King Tutankhamun only ruled ancient Egypt for a few short years before dying as a teenager. His mummy was discovered in a tomb filled with gold and jewels. But what killed him? He had been sickly throughout his whole life and had a broken leg when he died. But scientists found traces of a terrible disease that likely ended his life. That disease is called malaria.

Malaria typically feels like a terrible flu. Victims may have a high fever, chills, joint pain, a headache, diarrhea, vomiting, a cough, a racing heart, or rapid breathing. Sometimes these symptoms come and go as periodic attacks. A severe or untreated malaria infection can lead to kidney failure, seizures, coma, and death.

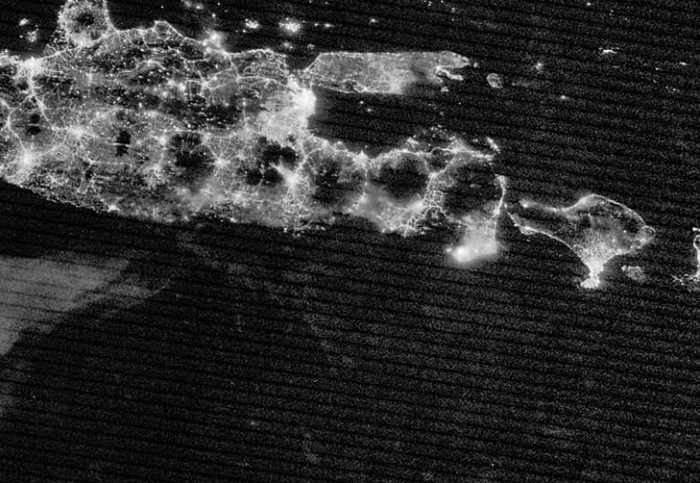

In 2022, malaria sickened about 249 million people around the world and killed 608,000. Sadly, infants, children under 5 years, pregnant women are at higher risk of severe infection. In some countries, malaria is the leading cause of death and disease. Thanks to prevention and control efforts, malaria is no longer common in the United States, Europe, or China. But cases do still occur occasionally in these regions. And as the climate warms, many experts predict that the threat of malaria will rise worldwide.

A Long History

Many ancient texts, including ones from Egypt, India, China, and Greece, mention diseases that were likely malaria. One ancient text from India calls it the “king of diseases.” Some historians think a malaria epidemic during the first century AD contributed to the fall of Rome.

European settlers and their slaves carried malaria to the United States, where it killed many Native Americans, sickened several presidents, and downed many soldiers of the Civil War. The Centers for Disease Control in the United States was originally founded to control malaria.

The name malaria comes from the Italian phrase mal aria, or “bad air.” Ancient Romans thought the bad air in swamps caused the disease. They were wrong about bad air but right that swamps play a role. Swamps are where mosquitoes go to breed, and mosquitoes spread malaria. But it’s not the mosquito itself that makes a person sick.

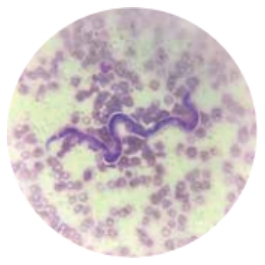

A malaria-carrying mosquito is what epidemiologists call a vector. This is a living thing that carries or transfers a disease. When a mosquito bites a person with malaria, a tiny single-celled parasites enter the mosquito, and then the infected mosquito will spread the parasites to the other people it bites. It’s the parasites that wreaks havoc on the body.

A malaria-carrying mosquito is what epidemiologists call a vector. This is a living thing that carries or transfers a disease. When a mosquito bites a person with malaria, a tiny single-celled parasites enter the mosquito, and then the infected mosquito will spread the parasites to the other people it bites. It’s the parasites that wreaks havoc on the body.

Since mosquitoes transmit malaria, the disease spreads most easily in places with lots of these biting insects. Malaria will not spread at very high altitudes, during very cold winters, in most deserts, or in areas that have managed to control their mosquito populations. In warm, wet, tropical areas near the equator, mosquitoes are active all year long. In these areas, malaria is much more likely to occur and spread.

