A Mystery Solved

Everyone can see that, from birth through adolescence, humans get taller and their bones get longer. And then all th at stops around the end of the teen years. In the past, the mechanism of growth was a mystery. In the fourth century, there was a common belief that children’s natural character was hot and liquid, partly because of the blood that went into their creation. Thus, a physician to the Roman emperor believed that children grew because of their excessive heat. Twelve hundred years later, it was understood that food provided the material that allowed growth. A French physician, however, pointed out that even when sick children didn’t eat, they continued to grow.

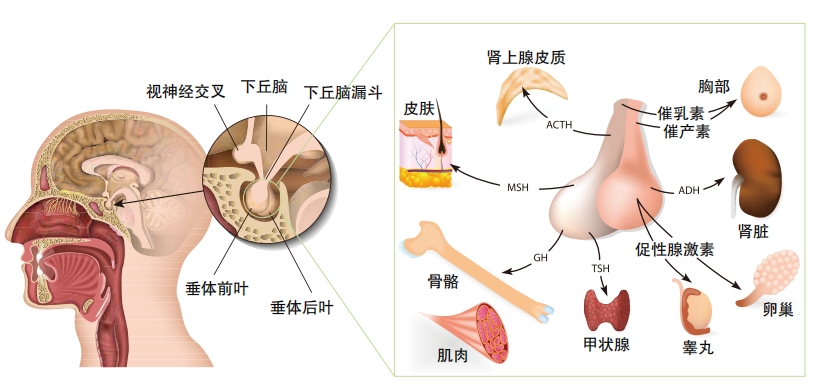

In the late nineteenth century, the idea took hold that the secretions of one or more organs were responsible for growth. A review of all reported cases of acromegaly, a condition in which the bones of full-grown adults continue to grow unnaturally, found that all the cases involved an enlarged pituitary gland. Until that time, scientists had considered the pituitary gland to have no or little function in the body. A few years later, early in the twentieth century, neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing began referring to “the hormone of growth,” which he surmised had something to do with the pituitary gland. Then, in 1921, Herbert Evans and Joseph Long injected extracts from a cow’s pituitary gland into rats and the rats became gigantic . With that experiment, they confirmed the role of the pituitary gland in promoting growth.

By the 1950s, Cho Hao Li and Harold Papkoff had found a way to extract human growth hormone from the pituitary glands of cadavers. It was a painstaking process that produced limited supplies for treating young people who failed to grow normally. Finally, in 1985, it became possible to produce growth hormone using recombinant DNA technology. There is now an unlimited supply.

How Do We Grow?

