When Kea hi Seymour was 12 years old, he watched a television show about kangaroos . He learned that these animals store energy in the long, stretchy tendons attached to their huge feet. Hitting the ground stretches the tendon like a rubber band, storing the energy from the impact. When the animal lifts off, the energy gets released, like a snapping rubber band, giving an extra boost of speed and power.

Seymour was inspired. He wanted to run with amazing speed, too. In an article for Make, he wrote, “Ever since I was 12 years old, I’ve been dreaming of dropping into the African savanna and running with cheetahs.” But he didn’t just dream about this idea. He decided to build a mechanical device that would help people run faster.

What was his first step? “I started researching biology and nature,” he told the Hustle. As he researched, he made sketches of boots that he hoped could give human feet the power and speed of fast animals. Kangaroos and cheetahs weren’t the best sources of inspiration, though. They’re both fast, but a kangaroo hops and a cheetah runs on four legs.

An ostrich runs on two legs. It can reach speeds of up to forty-five miles per hour (seventy-two km/h). “I found out that the ostrich was the fastest bipedal animal and started looking into its physiology, how it moved,” he said. He’d found the right animal model, meaning an animal he could use for inspiration. Ostriches run on the tips of their toes, while humans run on flat feet. So Seymour designed boots with a heel bounce device that lift a person off the ground. A small, toe-like spot touches the ground. When it touches, a lever bends backward, pulling on a stretchy, tendon-like band attached to the top of the boot. When the toe lifts off, the stretched band releases, catapulting the boot (and the person wearing it) forward with extra speed and power.

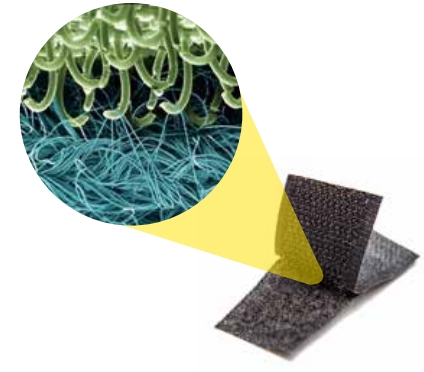

Seymour isn’t the only inventor who has looked to nature for inspiration. Biomimicry is the word for an engineering or design process that begins with a study of the natural world. One of the first examples of biomimicry in modern times happened in 1948, when the Swiss engineer George de Mestral returned from a walk with his dog and noticed hundreds of burrs caught on his clothing and in the dog’s fur. Burrs are small, spiky pods that plants send out to help spread their seeds . De Mestral looked at the burrs under a microscope and discovered that they were covered in hooks. De Mestral duplicated the hooks in a fabric fastener that he called Velcro . The invention process isn’t straightforward, though, even when the natural world offers an elegant solution. Engineers face many challenges and problems on the way from an idea to a working product. They must use ingenuity and perseverance to find solutions.

How to Run Like an Ostrich

While in high school, Seymour built his first prototype of what he calls Bionic Boots. A prototype is an early draft of an invention. He started with old rollerblade boots and attached metal struts for the lever and bungee cords for the stretchy band. When he tried them out for his class, he ran for a few strides, but then the contraption fell apart. “In those few strides, I could feel the power and speed. I knew I had something special,” he told the Hustle.

To make a prototype that didn’t fall apart, he needed better materials and a stronger design. He got another chance to work on his idea at Coventry University in the UK, where he studied transportation design. The new boots worked much better and even won a design award from the Royal Society for the Arts. Seymour used the money from the award to move to San Francisco, California and keep working on the boots. He set up a machine shop where he built all the parts of each new prototype by hand. He used drills, grinders, and hacksaws. He even had a carbon fiber oven in his bathroom. Carbon fiber is a polymer that is very light but strong.

Some of the ideas Seymour tried to improve the boots didn’t work. For example, in 2012, he tried making the main lever and toe out of carbon fiber . This made the boot much lighter. That’s good because a light material is easier to lift and push. But the material wasn’t strong enough to support his weight when he ran in the boots. So in future prototypes, he made these parts out of the same sort of very strong but light aluminum used in aircraft.

