An old adage holds that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The saying refers to the subjective nature of beauty. What one person finds beautiful might not appeal to someone else.

Nonetheless, researchers have found common traits in scientific concepts that experts deem beautiful. And when it comes to what happens in the body, people’s experience of beauty isn’t in the eye, but in the brain.

The Big Picture vs. the Details

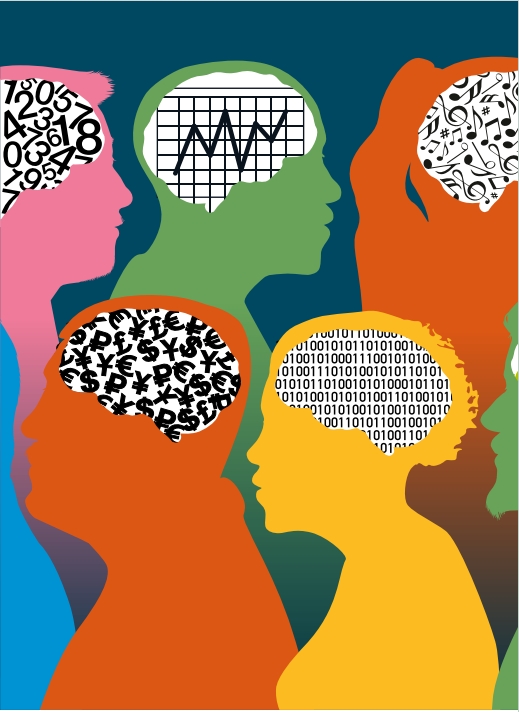

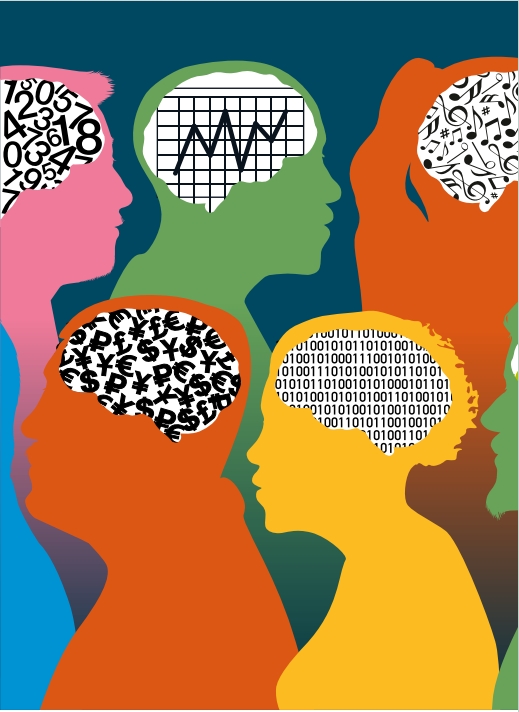

What scientists see as beautiful might depend on their field. Ben MacArthur is at the Turing Institute and University of Southampton in the United Kingdom. His work uses mathematical approaches to study issues in cellular and molecular biology. Writing in Nature Physics in February 2021, he described different ways that people in mathematics and physical sciences might see beauty when compared to biologists and other life scientists.

For example, “mathematics has a kind of clean, minimalist attraction. The best equations often have a simple form that belies the complexity of the phenomena they describe,” MacArthur tells Front Vision. “There is something very satisfying when things ‘fit together’ with no waste, and the best equations provide that. ”

“However, there is also real beauty in the extraordinary diversity and complexity of life,” MacArthur adds . “In this case it is to do with the extravagance of detail and the appreciation that these details are not waste!” As someone whose work deals with both math and life sciences, he says he “absolutely” sees beauty in both the big picture of elegant concepts that can explain many things and in the details that describe or explain diversity.

“I don’t think these two views are contradictory though,”MacArthur says. “The joy of an elegant theory is that it can explain extraordinary diversity, and do so simply. ”

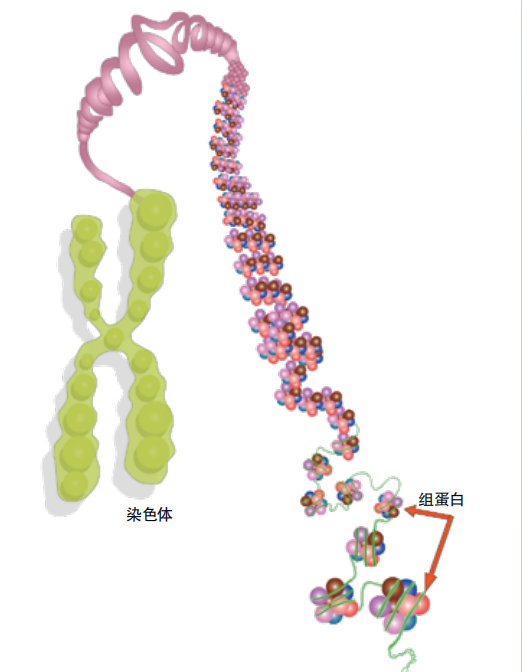

Neuroscientist Semir Zeki is at University College London in the United Kingdom . He doesn’t see a clear dichotomy about which types of scientists find beauty in elegant “big picture” concepts. DNA has long molecules that resemble a double helix, or a twisted ladder . Pairs of nucleotides along its length spell out the genetic code for humans and other living species.