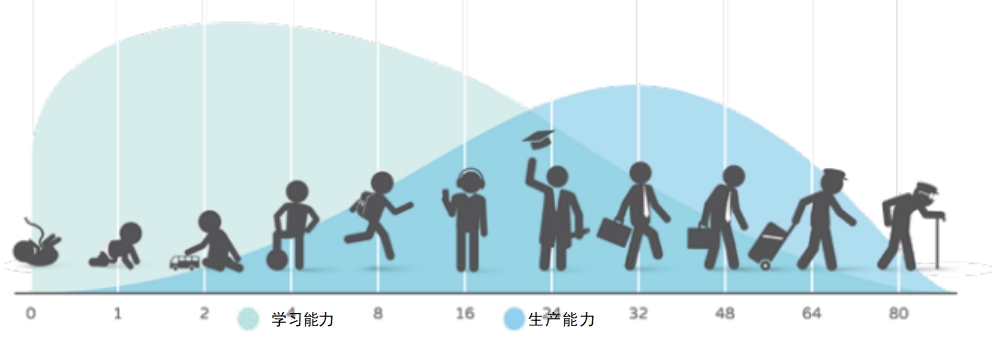

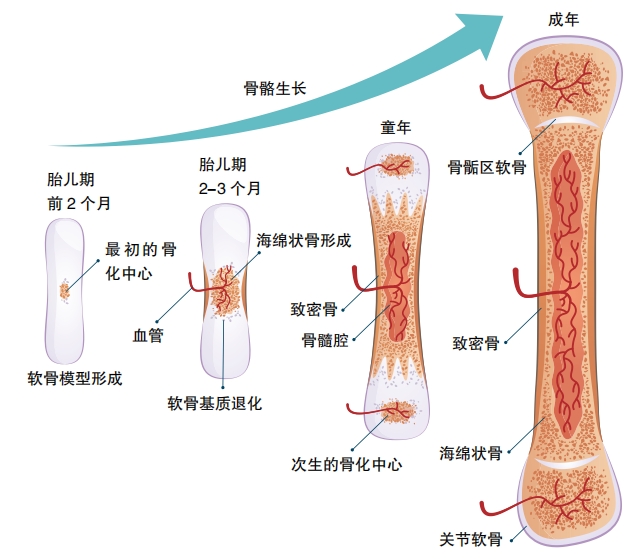

Humans experience their fastest period of growth before they’re born. A cluster of cells divides repeatedly, the cells differentiate into specialized tissues and organs, and, almost miraculously, a fully functioning baby develops . After birth, though children continue to grow, the speed of growth is not as great. Then, at puberty, there’s another growth spurt that continues until the adolescent is sexually mature. At this point, our genetic program is satisfied. We can reproduce, and no further growth is necessary.

During these periods of growth, our bones get longer because bone cells multiply at the growth platese piphyses— of bones . Hormones play a significant role in making this happen . When puberty begins, growth hormone and thyroid hormone are joined by sex hormones—both estrogen and testosterone are present in girls and boys , the difference is only in ratio of these hormones . When puberty ends, the epiphyses fuse, the growth centers of the bones can no longer respond to hormones, and growth stops.

The pituitary gland secretes considerably less growth hormone in adults than in young people, but it continues to have a role in healthy aging.

Biological Aging vs . Chronological Aging

We know how many years we have lived (our chronological ages), but what about our biological ages (how rapidly our bodies are aging)? People die at different ages . For decades, biologists have tried to find biomarkers in the blood or tissues that measure how far along a body is in the aging process . Knowing someone’s chronological age isn’t enough.

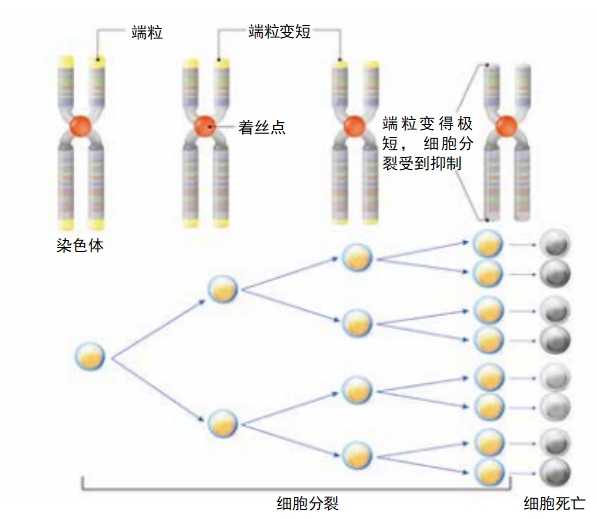

In the 1980s, Elizabeth Blackburn and two colleagues discovered that the caps on our chromosomes — telomeres—have to maintain a certain length for cells to continue to divide. Each time a cell divides, the telomeres get shorter. The discovery seemed to promise a way to gauge disease and to determine how likely a person is to die early. Telomere length might help a doctor consider a person’s risk for some age-related diseases, some of which might lead to an early death. But study results are too inconsistent for telomeres to be considered a good biological age marker.

