. So the officials made a fateful decision to switch the city’s water source to the Flint River. The change happened in April 2014.

A Filthy River

When the city announced that it would get its water from the river, residents were shocked. “We thought it was a joke,” Rhonda Kelso of Flint told CNN in 2016. The Flint River was notoriously filthy thanks to many decades of pollution. “That river has been an industrial dumping ground for 75-plus years,” said LeeAnne.

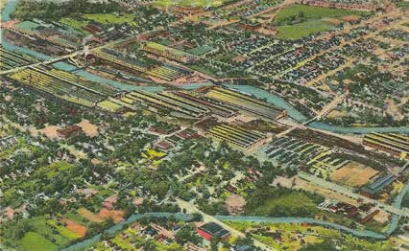

Flint hadn’t always been poor. Once, it was a thriving industrial city. At first, the city processed lumber, paper, and chemicals. Later, it hosted factories that built carriages and then cars. For most of the twentieth century, Flint was the home base of General Motors, one of the largest car companies in the world.

All of these industries dumped their waste directly into the Flint River. Before 1955, the city also got its drinking water from the river. This wasn’t unusual. Back in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, no one worried much about water pollution. The natural world is so vast that contaminants rapidly spread out and seemed to disappear. Also, it’s possible to treat even very dirty water to make it drinkable. Starting in the 1900s, Flint filtered and chemically treated its river water. The city built a new water treatment plant in 1954.

However, the industrial revolution introduced huge amounts of contamination into the air, water, soil, and rest of the environment. All of this pollution built up over time until people could no longer ignore it. In the 1930s, huge numbers of fish in the Flint River started dying. In 1936, The Cuyahoga River in nearby Cleveland, Ohio, caught fire. Oil and debris floating on its surface fueled the flames. Rumors say that the Flint River caught fire several times during this same period as well.

As the river grew more and more polluted, the city of Flint got bigger and bigger. City officials knew that river pollution was a problem. But the main reason they started buying water from Detroit was to support a growing population. They didn’t think the Flint River was big enough to support their factories and citizens. The water the city got from Detroit was already treated. So Flint’s water treatment plant stopped running regularly. A few times a year, it would treat river water to remove pollution, then discharge the water right back into the river.

Factories weren’t the only things polluting Flint River. Wastewater from people’s homes also found its way into the water, promoting the growth of harmful bacteria. Fertilizers from farms located far upstream led to algae growth that turned the water cloudy and brown. Landfills full of people’s trash leaked chemicals into the ground, groundwater, and river. Rock salt from bridges crossing the river would also fall into the water, making it more corrosive.

Cleaning up the Mess

In the middle of the twentieth century, brand new environmental laws stopped US cities and companies from dumping chemicals, wastewater, or sewage directly into rivers. The Clean Water Act of 1972 was an especially important law. However, preventing most of the major sources of pollution wasn’t enough to fix the problem of water pollution. Most contaminants dissolve easily in water, which makes them difficult to remove.

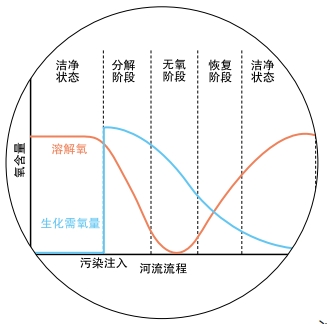

As cleaner water flows into a polluted lake or river, contaminants will eventually wash away. The time it takes for a substance that’s entered a body of water to leave naturally is called the retention time. The Great Lakes are large and have very long retention times. Lake Huron’s is 22 years and Lake Superior’s is 191 years. Most rivers have a much shorter retention time of about a few weeks.

Though this helped make the Flint River cleaner over time, it hasn’t been possible to completely stop all sources of pollution.

In 1977, the water pipeline leading from Detroit cracked. While it was getting fixed, the city temporarily switched to the Flint River as a water source. Reports about the situation said that it took “10 times the amount of chemicals to treat Flint River water than Lake Huron.” Also, illegal dumping and accidents still happened sometimes. One of the worst incidents happened in 1999, when a worker digging a trench accidentally broke open a city sewage pipe. Over the course of two days, twenty-two million gallons of waste gushed into Flint River. For a little over two years, no one was allowed to swim or fish in the river.

Lead in the Pipes

Despite this long history of pollution, the officials in charge of Flint in 2013 and 2014 thought that the city’s water treatment plant would be able to make the water safe enough to drink. This plant hadn’t operated at its full capacity in decades. It was old and in disrepair. Just before the switch was made, Mike Glasgow, a water quality supervisor at the plant, sent an email stating, “I do not anticipate giving the OK to begin sending water out anytime soon. If water is distributed from this plant in the next couple weeks, it will be against my direction.”

