制)

The human body works like a machine. Over time, its parts wear out or get damaged. For example, disease may weaken the heart or a bone may break. When the body cannot heal itself, a doctor may repair or replace diseased or broken parts to keep the body running smoothly. Sometimes, a living or dead human donor provides a part. Donations of hearts, lungs, kidneys, bone marrow, blood, and other tissues regularly save lives. But getting new parts from other human beings isn’t the only way to accomplish this.

Tissue engineers also make new parts that work inside the human body. Lots of people walk around every day using hip or knee joints made of metal. People with heart disease may get metal heart valves or metal pieces called stents that keep arteries open. Some people receive total artificial hearts made of metal and plastic. These machines take the place of recipients’ hearts.

Metal and plastic parts work for some purposes. But tissue engineers have grander visions. They are working to create living body parts that contain human cells. They have made artificial skin, bone, cartilage, arteries, and even pieces of organs.

Regenerative Medicine

人造细胞基质材料,将人类干细胞在人工

环境中培养,然后再植入人体

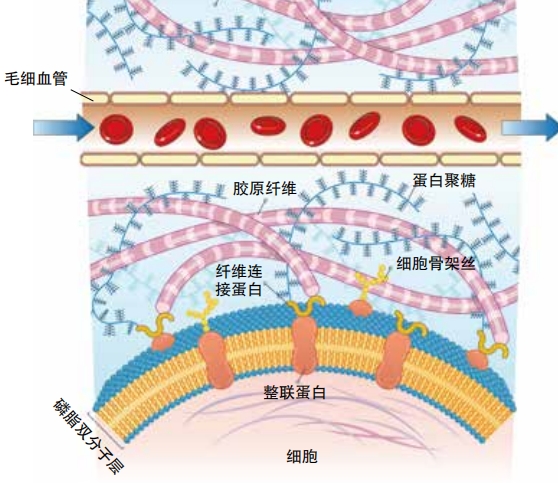

A living body part is not one material, like plastic or metal. It contains many different materials, all working together. A lung, for example, contains billions of cells of forty different types. Many of those form the six hundred million tiny air sacs that allow you to breathe. Others form a complex network of blood vessels. These channels feed all the cells in the lung and carry away their waste. The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a non-living material that acts like the scaffold on a building under construction. It holds all the cells and air sacs and vessels, giving the lung its shape and structure. All living tissues in the body contain some combination of cells, vessels, and an ECM that holds everything together.

No one has yet managed to recreate an entire lung, heart, kidney, or any complex organ. Most experts predict that it will take ten to twenty years before doctors rely on engineered organs instead of ones donated from other humans. But tissue engineering is already changing medicine.

One important thing to understand is that doctors don’t necessarily have to rebuild an entire organ or tissue from scratch. The field of regenerative medicine takes advantage of the body’s ability to heal itself. When you get a paper cut, for example, your finger doesn’t stay sliced open forever. Within a few days, new skin grows to fix the injury. When you break a bone, the bone eventually regrows to fix the break. The liver can also regrow entire sections of itself. But cartilage (the material that forms joints between bones) doesn’t regrow in adults. And most areas of injury or disease can’t heal on their own.

This is where biomaterials can help. For example, if a section of someone’s skin, muscle, cartilage, or bone has to be replaced or rebuilt, a doctor may be able to implant a temporary ECM. This acts as a scaffold for the body to use to regrow the damaged part. This scaffold doesn’t have to contain any cells or blood vessels. The body will regrow its own cells and blood vessels onto the structure. Over time, the temporary scaffold should degrade or dissolve as the new cells form their own ECM around themselves. “If we can implant the scaffold, it can serve as a bridge to help the body do regeneration,” explains Adam Feinberg, a biomedical engineer at Carnegie Mellon University.

