You wake up and open your eyes, your head is pounding. Maybe a little breakfast will help. You try a few bites of an egg on toast, but your head hurts too much to eat. Maybe you’re getting sick? With a groan, you walk to the medicine cabinet. You find a bottle of Tylenol. (The technical name of this medicine is acetaminophen). You pop a pill in your mouth, take a gulp of water and swallow. Then you lie down and wait. As the medicine starts to work, your headache will go away.

What goes on in your body after you take medicine? Let’s find out. Along the way, you’ll learn the secrets of pharmacology, which is the study of drugs.

Pills, Syrups, Ointments, Syringes, and More

Drugs need to get into the body to work. Swallowing a pill is easy and convenient. That’s why so many drugs come in pill form. However, there are many other ways to take medicine. Tylenol for young children comes as a syrup because it is easier to swallow than a pill.

Some medicines aren’t meant to be swallowed. Instead, the patient holds a pill either against a cheek, under the tongue, or on top of the tongue until it dissolves. Or the patient sprays some medicine into the nose. Because of the abundance of capillaries and thin mucous membranes in the mouth and nose, That medicine can then enter the blood without having to go through the stomach first.

You apply some medicines directly to a certain part of the body. These medicines go straight to work on that body part. For example, skin ointments help repair or protect problems on the skin, like rashes or burns. Some eye medicines come as a liquid that you drop into the eye. People with asthma use inhalers to breathe in their medicine from the mouth into the respiratory tract.

Other medicines come in a suppository. This type of medicine gets inserted into the rectum, urethra, or vagina. Suppositories often treat diseases in these areas, and also melts inside the body and is absorbed directly into the bloodstream, so it is tends to work quickly.

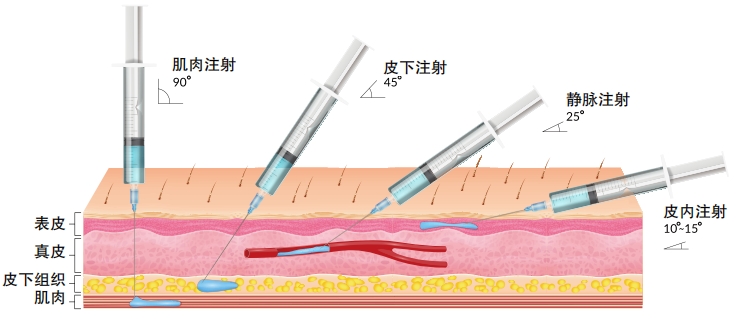

One very direct way to get medicine inside the body is to inject it in with a needle. An injection into the tissue between the skin and muscle is called a subcutaneous, it works more slowly. People with diabetes must inject the hormone insulin this way. An injection into muscle is called an intramuscular injection, which works faster. A woman who has trouble getting pregnant may need hormones to help boost her reproductive system and trigger ovulation. She will often need subcutaneous or intramuscular injections.

An injection into the vein and directly into the bloodstream is called an intravenous injection, or IV. In an emergency or during surgery, doctors usually set up an IV, which can quickly and easily give a patient fluids or medicines.

Into the Bloodstream

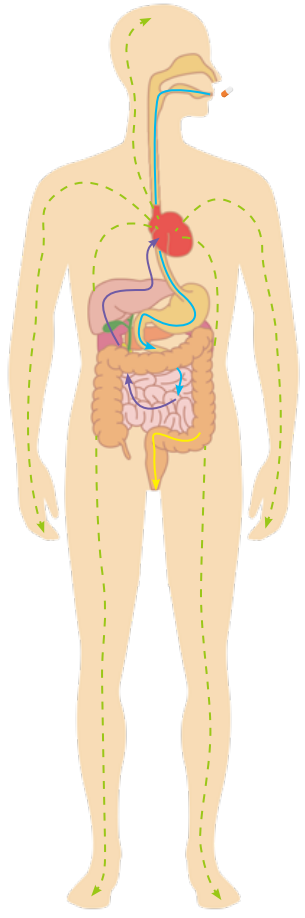

Most medicines must get into the body’s bloodstream in order to do their job. Pharmacologists call this process absorption. Blood vessels are like the roads of the body. The roads carry blood cells and blood plasma. Plasma is a light, yellowish liquid that holds all blood cells and makes up a little more than half the volume of all the body’s blood. Blood cells mainly include red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets. Like a fleet of delivery trucks, the blood cells and the plasma transport oxygen and nutrients throughout the body and cart away waste products produced by the cells. When medicine gets into the blood, it ends up on these delivery trucks too. An IV medicine entering directly into blood, it will start working almost immediately. Inhaled medicines and ones sprayed in the nose, or dissolved on the cheeks or tongue absorb directly into the blood and start working extremely quickly.