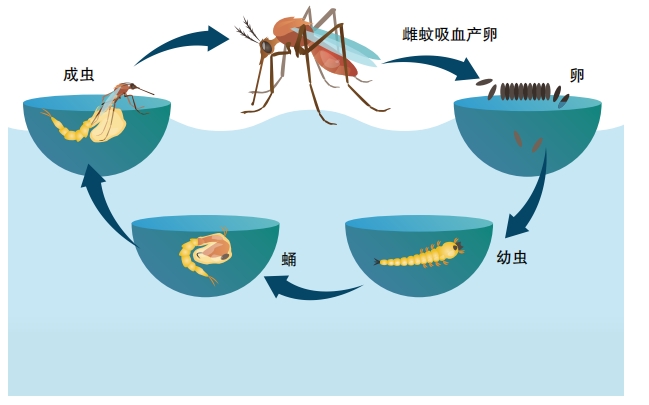

Life Cycle of a Killer

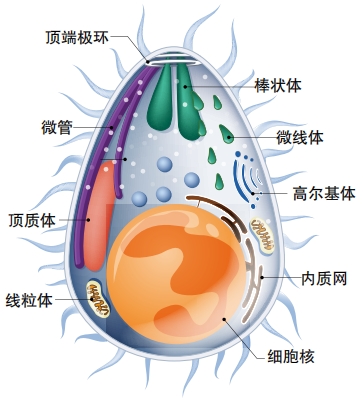

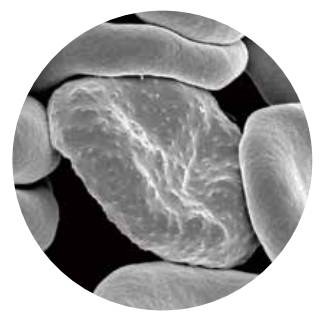

The parasites that cause malaria are one-celled creatures called protozoa that belong to the genus plasmodium. Five different species can cause malaria, but two of them are the most dangerous, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax.

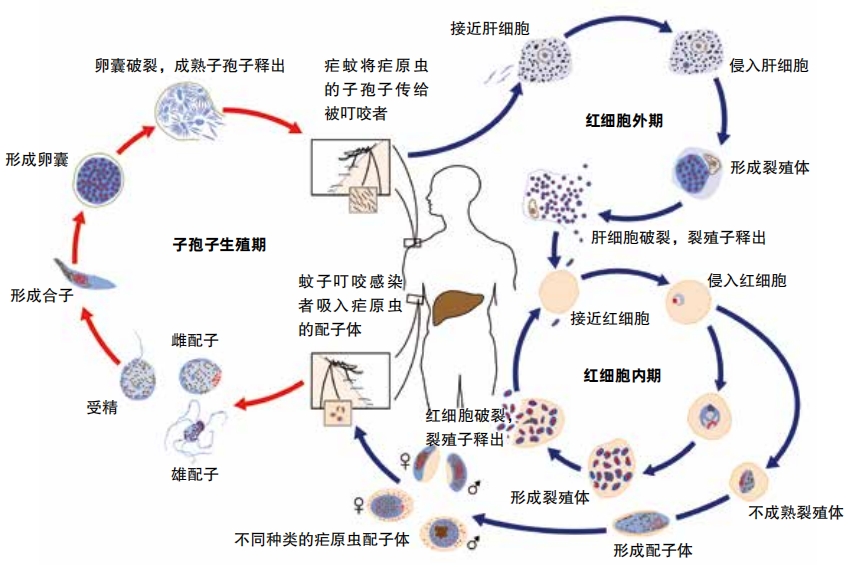

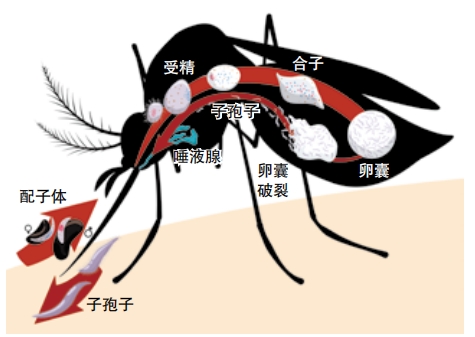

This one-celled creatures develop into sporozoites in mosquitoes. When an infected mosquito bites a human body, sporozoites into the person’s bloodstream and end up in the liver.