Building a Scaffold

How do tissue engineers build that scaffold? They have experimented with a wide range of biomaterials. Some come from natural sources and others are synthetic. The scaffold material must meet certain requirements. First of all, it must be non-toxic and safe to use in the body. The body must not reject the material or attack it. Second, the material should degrade over time as the body rebuilds its own ECM. Third, the material must be strong. It must not break, tear, or deform while being manufactured or transferred into the patient. Yet the material must also match the properties of the tissue it is meant to replace. Most human tissues are soft and contain lots of tiny, interconnected spaces inside their structure. These spaces allow blood vessels and other channels through. Finally, a factory must be capable of making lots of the scaffold material. If researchers can only make a scaffold one at a time in a laboratory, the technology will never reach patients who need it.

Tissue engineers don’t have to create a new material to use as an ECM. They can take tissues from deceased people or animals, wash away all the cells, and reuse the empty ECM as a scaffold for new cells to grow onto. This is called tissue decellularization and recellularization. Some researchers have even experimented with decellularizing spinach leaves and other plant tissues to use as scaffolds for human cells.

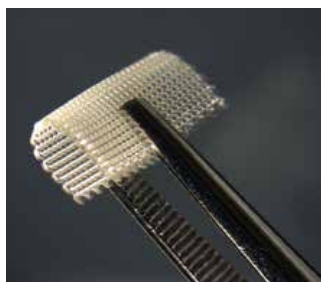

An empty ECM (from a person, animal, or plant) contains the necessary tiny holes and channels for growing cells to fill. But engineers can’t control this structure. And scaling up production of decellularized tissue is not easy to do. So engineers are also working on ways to 3D print or manufacture scaffolds for human tissues.

Some o f these scaffolds are made in the form of a sponge or foam, a squishy material full of tiny holes. Others are hydrogels, or networks of polymers that tend to absorb water easily. These are very similar in structure to the natural ECM. Still more scaffolds are formed from tiny threads called nanofibers, or from teeny tiny balls of material called microspheres.

Natural Materials

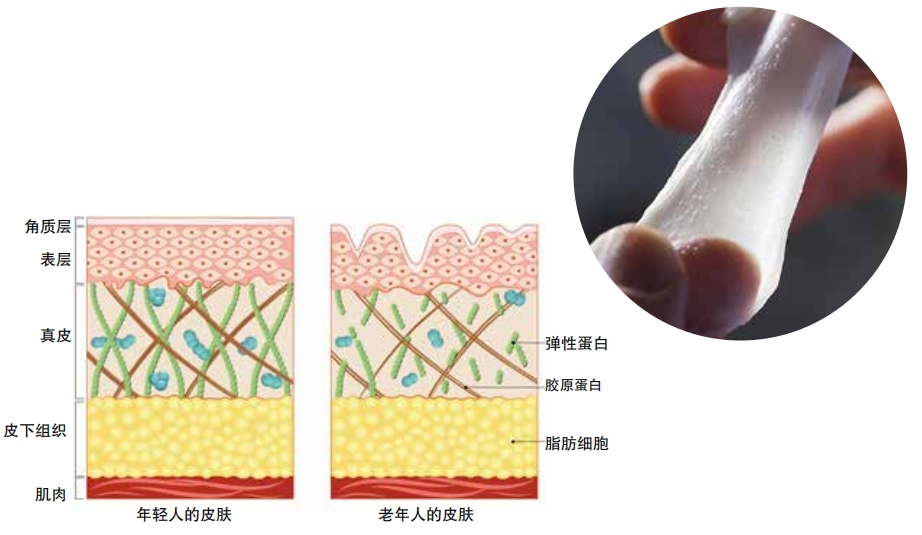

The material for these scaffolds comes from a range of sources. The main ingredient of the body’s natural ECM is collagen. It’s a protein made of very strong but flexible strands of molecules. Collagen is what makes skin strong and stretchy. (As collagen molecules break down in elderly people, their skin gets wrinkled and saggy). Since collagen is already a natural part of the ECM, it’s an obvious choice for engineering scaffold.