Other medicines need to go on a longer journey to get to the bloodstream. That’s why you usually don’t feel the effects of a swallowed pill for at least half an hour.

Those Tylenol pills you swallowed journey down your throat and into your stomach. They join the bites of toast and egg you ate for breakfast. The pills (and the food) won’t always stay in the stomach. The stomach’s job is to break down everything that passes through. Strong acids and chemicals called enzymes break food into smaller pieces. Most pills get broken down in the stomach as well. Some pills have several layers of special coatings. The coatings are meant to breakdown slowly so that the pill can keep supplying the body with medicine for a long time.

Some drugs can’t survive a trip through the stomach. The acids and enzymes in the stomach will destroy them before they ever get to the bloodstream. So doctors must use other forms, such as injections or pills that dissolve under the tongue, to give these drugs.

The stomach turns the Tylenol pills into Tylenol mush. This mush mixes with everything else in the stomach. It gets pushed into the small intestine. This organ is a long, hollow tube. Its walls act a bit like sponges that soak up very tiny bits of food, water, and anything else in the small intestine—including medicine. These bits pass through the wall and into the bloodstream.

Sometimes, a pharmacist will suggest that you take a pill with food or just after eating. That makes sure that the stomach is filled with food and digestive juices as well as the medicine. Everything gets absorbed all together.

However, all medicines work differently. Some must be taken on an empty stomach. That’s because food can affect the absorption of these drugs. Some antibiotics won’t work well if you’ve had milk, yogurt, or cheese. That’s because the medicine will bind to the calcium in dairy foods and doesn’t get absorbed correctly. It’s always important to follow instructions when taking medicine.

Zooming Around the Body

The blood leaving the small intestine pass through the liver. That’s the next stop for the tiny bits of Tylenol. The liver is like a checkpoint at a country’s border. One of its jobs is to stop harmful substances from getting into the body further. The liver will often toss out some bits of medicine because it doesn’t recognize the stuff. (We’ll talk more about this in the next section). Usually, most of the molecules of active medicine make it on to the heart. From there, they go on a road trip around the body.

This is no lazy road trip. Imagine the medicine traveling in a race car! On average, it takes just one minute for a blood cell to leave the heart, travel around the body, and then return to the heart. There, the blood cell refuels with oxygen from the lungs and then zooms off on another trip. Anything else traveling in the blood moves at the same rapid speed. As blood circulates, the medicine spreads throughout the body. Pharmacologists call this distribution.

The Tylenol you took travels in your blood plasma. It’s traveling companions are nutrients, hormones, proteins, and more. During distribution, a medicine reaches many parts of the body. You took Tylenol for a headache. But while the medicine is travels in your blood, it will reach body parts and systems that aren’t in pain and don’t need any medicine. It may even end up in your hair!

The fact that medicines spread everywhere is one reason for side effects. While the drug may have a positive effect on one part of your body, it may have a negative effect somewhere else. Also, most drugs spread unevenly through the body. The organs with the most blood vessels and highest volume of blood flow, including the heart, liver, and kidneys, typically receive the most medicine. Taking too much medicine or abusing drugs may damage these and other organs.

Different types of drugs also spread out differently. If a drug dissolves in water, it may stay in the blood or the spaces between body cells. If it dissolves in fat, it will end up in fatty tissues. Some tissues absorb certain types of molecules more easily than other tissues. For example, the thyroid, a gland in your neck, produces hormones that help control many body processes. The thyroid is the only part of the body that can absorb iodine. Pharmacologist have used this fact to design iodine- based medicines for thyroid cancer. The medicines end up in the thyroid but almost nowhere else in the body.

