We love looking at art. We put it on our walls. We see it at museums. And if we’re inspired, we may even create it. What is it about our art experience that makes it so enjoyable? We can appreciate art as one of those things we do simply for a pleasurable experience—such as when we listen to music, watch a movie, or read a novel. For most of us, these activities capture our attention and spark an emotional response . Although our survival does not depend on such activities, our lives would seem so much less enjoyable without them.

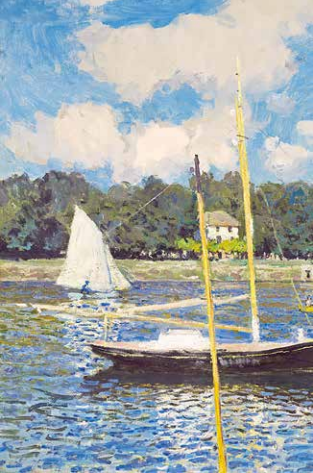

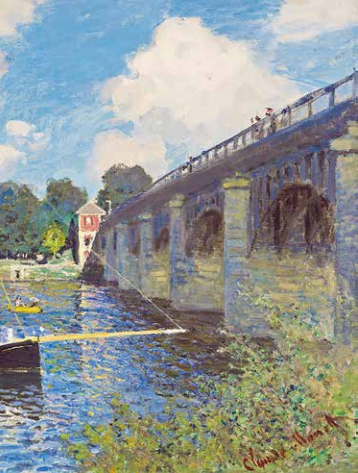

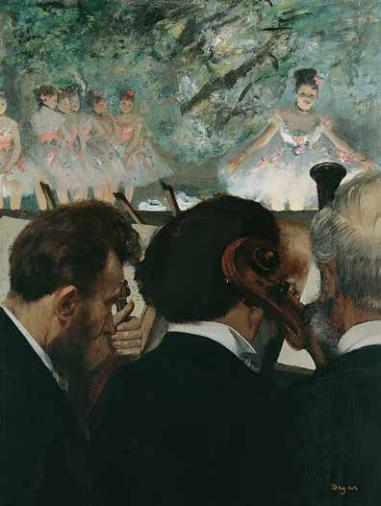

Often an art experience hits us immediately—as when we look at a beautiful painting. Consider The Bridge at Argenteuil by the French impressionist painter Claude Monet. Most of us develop a sense of peaceful serenity as we view this lovely painting. We can imagine ourselves on the river’s edge feeling a pleasant breeze blowing around us . We can also admire Monet’s artistry as he created a naturalistic scene but one that also displayed the sensual features of paint, as in his depiction of the reflections in the water as colourful splotches of paint. Also, we see the artist’s brushstrokes in his rendering of the bridge, boats, and foliage . These days, crowds flock to premier art museums around the world to view Monet’s paintings and others by his compatriots who initiated the impressionist style in the 1870s. But it wasn’t always that way. When these painters first presented their works, they were scorned and ridiculed. Critics at the time described their paintings as crude and lacking skill and said the works could hardly be called art. Now, in the same paintings, we see beauty, grace, and harmony. What’s changed?

We must experience art within the realm of our cultural and personal knowledge . To a large extent, what we know determines what we like. Nineteenth century European beholders were used to a very different style of art—one that depended on creating natural paintings that were like photographs—smooth depictions of scenes without any sense that paint was even being used. The intense brushstroke style used by impressionist painters was such a radical departure from what contemporary viewers were used to that these new works looked ugly and crude. Changes in our appreciation of art over time—within our culture and within ourselves—force us to consider the importance of our knowledge and prior experiences when we experience art. We all agree that our senses and emotions are engaged when we look at art, but we do not readily acknowledge the contributions of cultural influences and personal memories toward our appreciation of art.

There is a common saying about art—beauty is in the eye of the beholder. I would rephrase this and argue that beauty is in the brain of the beholder.

When we respond to art it is our psychological makeup that drives the experience . Based on our general dispositions, prior experiences, and how we may happen to be feeling at the time, a work of art may elicit that “wow” feeling as our senses, thoughts, and emotions are heightened to the max . I remember having this reaction in Florence, Italy, when I saw Michelangelo’s statue of David for the first time. Other times, we might experience a more subtle sense of beauty or peacefulness—as you might while viewing Monet’s The Bridge at Argenteuil.

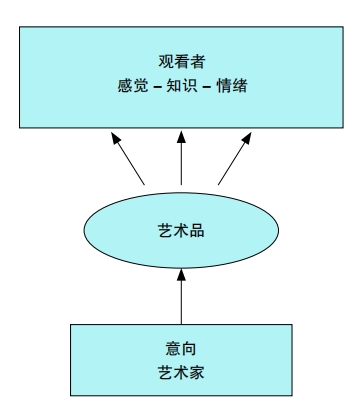

The diagram offers a way to view our art experience as a form of communication between artist and beholder . The artist creates an artwork with the intention of eliciting a response . The artwork is viewed by the beholder who considers how it drives sensation, knowledge, and emotion. I call this framework the I-SKE model of our art experience as it describes the reliance of the artist’s intention to create an artwork and three principle functions of the beholder’s experience—sensation, knowledge and emotion.