The structure of DNA was shockingly beautiful because it was so simple,”Zeki says. “It really was the book of life written in two strands. ”

Similarly, Zeki says, the theory of evolution uses “a few simple lines” to explain diversity among species . As proposed by Darwin, species shared a common ancestor. Random mutations led to variations. And natural selection gave an advantage to mutations that helped organisms survive long enough to reproduce and pass traits on to offspring. In contrast, Zeki sees the complex species classification system developed by botanist Carl Linnaeus is “a sort of telephone directory. ”

The Brain at Work

“No theory of aesthetics is likely to be complete, let alone profound, unless it is based on an understanding of the workings of the brain,” Zeki wrote in Daedalus in 1998. For starters, the ability to appreciate visual art requires proper functioning of different aspects of vision. The eyes are the body’s sensory organs for vision. They transmit signals to various areas of the brain for interpretation.

So, sensing beauty in the color scheme of a painting can only be done if one can distinguish colors. Likewise, if an art piece incorporates motion, someone needs to be able to comprehend that things are moving. Different parts of the brain’s occipital lobe deal with those and other aspects of vision.

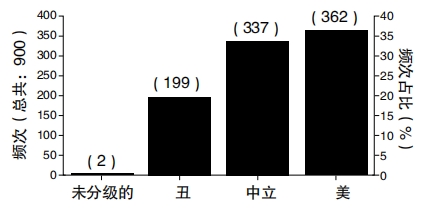

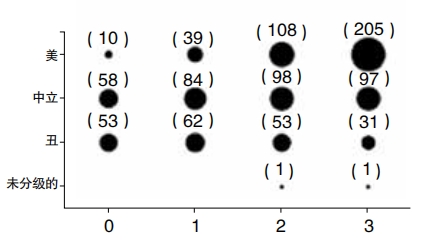

But beauty is more than perception. In a 2011 study, Zeki and Tomohiro Ishizu, also at University College London, asked people to rate works of visual art and music. People rated items on a scale ranging from ugly to beautiful. Based on those ratings, the team selected ten items from each category of ugly, indifferent and beautiful in visual art or music. Test subjects then listened to or looked at each item for sixteen seconds and indicated if it was ugly, indifferent or beautiful. As they did that,the researchers used scanners to see which parts of the test subjects’ brains were active.

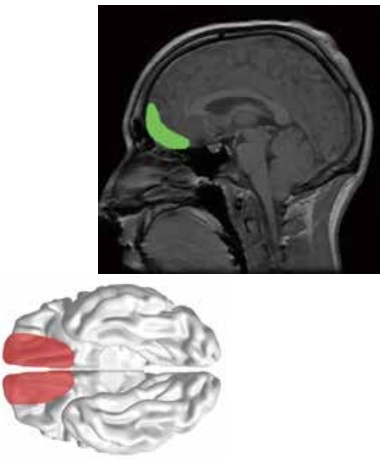

Multiple areas in the brain were active as people gave their ratings. Yet there was substantial overlap in the areas of activity when people rated either visual art or music as beautiful. Those areas were in part of the brain called the medial orbito-frontal cortex, or mOFC. It’s near the front of the head and above the eye sockets . Other studies had also identified the mOFC as a pleasure and reward center. Zeki and Ishizu reported their findings in PLOS One in 2011.

Beauty in Mathematics

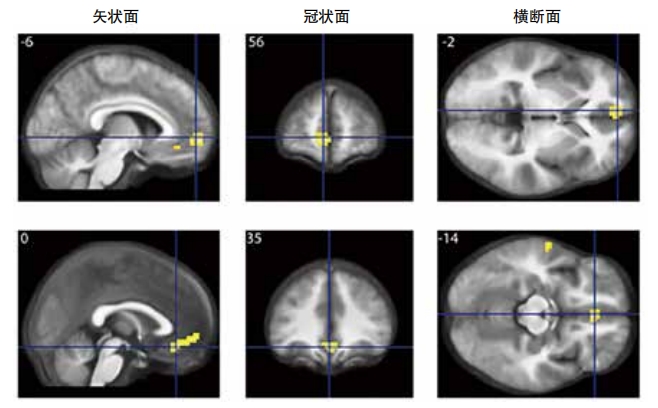

Zeki and others found that the beauty of various equations also sparks activity in parts of mathematicians’ brains that had been linked to people’s experience of beautiful visual art or music. The group had mathematicians rate sxity equations on a scale from the ugliest to the most beautiful. Two weeks later, the researchers scanned mathematicians’ brains as they again rated the equations’ beauty. In order to prevent fatigue, the mathematicians took breaks after each group of fifteen equations.