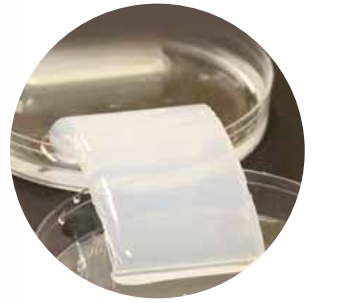

Collagen can be extracted from dead animals o r human remains and then purified for use in tissue engineering. In 1976, biongineer Ioannis Yannas of MIT and Dr. John F. Burke of Harvard Medical School combined cow collagen with shark cartilage to make one of the first artificial skin scaffolds. The material they developed, called Integra Dermal Regeneration Template (Integra DRT for short), is still used today to mend sections of human skin lost to burns or other injury or disease. However, collagen taken from cows isn’t safe for all patients. Some people have an allergic reaction to it. So researchers have found ways to grow human collagen in plants and bacteria.

Other natural materials can mimic the ECM and act as a scaffold to support cell growth. Sodium alginate is a powdery substance extracted from brown seaweed. Food manufacturers put it into pudding, jam, tomato juice, and other canned products to thicken them and help keep them from separating. Tissue engineers have used a gel form of sodium alginate to create scaffolds to use for skin growth. They’ve also investigated using this material as a scaffold for regrowing cartilage in the joints.

Chitosan is another promising biomaterial. It comes from chitin, a natural substance found in sea animal’s shells as well as in some types of mushrooms. Researchers have found that it works well when used as a scaffold for wound healing. Spider silk has also shown promise as a scaffold material.

Natural scaffold materials tend to be safe for use in the body and degrade well over time, but they also tend not to hold up well during manufacturing and implantation. And their structure is often inconsistent or unpredictable.

Synthetic Materials

Synthetic scaffold materials may not be porous or soft enough, and it is more difficult to make them safe for use in the body. But on the positive side, they can be made to be very strong and durable. Also, their structure can be carefully controlled and it’s usually much easier to produce them in bulk. Most synthetic scaffolds are made of polymers, or long chains of repeated molecules. (Plastics are also made of polymers.) PLA, PGA, PLGA, and PCL are all popular choices for synthetic scaffolds that work well with 3D bioprinting equipment.

In 2017, a group of researchers used a 3D bioprinter and the polymer PCL to form a section of a trachea, the tube that brings air to an animal’s lungs. They successfully implanted the material into rabbits, replacing a segment of each rabbit’s trachea. The procedure went well. Eventually, a material like this could help children whose throats do not form correctly or get damaged.

PuraMatrix is another example of a synthetic scaffold product. MIT researcher Shuguang Zhang began working on the biomaterial in the early 1990s after an accidental discovery. He’d left cells in the lab overnight in the same dish as some peptides (a building block of proteins). He’d expected the cells to die. But to his surprise, the cells grew. “That aroused my curiosity, so I chased it,” he told MIT news. “Curiosity is so important to scientific discovery.” After a decade of effort, his team developed a hydrogel that contains those peptides. When exposed to salt, the peptides form themselves into a strong scaffold. The material is nontoxic and safe to use in the body. It could be used to help the body regenerate cartilage, bone, skin, or heart muscle.

When it comes to replacing or regrowing bone or teeth, the ceramic material hydroxyapatite has shown a lot of promise. This material is found naturally in human bones but can also be produced synthetically. Like most ceramics, it is hard but easily broken. So tissue engineers have figured out how to mix the material with a polymer such as PCL to make it stretchier. The result is a biomaterial that is friendly to the body and can be 3D printed in any shape. This means doctors could form it into the shape of a missing section of bone, then the body could use that scaffold to grow new bone cells. Right now, surgeons who need to rebuild a bone often move material from other parts of a person’s body or use metal implants. A mixture o f hydroxyapatite and PCL could mean faster, less painful procedures and an easier recovery for patients.

Another type of ceramic material, bioactive glass, will bond to bone. The product 45S5 Bioglass was originally developed to treat bone defects and injuries that wouldn’t heal on their own. But now researchers have learned that the material can also help blood vessels grow into a soft tissue scaffold. Combining bioactive glass with soft scaffold materials, such as chitosan, could make scaffolds that are easier for the body to use.