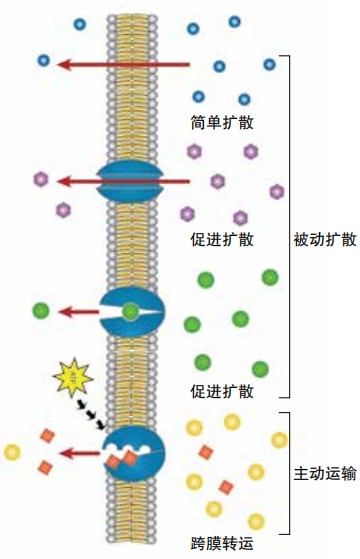

Most medicines get into body cells thanks to passive diffusion. This is a process similar to a sponge soaking up water. As long as the sponge is dry, water seeps into it. For many medicines, as long as a cell doesn’t contain too much of that medicine, it will seep in. Other medicines get through cell walls and membranes thanks to active transport. That means the cell either opens up a door for the medicine to enter or sends out proteins to bring the medicine in, like a person receiving a delivery.

A special membrane called the blood-brain barrier acts like a wall to protect our brain. It prevents many medicines from reaching the brain. The first antibiotics, penicillin, does not easily pass through this wall. So it doesn’t usually reach the brain. Tylenol, however, can pass into the brain. That’s most likely where it does its job of blocking the pain of your headache. Current research suggests that, Tylenol most likely blocks an enzyme that the brain uses to respond to pain. So while Tylenol is doing its job, the brain can’t respond to any type of pain as strongly as it normally would.

Stopped at the Checkpoint

As blood travels around the body, it regularly passes through the liver. As mentioned before, the liver is like a checkpoint at a country’s border. Blood passing through gets checked to make sure the stuff it carries belongs inside the body. Anything that came from outside of the body—including food and medicine—gets transformed so that the body can either use it or get rid of it. This transformation is called metabolism.

Metabolism is how the body turns food into energy. The liver also metabolizes toxins to turn them into less dangerous substances. You may know that drinking too much alcohol damages the liver. That’s because the liver has to work hard to detoxify alcohol. If a person drinks more than the liver can handle, it will be damaged. An overdose of Tylenol will also cause liver damage.

When medicine gets metabolized, a chemical reaction changes its molecules. They break apart and may recombine to form new substances. Metabolism happens in many ways. In hydrolysis, an enzyme breaks apart the drug molecule and a water molecule. The hydrogen from the water molecule combines with one part of the broken drug molecule, and the oxygen combines with the other part. One family of enzymes, called cytochrome P450, is especially important for processing medicines. Six of these enzymes handle approximately 90 percent of drugs.

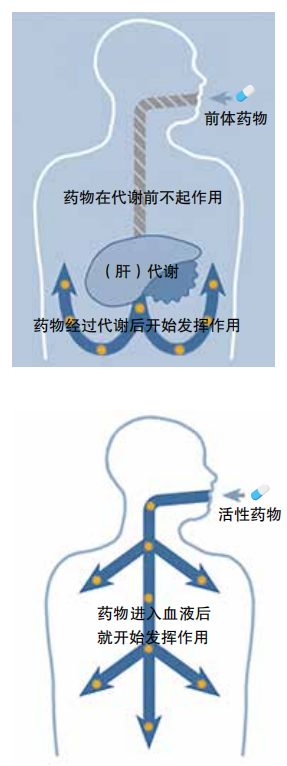

Usually, metabolism marks the end of a medicine’s life. It can no longer do its work. Depending on the type of medicine and the patient’s body, a lot of medicine will get metabolized on its very first trip through the liver. These molecules never get a chance to do anything in the body. So the medicine may not work.

Some medicines need to be metabolized in order to work. These are called prodrugs. They have no active effect until the body breaks them down. They aren’t as common as regular drugs. “I think you turn to the prodrug strategy when there’s something wrong,” Derek Rowe, a medicinal chemist, wrote in Science. “Maybe the active form of the drug isn’t well absorbed from the gut, or has too short a half-life in the blood, or doesn’t distribute to the right organs. ”

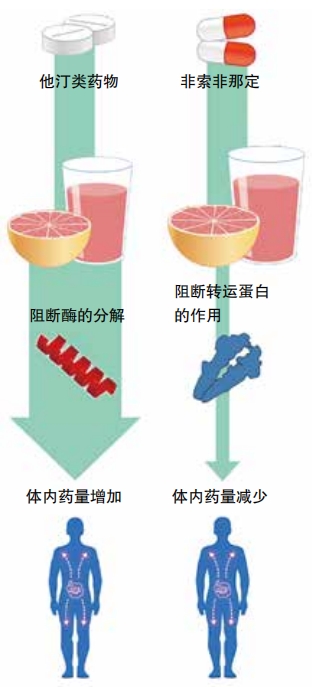

If a person’s body metabolizes a typical medicine too slowly, then too much of the drug may build up in their system. This can lead to side effects or even life- threatening toxicity. Some foods and vitamins mess up the metabolism of certain medicines. For example, one class of medicines, called statins, helps to lower the risk of heart disease. People on this medicine should avoid grapefruit or grapefruit juice. The fruit contains a substance that stops the body’s metabolism of statins. So too much of the drug may build up in the body.