In the liver, the baby parasites reach their next stage of life. They begin to divide and reproduce until they mature into forms known as schizonts. Each schizont multiplies into thousands of daughter cells called merozoites, which can cause liver cell rupture and enter the bloodstream. Then they live inside red blood cells. They divide and multiply until the red blood cells burst. This is when a person feels symptoms of disease.

Some of the blood-cell invading merozoites keep multiplying asexually. But others mature to become males or females. These are called gametocytes. When a mosquito bites this person and drinks his blood, it ends up eating gametocytes too.

Inside the mosquito, gametocytes fertilize each other and form an oocyst in the mosquito’s gut. When the oocyst bursts, sporozoites emerge and travel to the mosquito’s saliva, ready to infect whomever the mosquito bites next.

Mosquitoes, unfortunately for us, do not get sick during this process. If mosquitoes did get sick and die of malaria, they wouldn’t be so good at spreading the disease!

Drug Discoveries

The first cure for malaria came from a natural source: the cinchona tree, native to South America. Its bark contains a chemical compound called quinine that kills plasmodium parasites or prevents them from growing. It also treats some other kinds of fevers. The Quechua, Cañari and Chimú indigenous peoples knew about this medicinal tree bark long before European colonizers arrived. In 1630 in Peru, local people taught a community of Spanish Jesuits how to use cinchona bark to cure fevers.

Soon, the bark of the cinchona was in high demand. By the 1850s, Britain was planting cinchona, which had been nicknamed the “fever tree” on plantations in India. The British used it to help treat malaria outbreaks in their colonies. About a century later. chemists managed to make artificial quinine in a lab.

Along the way, chemists discovered molecules very similar to quinine that had similar effects. German scientists created chloroquine in 1934. At first, they thought it was too toxic to be used as a medicine. But later research showed this to be a mistake, and after World War II, it became a very important anti-malaria drug.

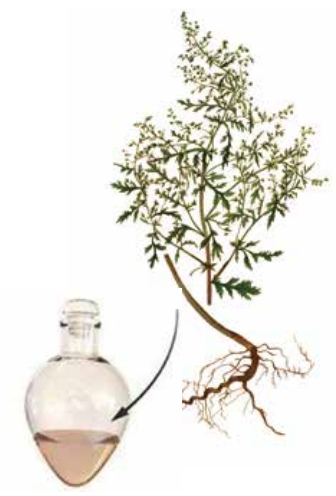

In China in the 1970s, medical researcher Tu Youyou studied traditional herbal medicines looking for malaria remedies. She found a substance called artemisinin in a plant called Artemisia annua. Artemisinin kills or harms plasmodium parasites and can cure malaria. Youyou earned the 2015 Nobel Prize in Medicine for her discovery.

These drugs have all saved numerous lives. Yet, over time, parasites develop resistance so some experts fear the protozoa will survive malaria treatment. “The parasite is so plastic, so malleable … If you let up pressure, it will evolve, it will change, it will come back,” Chris Plowe, a malaria expert at the University of Maryland, told NPR. When that happens, the usual drugs won’t work. Diana Menya told Duke Global Health Institute that she worries that “we’re going to run out of drugs for malaria.” Menya is an epidemiologist at Moi University School of Public Health in Kenya.