Growing:Brand New Bladders and More

Most procedures today that use biomaterials to replace sections of skin or other human tissue implant only a scaffold. The body’s natural healing processes do the rest of the work. But many doctors and researchers are working on ways to combine a scaffold with living cells in the lab, with the goal of growing complete tissues or even organs for implantation.

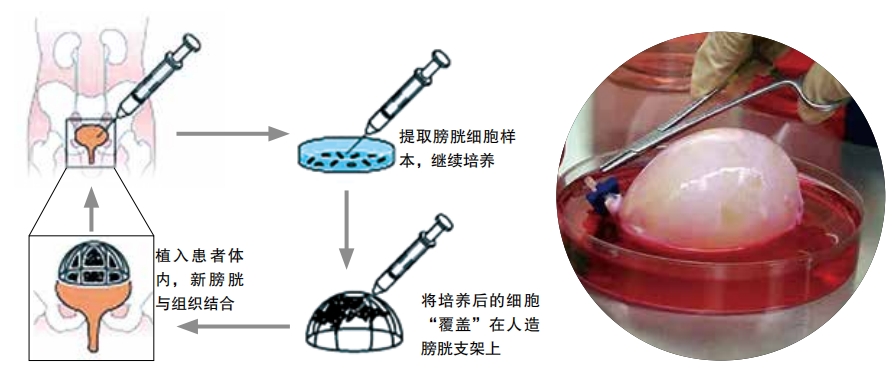

The easiest human tissues to grow in a lab are flat or tubular, like skin, blood vessels, or the urethra (the tube that carries urine). It’s also possible to grow hollow structures such as the trachea or bladder. Anthony Atala, a surgeon at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, has already successfully grown and implanted engineered bladders into patients.

The first engineered bladder transplants took place in 2006. Atala’s team first took a postage-stampsized sample of bladder cells from each patient. In the lab, they formed a bladder shape from a combination of a synthetic polymer and collagen. Then they covered the shape with cells from the patient’s sample. They kept the cells alive in a vat of nutrients until it was time to implant the new bladder into a patient. Luke Massella received one of those bladders when he was ten years old. He needed it because he had been born with the condition spina bifida, which had made his bladder stop working properly. Seventeen years later, his new bladder was still working. He was able to lead a more normal life thanks to the surgery.

Researchers can keep flat or hollow structures alive in a lab because the living cells are spread out in a thin layer on the surface. All of the cells can reach the nutrients in a vat. A thick piece of tissue or a dense organ, like a lung or kidney, requires a network of blood vessels. Tissue engineers call this network vasculature. Without vasculature, the cells in the middle of the tissue won’t get oxygen or nutrients and will die. Building vasculature into engineered tissue is an unsolved challenge. NASA is offering a $500,000 prize to the first team to keep the cells inside a onecentimeter thick piece of engineered tissue alive for thirty days .

Researchers can keep flat or hollow structures alive in a lab because the living cells are spread out in a thin layer on the surface. All of the cells can reach the nutrients in a vat. A thick piece of tissue or a dense organ, like a lung or kidney, requires a network of blood vessels. Tissue engineers call this network vasculature. Without vasculature, the cells in the middle of the tissue won’t get oxygen or nutrients and will die. Building vasculature into engineered tissue is an unsolved challenge. NASA is offering a $500,000 prize to the first team to keep the cells inside a onecentimeter thick piece of engineered tissue alive for thirty days .

Once tissue engineers solve the vasculature problem, they should be able to start designing larger pieces of tissue and eventually entire organs. Around twenty patients on organ transplant lists in the United States die each day while waiting for a heart or lung or other organ that never comes. Atala hopes that his work will lead to a future in which no one will have to wait “for someone to die so they can live .” Hopefully, tissue engineers and doctors will find the materials and manufacturing methods they need to repair or replace any damaged part of the human body. In the future, people may lead much longer, healthier lives thanks to biomaterials.