Some art experiences rely more on one of these functions than others. Classical artworks have tended to drive our sensations and emotions directly as we are often struck by the beauty or elegance of them. From the beginning of the 20th century, artists began to experiment with abstract paintings and to question the very meaning of what “art” could be. These artists downplayed the sen-sory and emotional qualities of their works and made us think and use our knowledge about what art is supposed to be. These days, artists go even further. At a contemporary art museum you might be presented with a canvas that is completely white. You might ask yourself, “Is this art?” Such a work might have little to offer with respect to sensations or emotions, but you might consider how it drives your knowledge—what is the artist trying to say, how is this work different from my past experiences of other artworks? Whenever we confront an artwork—be it a traditional work, an abstract painting, or a contemporary installation—we should consider how it drives our psychological experience completely, from our sensations to our emotions and on to making us think.

We don’t start from a “blankslate” when we look at art as we are always drawing on world knowledge, cultural influences, and personal memories. As such, we might think that our art experiences are so unique that there is no such thing as a universal sense of beauty. It turns out, however, that we as human beings have an abundance of shared knowledge and experiences . For example, everyone had a childhood, develops personal relationships, grows old, and ultimately will experience death. We all know that fresh air, clean water, and healthy food will enhance our survivability and that disease, tainted water, and rotten food will diminish it. These universal facts of life influence what we like.

When asked what color we prefer, most say blue or green—colors that represent fresh air and healthy foliage. Few would prefer the brownish hues of vomit or a putrid swamp . Moreover, most of us would generate the same emotion when viewing a painting that depicts a flirtatious scene between two lovers or an elderly mother on her deathbed. Likewise, most would garner a sense of relaxed peacefulness when viewing a painting of a pristine forest or tropical beach.

There is also a universal sense of physical beauty with respect to the human body. When people are asked to rate the attractiveness of a set of faces, they all tend to select the same ones as attractive (and unattractive). What makes a particular face attractive? One feature is symmetry—the degree to which the left and right sides match. All faces are to some extent asymmetrical, with perhaps a nose curved to one side or eyes that are not quite the same size or shape. Many of these are natural occurrences though some can be attributed to birth defects or disease. In these pictures, the two faces on top are straight photographs of individuals, whereas the bottom ones were digitally modified so that the left and right sides of each face are perfectly symmetrical. Note that no matter how attractive you think the actual faces are, both are made more attractive through symmetry. As a way of avoiding individuals with possible defects or diseases, evolution has molded our brains to be attracted to facial symmetry.

The experiences and knowledge shared across all humans have led us to a general consensus about what we like, such as preferred colors, pictorial scenes, and faces. On top of these general preferences are cultural and personal experiences that can modulate or alter these basic facts of life. Cultural influences are based on shared experiences determined by geography, political disposition, religious belief, or other group affiliation. These influences shape what we like and dislike about the world. Social psychologists have investigated how culture affects the way we perceive, think and feel. In a study published in American Scientist, 2000, Chinese and American individuals watched a video of five fish moving together. Suddenly four of the fish stop while the one in front continues moving. When asked about this video, Chinese individuals often described the front fish as an outcast who has been pushed out or ostracized by the others. Americans described the front fish as boldly making its own path and leading the others. Psychologists point to cultural factors that drive this difference in viewpoint. Since antiquity, Eastern philosophies, such as Confucianism, have reinforced collectivist views wherein group concerns supersede the concern of any individual. American culture rewards an individualist view in which the lone warrior, such as the Western gunslinger, is praised for moving forward and fighting the wrongs of a group.

On top of world knowledge and cultural influences are personal memories that shape what we like. Personal experiences may override preferences shared by all members of the human race or by those with your cultural background. You may like a yellow-brown color that was the color of as favorite stuffed animal even if most people find the color repulsive. You may abhor a painting of a lush green forest because you were once lost in a similar environment. It is important to think about our art experiences as driven by knowledge that we share with others and also by personal knowledge that may make our feelings about an artwork quite unique. Whenever you encounter an artwork that you like (or dislike), you should ask yourself what about the artwork generated your emotional response . Did I understand what the artist was communicating? Did it change my view of the world or reinforce cultural feelings? Was it personally meaningful?

An artwork may be about the human condition, about our society’s plight, about the artist’s personal experiences, or even about the making of art itself. When we confront an artwork, we should ask what story is being told. If a painting depicts a naturalistic scene, such as a land – scape, still life or portrait, we can identify objects within it and try to derive meaning in the way the scene is put together . If it is an abstract painting, we may consider how lines, colors and shapes suggest or symbolize real world objects, though in many instances it is better to leave the abstractions as such and consider what emotions are evoked by the abstract patterns and forms—not unlike appreciating nonvocal music . Whether an artwork is naturalistic or abstract, every picture tells a story, and it is up to the beholder to develop an understanding of it.

For many, the essence of an art experience is to invite an emotional response . On occasion, you might be lucky enough to get that “wow” feeling when sensations, thoughts and emotions are at their highest. This experience can even influence us physically, sending chills down our spine, giving us goose bumps or making us weep. By evaluating your sensations, thoughts and feelings, you may generate other emotional responses to art, such as awe, wonder, beauty and peacefulness. These days, artists may even try to instill negative reactions, such as anger or disgust. Invite art experiences by going to an art museum, checking out wall decorations at businesses and considering things that friends put up on their walls.

In truth , we generate a kind of art experience whenever we ask ourselves: “DoI like it?” We may ask this question while watching a movie, reading a novel or hearing a new song. We enjoy some things because they spark our senses or excite our emotions. Other things make us think. You may see how your cultural upbringing and personal experiences drive such preferences.

By considering the psychological makeup of our art experience—that is, how sensations, knowledge and emotions drive this experience—we can gain a better understanding of ourselves and how we interact with the world around us.