By 2015, the boot part of the Bionic Boots was made of carbonfiber. It had two aluminum levers, one for the toe and one for the main part of the boot. Multiple springs made of natural rubber connected the levers to the main boot. Adding springs makes the boot bouncier and stronger. A heavy person would need to use more springs than a light person to run at the same speed. Wearing the boots, Seymour could reach and maintain speeds of twenty-five miles per hour (forty km/h). The fastest human being on the planet, Usain Bolt, has reached twenty-seven miles per hour (forty- four km/h) during a sprint. But no one can keep up a speed like that for long without assistance.

Seymour wants to get even faster. His goal is to match the forty-five mile-per-hour speed of an ostrich. To do that, he plans to add battery-powered actuators. In robotics, actuators are the parts that convert electricity into force . These components could give the boots an extra boost beyond the force from the stretched springs. Seymour also hopes to 3D-print the boots out of titanium or carbon fiber. This type of manufacturing could reduce their weight since he wouldn’t need to use extra material to fasten different parts together.

Seymour has appeared on numerous television shows to demonstrate his invention. But initially, no company decided to fund and sell the boots. However, he finally started his own company to continue this dream. Maybe someday we’ll all have the opportunity to run with cheetahs and ostriches, thanks to biomimicry.

Cicadas’Wings

Biomimicry could also help save lives . When harmful bacteria form colonies on a surface, they may be impossible to remove completely, even with antibiotic drugs or strong cleaners. Colonies of bacteria can spread deadly infections. But what if colonies of germs couldn’t form on a surface in the first place?

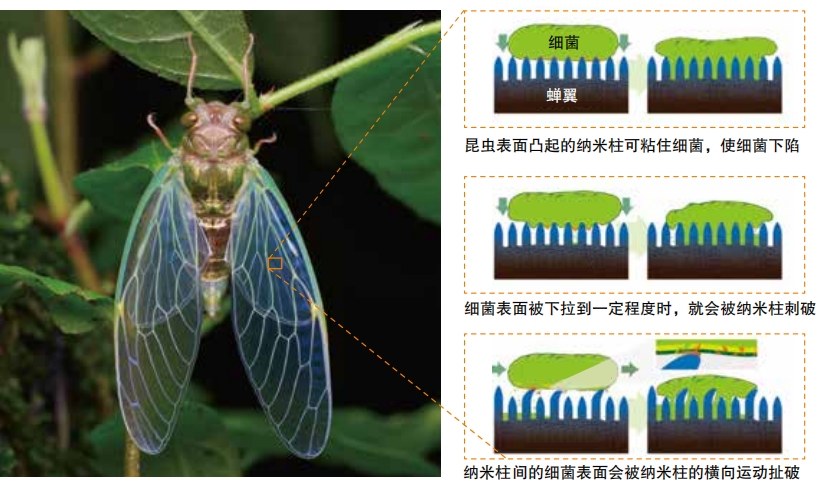

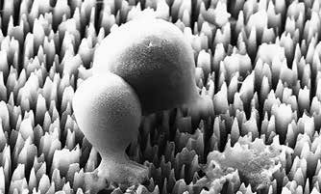

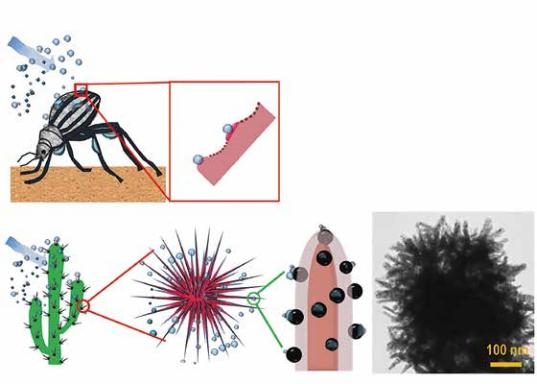

In 2012, Elena Ivanova and a team of biotechnology researchers at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia looked very closely at the wings of an insect called the C langer cicada and discovered something fascinating. The wings are covered with very tiny spikes, named nanopillars. These spikes tear apart most harmful bacteria, killing them and making it impossible for these germs to form a colony on the wing. (Some very rigid bacteria don’t get ripped apart by the spikes, but these bacteria tend not to harm living things .) The very structure of the wing’s surface is an antibiotic. Dragonflies have wings with similar structures.