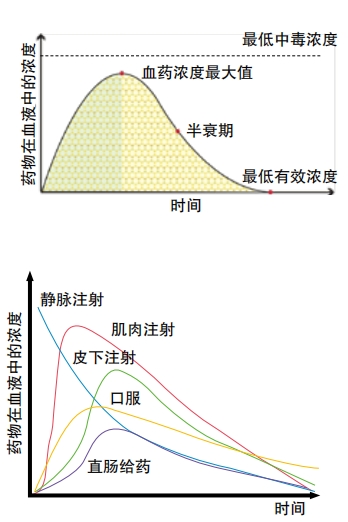

Tylenol reaches its highest level in the blood about two hours after you take it. As blood carrying medicine circulates, more and more of the medicine gets metabolized. Gradually, the liver breaks it down into substances that dissolve in water, and the level drops. The half-life of a drug is the time it takes for the level of that medicine in the body to reduce by half. For Tylenol, that is between one and three hours. After approximately twenty-four hours, there will be no trace of Tylenol left in the body.

Down the Toilet

Everything that enters the body must leave! The remains of medicine, much like the remains of food, typically exit when you go to the bathroom. Pharmacologists call this step excretion. Metabolism typically transforms the molecules of medicines into substances that dissolve easily in water. That’s what happens to the Tylenol you took. It turns into water-soluble molecules. These molecules continue to circulate in the blood. When they pass through the kidneys, their water-solubility causes them to get filtered out of the blood and exit in urine. This is what happens to most metabolized medicines.

Bile is fluid that helps with digestion. It travels through the small intestine. Bile also carries toxins that need to be removed from the body. Those may include metabolized molecules of medicine. These molecules and any other toxins in bile enter the large intestines, where they form feces and are excreted. Other pathways of excretion include breast milk, sweat, saliva, tears, and more.

Molecules of medicine don’t always get metabolized before getting kicked out of the body. Sometimes, they exit in their original, active form. A drug in its active form may also escape the excretion process by sneaking across the membrane of the kidney, stomach, or intestines. From there, it can absorb into the bloodstream and travel around the body again. This process is called re-absorption.

However, the steps of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion don’t happen neatly in order. Soon after you swallow a pill, all of them start happening all at once, with more absorption and distribution at first and more metabolism and excretion later.

The Art of Dosing

Your headache felt better for a while, but now it has come back! Can you take more medicine? That depends on how much you took and how long it has been.

The art of deciding how much medicine to give and how often to give it is called dosing. The goal is to keep a fairly constant level of medicine circulating through the body. If the level drops too low, the medicine won’t do its job. If the level gets too high, the person may experience dangerous or even deadly effects. You may have heard that “the dose makes the poison. ” This means that most substances become poisons when very high levels enter the body. Pharmacologists call that sweet spot in between too little and too much medicine the target concentration.

All bottles of medicine contain dosing information. Regular strength Tylenol comes in pills that contain 325 milligrams of active medication. Adults can take two of these pills every four to six hours. But they should never take more than six in one twenty-four-hour period.

When the level of medicine in the blood needs to be more tightly controlled or if something seems to be wrong, doctors can check urine or feces. They look for traces of the drug to see how quickly the person’s body is metabolizing it. If needed, they can then change how much medicine they are giving or how often they give it. In some cases, doctors will give a higher dose of medicine the first time the patient takes it. This is called a loading dose. It allows the drug level in the body quickly reach the target concentration. The next time the patient needs medicine, he or she will take a lower amount, called a maintenance dose.

Pharmacologists also use the word bioavailability to talk about the percentage of a medicine that actually gets absorbed and is available to do the work in the body. This is because when you swallow a pill, some portion of the medicine does not get absorbed or make it to the correct part of the body, so the pill usually contains more medicine than would be needed.

In the future, medicine may be more individualized. Dosing may be far easier, and the chance of side effects or adverse reactions may be lower.