The city switched over anyway. LeeAnne and her family weren’t the only ones to notice a big difference. Within a few weeks of the switch, many residents noticed an odd color, foul smell, or bad odor in their water. Officials promised the water was clean, but locals didn’t believe it. “I don’t know how it can be clean if it smells and tastes bad,” Senegal Williams told reporters in June 2014. Some people started buying bottled water. Sadly, many Flint residents lived below the poverty line and couldn’t afford this extra expense.

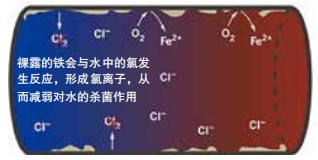

The first major health problem to strike residents was an outbreak of Legionnaire’s disease, a deadly form of bacterial pneumonia. The illness killed twelve people and made eighty- seven more sick between June 2014 and October 2015. High levels of bacteria in the water likely caused this outbreak. So the city added extra chlorine to the water to kill microbes. Meanwhile, LeeAnne’s family and many other residents who relied on Flint’s tap water experienced rashes, hair loss, and other disturbing signs that something was very wrong. The unusual smells and icky colors of Flint’s water were caused by other issues, such as iron corroding off the pipes. That iron bonded with chlorine and reduced its ability to kill germs. So the water also had high bacteria levels, which have caused the rashes and some of the other health issues.

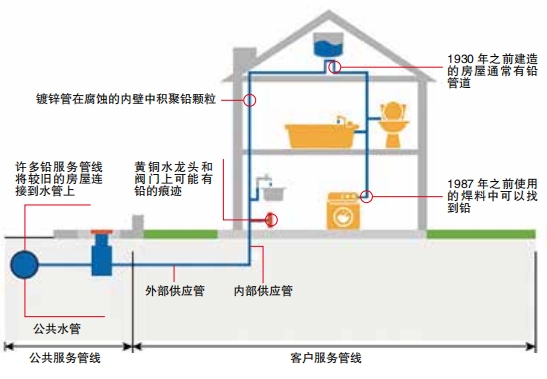

It turned out that the officials in charge of treating the Flint River water had skipped a very important and required step. They weren’t adding any corrosion control to the water. This was illegal and very dangerous, especially since Flint’s water pipes were made of lead. We know now that lead is a dangerous poison, but back in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people only knew that lead didn’t rust or decay as easily as other metals. It made long-lasting, durable pipes. Today, many cities and towns still rely on systems of lead pipes built a long time ago.

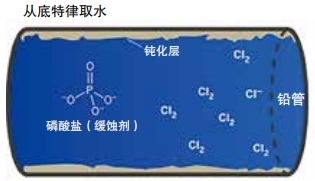

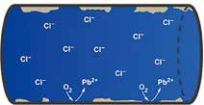

When the water treated in Detroit flowed through Flint’s lead pipes, there were no problems since the water wasn’t corrosive. Detroit used corrosion controls. For example, chemical compounds called orthophosphates react with lead to make a coating that corrosive water can’t eat through. So the lead in the walls of the pipes stays put. Tragically, Flint’s water treatment plant failed to add these important compounds.

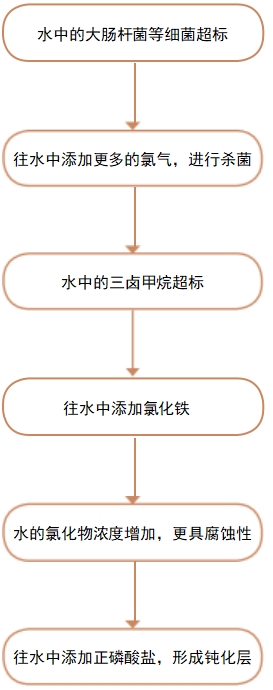

Flint River water was corrosive already, mainly due to road salt that had entered the river. In addition, all the extra chlorine that had been added to control bacteria reacted with organic matter in the water to create high levels of toxins called trihalomethanes. To deal with these toxins, the water treatment plant added ferric chloride. This chemical made the water even more corrosive than it already had been.

When this water started flowing through Flint’s lead pipes, the metals in the walls of the pipes began to break down and enter the water.