Since this discovery, engineers and material scientists have been working to build nano pillars into manufactured surfaces. They know what these surfaces should look like, thanks to their close study of insect wings . And they can recreate very similar surfaces in the lab. In fact, researchers have made silicon, titanium, and polymers with the tiny spikes. And the materials successfully destroy germs.

Unfortunately, making these materials is very expensive. The nanopillars are so tiny that recreating them requires extremely precise tools and methods. “We can make these features with our ultraprecision engineering instruments, ” says Saurav Goel, an engineer at London South Bank University. But The real challenge will be scaling up the process so materials with the features can be produced reliably and affordably on a large scale.

Antibacterial surfaces wouldn’t need to be cleaned regularly with stro ng che m icals . It wo u ld be wonderful if hospital beds, railings, door knobs, and other surfaces couldn’t gather populations of harmful germs . Engineers could also build these surfaces into medical implants, such as artificial hips or knees or pacemakers for the heart. Medical implants with antibacterial surfaces would be much safer to use . “The end goal is a prosthesis that I can implant with clinical evidence that it kills bacteria and reduces the infection rate,” said Oliver Pearce, a surgeon at Milton Keynes University Hospital in the UK.

Beetles’ Backs

Another insect, the Namib Desert beetle, also has an intriguing body surface that engineers are trying to recreate. This beetle lives in the Namib Desert in southwestern Africa . Rain rarely falls here. But the air regularly gets windy and foggy. When it does, the beetle simply raises its rear end into foggy wind. Water carried in the air hits the beetle’s back, condenses into droplets, and then rolls down its back and into its mouth.

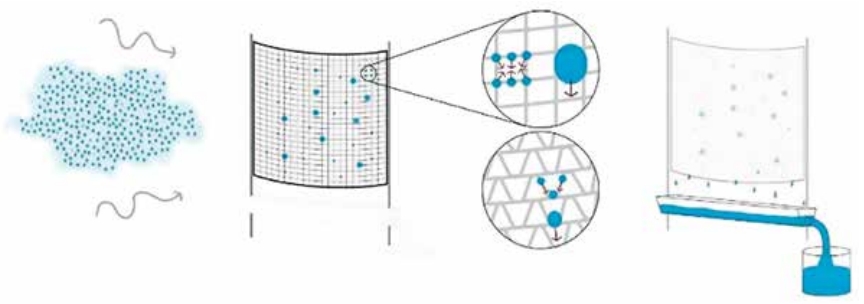

If people could easily gather water from fog, they could use that water for drinking or farming in parts of the world where clean water is scarce . People already use nets and meshes to collect water from fog. These materials work, but don’t collect very much water. If the holes in a net are too big, the water droplets fall out. If the holes are too small, they get clogged and the water won’t flow into the collection container.

The beetle’s back isn’t at all like a net. Instead, it’s studded with bumps. Water easily sticks to the bumps . In between the bumps, though, the beetle’s smooth back repels water. So molecules of water roll off the smooth parts and stick onto the bumps. This forces the water in the fog to collect together into liquid droplets that are large enough to roll down the insect’s back.

Engineers have been trying to recreate this sort of surface. The trouble is that they have to make the bumps out of a material that water easily sticks to, but they have to make the main surface out of one that water won’t stick to. “Such a surface is very difficult to make,” Peng Wang of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia told Chemistry World. His team managed to make such a surface in 2014 using an inkjet printer.

In 2019, another team of scientists improved on this idea. They noticed that everyone trying to imitate the beetle’s back was making flat surfaces studded with bumps. But the beetle has a curved shell. Perhaps a curved surface would work better. They found that a curved surface covered with water-attracting bumps collected sixteen times more water than a flat one with the same kinds of bumps.

Have you noticed anything fascinating about the animals that live around you? Or have you seen an animal at a zoo or farm doing something humans can’t do? How could you engineer something that gives humans the same ability? Take some notes, make some sketches or models, and do some research. If you have access to the right materials and adults who can help, build a prototype. But remember that you’ll likely have to go back to the drawing board many times before your invention works as you planned. If you persevere, you could be the next person to change the world with biomimicry.