As you’re learning, there are many amazing techniques available to modern archaeologists. These involve detailed study of small areas of ground, but how do people know where to start looking in the first place?

Find the right site

Sometimes archaeologists find a place by accident. Many modern cities have literally built up over time—new buildings are built on top of the remains of older ones, which means there are thick layers full of archaeological remains. In many countries, builders digging deep to make tunnels or foundations are required by law to report anything they find. Archaeologists then come and quickly study the site before letting building continue. A recent engineering project, called CrossRail, in London discovered ten thousand objects from over forty sites, ranging from prehistoric to nineteenth century in age.

This isn’t just a modern thing. The Roman remains in Herculaneum and Pompeii were both discovered in the eighteenth century by people digging holes for buildings.

In some countries, people use metal detectors to search for ancient objects. These devices can spot buried metal and did find somethings, like bags full of beautiful items made of gold and precious gems . These were buried for safekeeping centuries ago, but the person who did this never came back. According to laws, such treasures should be placed in a museum, but sometimes people sell them in secret. For this reason, private use of metal detectors on ancient objects is prohibited in many countries including China.

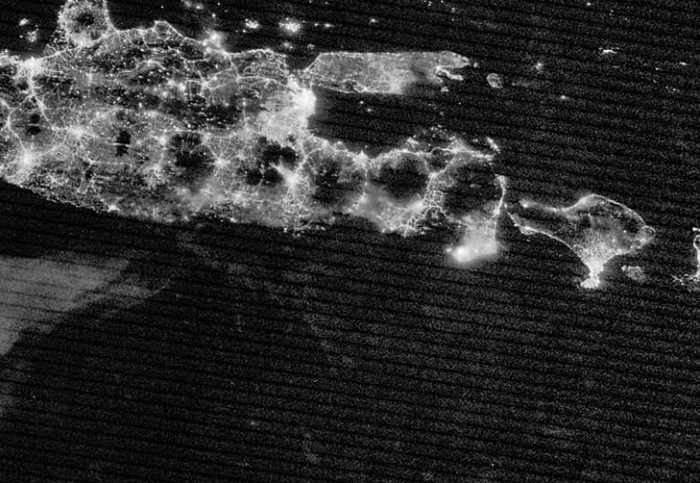

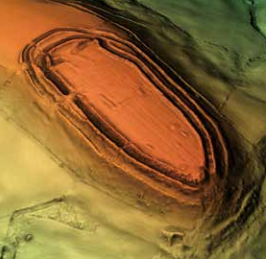

Modern techniques to find archaeological sites include the use of satellites, aircrafts, or drones to detect the potential sites and collect data. The analysis of the data helps archaeologists to discover the location of ancient sites. These are particularly useful in remote areas. Photographs taken from satellites or aircraft allow studies to be made in desert areas . Structures made by humans can be spotted this way, such as the Nazca Lines in Peru. They were created between 500 BC and AD 500 in the desert and some lines form huge images of plants or animals. Archaeologists believe that there are more figures to be found. They became famous in 1939, thanks to the American scientist Paul Kosok, who during a plane flight was able to reveal the scale and shape of the works.

In dry weather, the vegetation above a buried feature such as a wall may grow more slowly due to poor drainage. This makes patterns in the crops or soil that can be spotted from above. LiDAR is a technique that uses lasers to scan objects in great detail. Surveys done from aircraft allow extremely accurate measurements of topography, with precision of less than a meter. The structure like wall remains, ancient roads, or ditches can be easily spotted this way. The technique is able to distinguish between soil and plant material, allowing it to “see through” trees and vegetation. LiDAR surveys of jungle areas on many continents have rediscovered ancient cities hidden under deep vegetation.

Searching for burial goods

Many wonderful things can be found in ancient burial places. These may be in large impressive structures (such as the Pyramids in Egypt) or on mounds built on hilltops. Archaeologists dig into these structures, but sometimes they find someone has been there before and stolen anything of value . This is a tragedy not just because the valuable things should be in a museum open to the public, but also because the information about the past that could be learned from those objects is lost. Archaeologists do more than dig up old objects. They carefully record the location of each object, particularly tracing which geological layers it came from. Every object is kept and recorded. As every year more and more techniques are invented and applied in findings, even the most ordinary object can be interpreted deeply and provide information.

At first , let’s look at how archaeological sites get created and why tracking layers of soil is important.