One equation that almost all the mathematicians had ranked as beautiful is Leonhard Euler’s identity equation: 1+eiπ =0.

It uses three basic arithmetic operations to link two irrational numbers— π (the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter) and e (Euler’s number, which is the base of the natural logarithm) with the imaginary number i (the square root of -1), 1 and 0. One of his coauthors on the paper “described it as the mathematica l eq u iva lent of the soliloquy in Shakespeare’s Hamlet,” Zeki notes.

As with the experience of visual art, Zeki’s group found areas of the brain’s m OFC were active when mathematicians rated equations that they deemed beautiful And that activity was related to how intense mathematicians said their experience of beauty was.

That result came as a surprise. “You could have had activity in the area of the brain that deals with mathematical calculations. You could have had activity in the areas that deal with visual information . But to have activity in the part of the brain which is always active when people experience beauty—and of course, when that activity is related in intensity to the declared intensity of the experience by the mathematicians—was not an expected thing,” Zeki says. The group shared its findings in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience in 2014.

The equations used in the study came from different branches of mathematics and physics. After the scans were done, participants rated how well they understood each equation. There was a good but imperfect correlation between their understanding and the beauty ratings given. The researchers analyzed separately the understanding and beauty effects in neural terms and then found that the activity in mOFC was specifically driven by beauty ratings, after accounting for the effects of understanding.

In a follow-up study, Zeki and University College London colleague John Paul Romaya teamed up with Oliver Chén at Yale University in the United States to dig deeper into the experience of mathematical beauty. They described this as biological beauty, which was “dictated by inherited brain concepts” and not likely to vary based on life experiences.

Zeki compares it to the way we can interpret people’s moods regardless of their culture. “If you see me smiling every day, you will perhaps deduce that I am a happy person. But so would everyone else in the world,” he says. “That is a very biological thing. ” Similarly, people in all cultures generally find beauty in nature.

In contrast, Zeki and his colleagues described artefactual beauty as something where people’s ratings depend more on their lived experiences. Those judgments also can be changed by people’s experiences.

“Offhand mathematical beauty really is the most extreme example of beauty which is derived based on language, learning and culture, because you’ve got to be a mathematician,” Zeki said. Yet when his team more closely examined the ratings of what equations mathematicians found beautiful, there was less variability than for ones that were rated neutral or ugly.

Toputitanotherway, theformulas rated most beautiful by the mathematicians had smaller standard deviations. The mathematicians’ rating of how well they understood the equations also was not significantly associated with the standard deviation of their beauty rating.

“We believe that at least part of the experienced beauty of a mathematical formulation lies in the fact that it adheres to the logical deductive system of the brain, which is similar in individuals of all races and cultures,”the team wrote. The group shared the study results in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience in 2018.

It’s unclear whether the brain scans other types of scientists rating beauty in science would likewise show areas that overlap with the areas that are active when people view visual art or listen to beautiful music. That research apparently hasn’t been done yet.

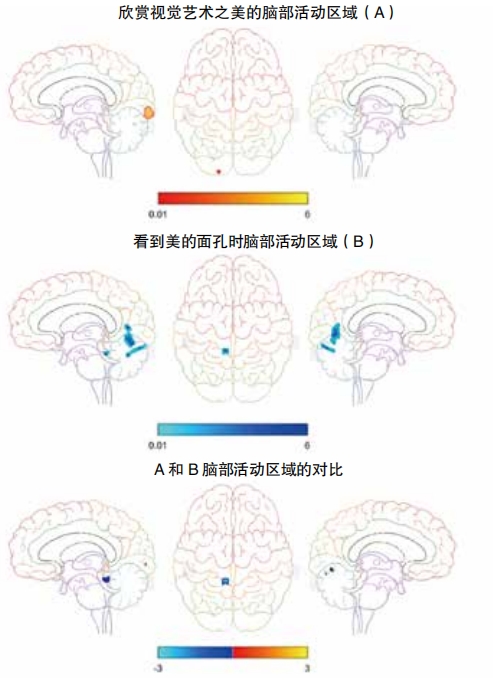

Also, although various researchers support the view that the brain has particular areas linked to beauty, some disagree. Recently, scientists at Tsinghua University in China worked with researchers in Scotland and Germany on a meta-analysis. They combined data from other studies. Some studies had brain scan data from when people viewed beautiful visual art. Other research had data for brain scans when people viewed faces they deemed beautiful. The team did not see significant overlap in the active brain areas.

The researchers shared their findings in the December 2020 issue of Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. Because the data came from multiple studies, though, it’s unclear whether other factors might have played roles.

Scientific inquiries will continue. And that’s a beautiful thing!