Lead is impossible to see, smell, or taste in drinking water. However, lead contamination was the most dangerous thing in the water, especially for children. Lead slows a child’s growth and brain development, causing learning and behavior problems. These problems can’t be reversed. “[Lead] can alter the entire life trajectory of not just one child, but an entire population of children,” said Dr. Hanna-Attisha. A child exposed even to very small amounts of lead is more likely to have a lower IQ or to develop ADHD. Some studies have linked childhood lead exposure to increases in violent crimes as these children grow up. In Flint, an estimated nine thousand kids under the age of six were exposed to high lead levels. Sadly, one of LeeAnne’s children was diagnosed with lead poisoning.

Making Their Voices Heard

In February 2015, the city knew that LeeAnne’ water was badly contaminated with lead. But officials insisted the problem was only in her home. That was ridiculous since her home didn’t contain any lead in its plumbing. “It was very obvious that we were being lied to,” LeeAnne said. So she decided to do something about it.LeeAnne, a stay-at-home mom, taught herself about water chemistry. She teamed up with Marc Edwards, an environmental engineer at Virginia Tech. When he tested thirty different samples of water from the LeeAnne’ home, the lowest amount of lead he found was three hundred parts per billion, the average was two thousand parts per billion, and the highest was more than thirteen thousand parts per billion.

Together, LeeAnne and Edwards created a plan to scientifically test Flint’s water. LeeAnne and a team of locals distributed test kits to people all around the city. They collected eight hundred water samples and then sent them to Edwards for testing. Sure enough, the results showed shockingly high lead levels. No level of lead in water is safe, but the EPA requires action at a level of fifteen parts per billion. Edwards found that the water in one out of every six homes exceeded this level. The team announced their results in September 2015.

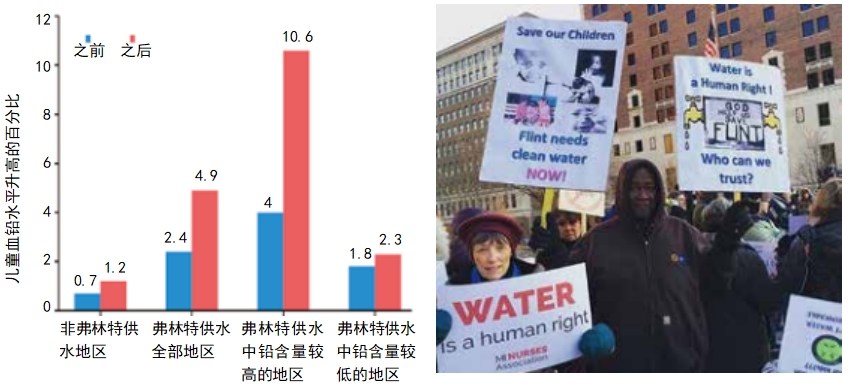

That same month, Dr. Hanna-Attisha announced the results of her own research. All around the United States, children are regularly screened for lead as part of their regular check-ups. She looked at Flint’s data and discovered that lead levels in kids exposed to the bad water had doubled since the city had switched water sources.The areas of the city with bad water had a higher population of African American and low-income families. Outside these areas, 24% percent of children are African American, while that percentage was 77 percent in the part of the city that had bad water. This wasn’t just an issue of pollution – it was also racial injustice.

After these scientific investigations, officials could no longer deny what was happening. Flint was in the midst of one of the biggest environmental crises ever to happen in the United States. The city switched back to Detroit’s Lake Huron water. However, the badly damaged lead pipes were still a big problem. So the city began distributing bottled water to residents for free. In the years since the crisis began, the city has been replacing all of its lead pipes. This project is supposed to be completed in 2023. At that point, finally, Flint’s residents will be able to trust that their water is safe.

Sadly, what happened in Flint, Michigan has happened all over the world. People have accidentally or knowingly allowed pollution or contamination to reach water, air, and soil. Air pollution is especially common and harmful. Exhaust from vehicles and factories as well as forest fires puts harmful particles and gases into the air. These pollutants can cause serious health issues. Soil pollution can be very difficult to notice or test for, but also causes serious problems. Lead and other poisons, such as arsenic and cadmium can travel from soil into crops. Pollutants from plastics and medicines often end up in water or soil, where they cause health effects that aren’t yet fully understood.

When an important part of an area’s geography becomes polluted, people suffer. Often, those who suffer most come from the poorest, most marginalized communities. They have fewer options for where to live or where to get their water or food. So they may end up drinking or washing with polluted water, breathing polluted air, or growing food in polluted soil. This shouldn’t happen in the first place. But when it does, those with money and power should step up to change things. Among the many lessons Flint teaches is this important one: When people speak up about a problem, officials should listen and act.