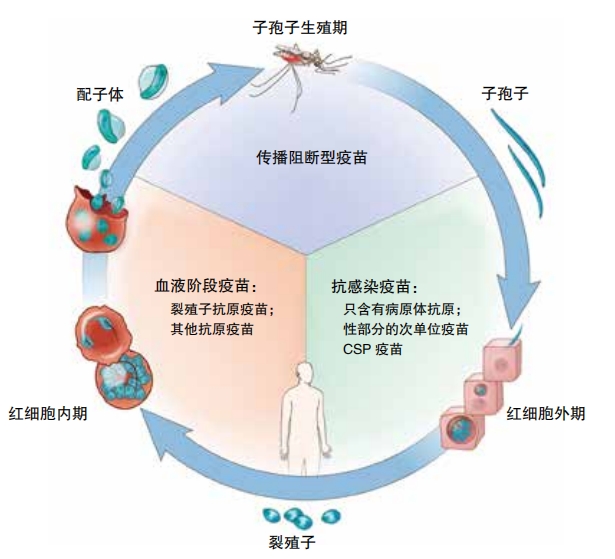

What if there were a way to protect people from malaria before they get sick? Since the 1960s, researchers have been working to develop malaria vaccines. Vaccines work by preparing the body’s immune system to battle a threat. However, parasites have very complex life cycles. They evolved to evade the human immune system’s attacks. For example, P. vivax can leave dormant cells behind in the liver. These may survive even if all the P. vivax circulating in the blood gets wiped out.

With some illnesses, if you catch it once, you become immune in the future. Malaria doesn’t work that way. People can catch it again and again. Their body may do a better job resisting new infections, but they aren’t immune against malaria.

A New Hope

Developing vaccines for malaria and other parasitic diseases proved to be an incredibly difficult challenge, but hard-working researchers have risen to meet the challenge. In 2021, the world’s first malaria vaccine, RTS,S/AS01 (also known as Mosquirix), was approved for use, and in October 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) approved a second vaccine, R21/Matrix-M.

Malaria vaccines block one or more parts of the plasmodium parasite’s life cycle. RTS,S/AS01 and R21/Matrix-M are both pre- erythrocytic vaccines. It means that these vaccines fight malaria before it enters the blood. Both vaccines go after sporozoites, those baby parasites that set up camp in the liver. They teach the immune system to attack sporozoites as they try to reach the liver and also purge them from infected liver cells.

The R21/Matrix-M vaccine targets a protein on the surface of the sporozoite called the circumsporozoite protein (CSP). When the R21 component of the vaccine, which includes a part of the CSP, is introduced into the body, it prompts the immune system to recognize and mount a defense against this protein. If the vaccinated individual is later exposed to the malaria parasite, their immune system is primed to identify and attack it based on the recognition of the CSP

Malaria vaccination pilot programs in Kenya, Ghana, and Malawi showed that children who received a vaccine were 13 percent less likely to die–not just of malaria, but of any cause. That’s likely because malaria often worsens other medical problems or puts a child at higher risk of catching some other disease that could be deadly. So protecting against malaria also protects kids from deadly combinations of malaria with other illnesses.

Rebecca Adhiambo Kwanya of Kisumu, Kenya got her youngest child, eighteen-month-old Bradley, vaccinated during the pilot program . “My elder one was not vaccinated and he was sick on and off,” she said. “But the smaller one, he got the vaccine and he was not even sick.” In January 2024, Cameroon began the world’s first mass malaria vaccination program for children.

Mosquito Hacking

Remember that a malaria infection begins with a bite from an infected mosquito. Over the years, many malaria prevention efforts have focused on these insects. Stop the mosquito bites, and you can stop malaria. Simple measures like sleeping with nets over beds or draining standing water where mosquitoes like to breed can help fight the disease. So can spraying insecticides that kill mosquitoes.

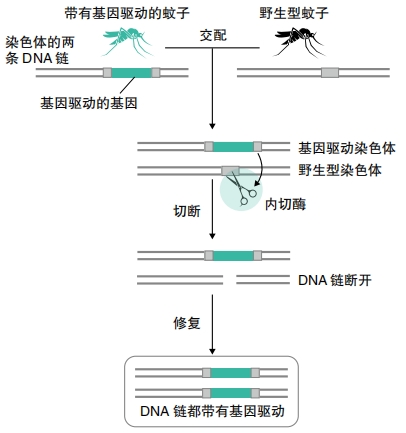

But mosquitoes are hardy insects that easily bounce back from people’s attacks. “To try to get rid of them, I don’t think it’s possible,” Anthony James told NPR. He’s a biologist and geneticist at the University of California, Irvine. His team is one of several working on genetically engineering mosquitoes to help prevent the spread of malaria.