Stratigraphy in archaeology

Think of an old -fashioned archaeology professor with an untidy desk. Everyday, he reads a lot of different pieces of paper. Some of it gets piled up on his desk, more and more each day. If your task is to introduce the professor as much as possible by analysing the pile of papers, what would you do?

I hope you wouldn’t just dig into the pile and look for interesting things. You’d miss so much information! Think about how the pile of papers changed over time. Things nearer the bottom were read first with later paper placed on top. If you keep a note of where they are in the pile, you could tell in what order they were read. If there are newspapers in the pile, you can tell when a particular thing was read. A page above a newspaper from a particular day was placed there after that day.

If sometimes the professor ate at his desk, he could have left crumbs of food, you could workout what he ate and whether their diet changed over time.

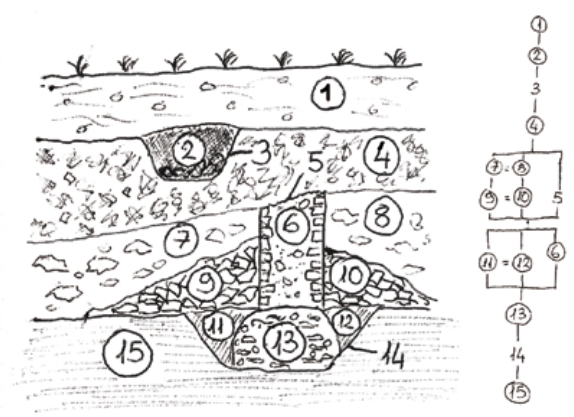

What I’ve described is how a modern archaeologist approaches a site. Instead of layers of paper, there are layers of soil or other debris that piled up over time. The same logic applies: the deeper a layer, the older it is, so we know the relative age of different layers.

Always be careful to spot where someone has dug a hole—things at the same level may be much younger. The edge of the hole will cut across the older layers and is usually a different material.

There are expensive houses being built in London with big basements . It’s cheaper to leave the excavator buried under the bottom of the cellar than to pull it out again. Imagine an archeologist in the far future digging into London . If they don’t spot that the basement was a hole dug into the older layers, they might think that the digging machine was hundreds of years older than it actually is.

The study of geological layers, or strata, is known as stratigraphy and is also used by geologists on sedimentary rocks or even to study features on Mars. Now, let’s look at some examples of how the archaeologists have found sites and used stratigraphy to tell us about the past.

The lost city of Troy

The works of Homer are one of the foundations of European culture. Written nearly three thousand years ago, they are stories of angry gods, terrifying monsters, brave heroes, great battles, and the siege of a city called Troy. The stories are still famous today, but in the nineteenth century they were even more so and were studied in the original Greek by every well-educated European. Many recognizable Greek cities are mentioned by Homer. It was only natural to speculate about whether the stories about Troy were based on events in a real place, an ancient city since lost.

Heinrich Schliemann was a rich German businessman who worked as an amateur archaeologist. He was particularly interested in finding sites mentioned in Homer and claims to have decided at the age of seven that he would one day excavate the lost city of Troy. He was active in the 1860s and 1870s, a time when modern scientific archaeological techniques were being developed.

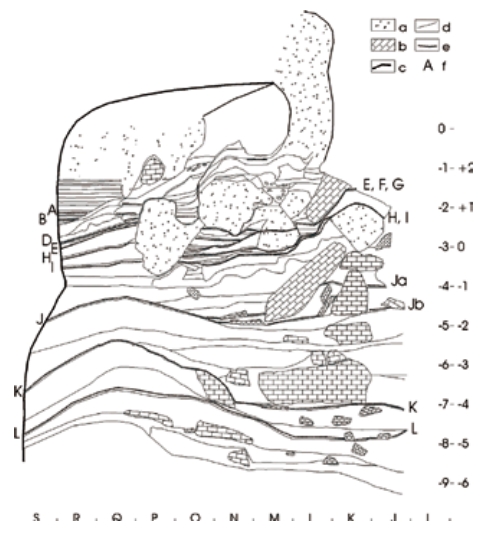

Schliemann started, like many others, by trying to match geographical features mentioned in Homer with the modern world. These suggested Troy was located in the northwest corner of modern Turkey, across the sea from Greece. He settled on a place now known as Hisarlik, a site on a hill that clearly contained archaeological remains, as a candidate. He dug an enormous trench down through the middle of the city. He took note of the different layers, which he numbered from one to nine. In layer two, close to the bottom, he found evidence for deliberate destruction of buildings and also a cache of gold and other precious objects. He decided that this layer represented the historic city of Troy and called the gold “Priam’s Treasure” after the king of Troy in Homer’s works. Schliemann gained much publicity, sharing photos of his wife wearing the treasure, which he smuggled out of the country.