Normally, mosquito immune systems don’t try to kill the plasmodium parasite since it doesn’t harm the bug. So James’s team took genes that fight off the parasite from mice and gave them to mosquitoes. This worked to reduce the number of parasites that survived inside treated mosquitoes, they reported.

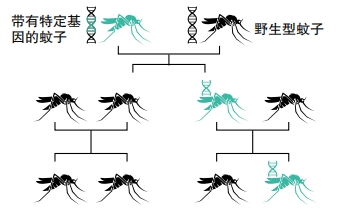

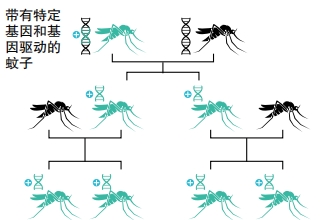

Other researchers are working on more extreme approaches. For example, one genetic modification kills all female mosquitoes. Another makes it impossible for females to bite or lay eggs. When these engineered mosquitoes mate with wild ones, they spread the modification through a process called a “gene drive.” Normally, traits have a fifty-fifty chance of getting passed on. But using a gene drive ensures that a gene gets transferred to all offspring. This could potentially wipe out an entire mosquito population. “This technology has the potential to be the safe, controllable and scalable solution the world urgently needs to eliminate malaria once and for all,” said Omar Akbari. He’s a biologist at the University of California San Diego.

However, other experts worry about the unknown side effects that gene drives might have on biodiversity. Taking out mosquitoes would impact the creatures that feed on them, which could have a negative impact on the environment. “This is a technology where we don’t know where it’s going to end. We need to stop this right where it is.” Nnimmo Bassey told NPR. He is director of the Health of Mother Earth Foundation in Nigeria.

The scientists who are studying gene drives for mosquito control are aware of these issues. They are testing the environmental impact of the technology. They hope that someday, their work will save lives. “The known harm of malaria so outweighs the combined harms of everything that has been postulated could go wrong ecologically.” Kevin Esvelt told NPR. He’s an evolutionary engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The world has come a very long way since malaria took the life of a young Egyptian king. We are fighting back against this deadly disease with medicines, vaccines, and mosquito-control efforts. But the battle is far from over.

Neglected Tropical Parasitic Diseases

Malaria is the deadliest parasitic disease in the world, but it’s not the only one . The World Health Organization tracks a group of twenty neglected tropical diseases . These diseases are most common in hot , humid parts of the world where fresh water and clean sanitation aren’t easily available. Four of the most common ones are caused by parasites and don’t typically lead to death . “Even though these aren’t killing people, these are causing a huge amount of suffering,” says Dr. Peter Hotez . He’s a pediatric medical scientist at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston .

Dr. Hot ez is the one who popularized the concept of neglected tropical diseases . He says that they “trap populations in poverty. ” That happens when they stunt children’s development and prevent adults from working. In his opinion, developing vaccines for these types of diseases is an important part of the fight against poverty.

Here are the most common four :

·Lymphatic filariasis (also called elephantiasis)

A parasitic roundworm causes this disease that may lead to painfully swollen, enlarged, and disfigured body parts .

·Onchocerciasis (river blindness)

Blackfly bites transmit the parasitic worms that cause this condition when they migrate to the eyes where they can cause blindness.

·Schistosomiasis (snail fever)

The parasitic flatworm that causes this disease lives in snails for part of its life . In water, the eggs hatch and release immature schistosome larvae . The larvae swim and enter a snail . After the larvae develop , they are released from the snail into the water and penetrate the skin of people who enter the water. It may cause a rash, fever, cough, and achi ness. Untreated cases may lead to liver and bladder problems.

·Soil-transmitted helminthiases (intestinal worms)

Varieties of parasitic worms, including roundworm, hookworm, and whipworm may infect people who live in areas with poor sanitation. In the short-term, these worms may cause intestinal pain and diarrhea . But the long-term effects are far worse . “These worms basically rob kids of their full potential in terms of intellectual and physical development,” says Dr. Peter Hotez .