Schliemann helped popularize archaeology and used the principles of stratigraphy, but he was also prone to making things up. His work was not up to modern standards. Having decided that layer two was from the time of Homer, he further excavated it, throwing away material from the layers above.

Later studies, able to use modern dating techniques, suggest that layer two is almost one thousand years too old to be the city described by Homer. Layers three to five are much better candidates, but ironically, much of the evidence here was destroyed by Schliemann, who dug them out without properly documenting what was there. The contents of the layers still exist but all jumbled up in piles of waste, making it impossible to say much about their history.

Modern archaeologists have discovered much more than Schliemann. They realized Schliemann’s nine layers are actually twenty-two thinner ones and learned about the different people who lived there for over 3500 years. There is still debate over whether this was the city that Homer wrote about. For sure, it was the site of battles in the past, but it may never be possible to be certain this was Troy.

Digging an ancient home

Archaeology isn’t just about finding treasure and palaces. It’s also a way of recreating the details of the past to understand their day-to-day activities. The depiction of early humans in popular cu lture shows the m as unintelligent cavemen, very different from us. However, modern scientists challenge this view by showing the sophisticated ways in which they lived their lives.

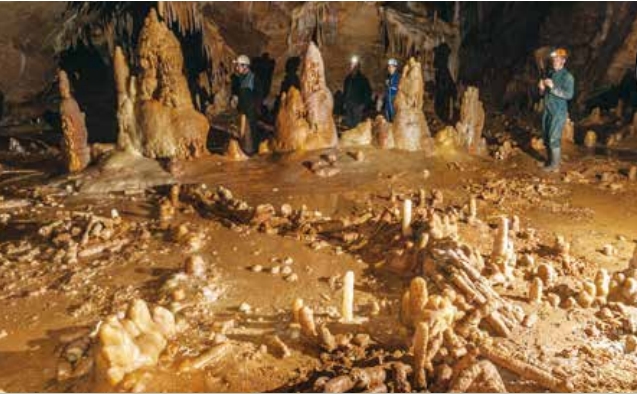

Neanderthals are a form of ancient human that lived in Europe from around two hundred fifty thousand to forty thousand years ago. Much of what we know about them comes from caves. They regularly used these as shelters as they moved around hunting large animals. Deposits from a cave called Abric Romani in Spain have been used to reconstruct their lives in great detail.

In this cave, the sequence of sedimentary layers sits under a rock shelter and is over twenty meters thick and formed between seventy and forty thousand years ago . It shows occupation by Neanderthal people for thousands of years. What is remarkable is that it consists of thin layers containing archaeological traces separated by layers of rock called tufa that form on the floor. This allows the archaeologists to separate out thin layers over a large floor area (over 200 m2) . By recording every item found in each layer very precisely, they can reconstruct how people lived there.

A single layer may represent one visit to the area. Neanderthals travelled widely, hunting herds of large animals that themselves moved around. Each layer might contain traces of soot and burnt material from one or more fires, bones and other remains from the animals they had caught, and fragments of stone. Ancient humans used stone in sophisticated ways, creating different types of tools, like arrow heads, scrapers, and spear points . By tracking each tiny piece of stone, archaeologists are able to piece them together into the original blocks. They can precisely show how a single block of stone was fractured into multiple types of tools and that old tools were sharpened and reused. They recreate the work of a single person working with the stone and leaving the unwanted pieces behind.

The same technique can be used for the study of bones. Neanderthals hunted large creatures—deer, wild horses, ancient cattle—and turning these into food required processing of the carcass. Different parts of the animals were processed in different areas of the cave, presumably by different people. One place was used to butcher the animal, another to break bones to extract its marrow.

Wooden tools have also been found at this site. All the evidence, creation of tools and organized processing of animals, shows their intelligence and similarity to modern humans. The evidence is vital to debates over whether they could use language or even if they should be regarded as human.