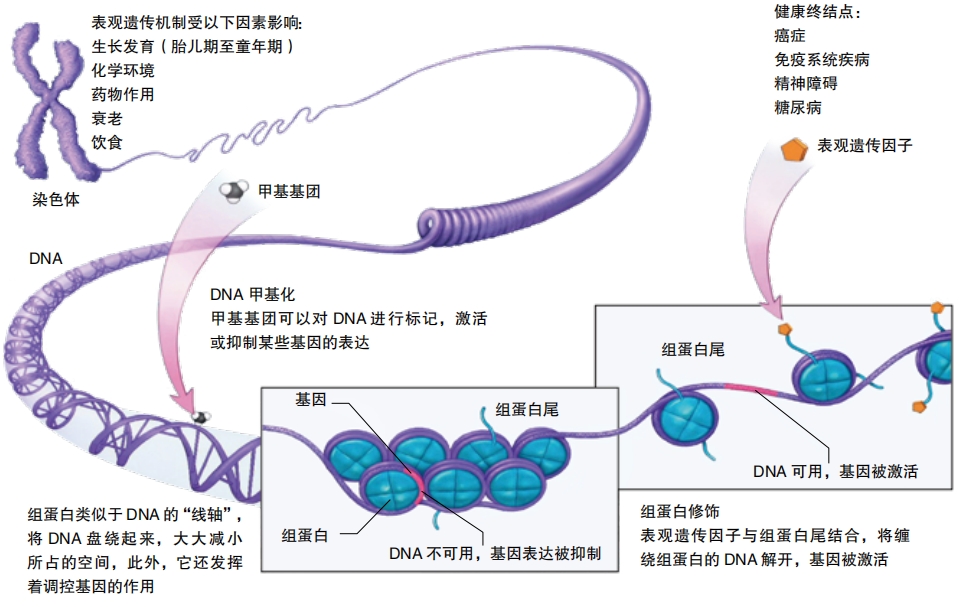

As a young man in Germany, Steve Horvath vowed to devote his career to finding a way to prolong healthy human life. He’s now a geneticist in California, and for more than a dozen years, he’s been working to develop an aging test. He began by looking for changes in gene activity that occur in a predictable manner over a person’s life. Horvath thought, “Since all cells contain DNA maybe we can track chemical modifications of the DNA molecules—epigenetic modifications.”

Epigenetic changes alter the physical structure of DNA without changing the DNA sequence itself. All the cells in the body contain the same DNA, but they look and function very differently. A skin cell and a red blood cell are not at all similar. That’s because epigenetic modifications cause some genes to turn on (be expressed) and others to turn off. In muscle cells, the gene to make muscle protein must be turned on . But in eye cells, that gene is turned off and genes for sight are turned on.

One important e pigenetic modification is methylation, a process in which a methyl group attaches to a DNA segment and prevents certain genes from being expressed. Methyl groups are added to DNA from birth to death.

An Epigenetic Clock

In 2011, Horvath was part of a team that analyzed methylation patterns in DNA from the saliva of sixty-eight adults. The team wondered whether they could use the patterns to predict age. Horvath looked at how many cells in a drop of saliva had methylation at two particular sites on the DNA. The pattern correlated with the chronological age of the participants 85 percent of the time.

Horvath explains that methylation on DNA is like rust on a car. By looking at how much rust has accumulated on a car, you can guess its age. Methyl groups accumulate on DNA at a predictable rate over a whole lifetime. If you know the rate, you can guess a person’s age.

He then tried analyzing methylation patterns from brain tissue and blood. The results were even better. Using larger data sets and more sites on the DNA, he was able to predict the chronological age of the donor 96 percent of the time . When his results were published in 2013, other scientists began applying Horvath’s program to their own data sets. The accuracy went up to 99.7 percent.

Depending on the environment a car operates in and the care its owner has taken of it, the car may have more or less rust than its actual age would indicate. The same is true of methyl group accumulation on DNA. Horvath found that blood from some donors had more methylation than the average for their age. This could indicate a slightly elevated risk of death or disease.

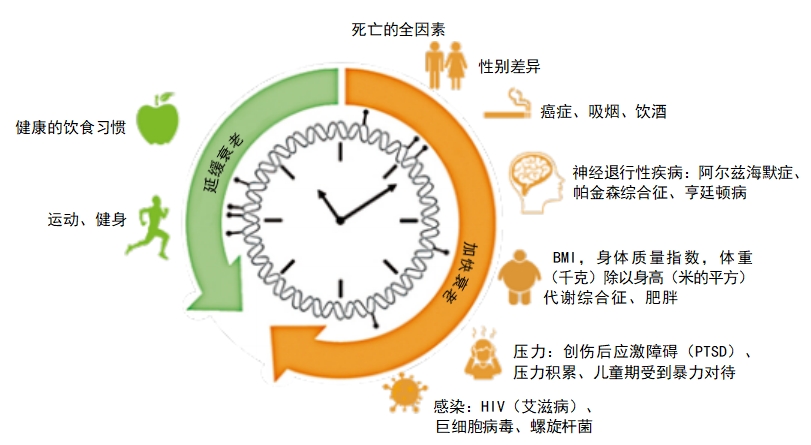

A new kind of epigenetic clock that can detect smoking was discovered in 2018. If a person smokes, this clock shows they have a much older biological age. This is consistent with the well-known risk of a smoker’s dying early.

This epigenetic clock is a biomarker for a biochemical process that plays a role in aging. Being able to determine a person’s biological age is only the first step in Horvath’s original vow to find a way to prolong human life. His interest was not just in adding years to life but in adding years of health.

Slowing Aging

As a young biochemist, Cynthia Kenyon was curious about what caused aging. She says, “People used to think that aging was just something that happened, that you wore out like an old car .” She noted that bats lived for twenty years and mice lived for two years, but they were both mammals, similar in size, and not all that different. If aging was just something that happened, why didn’t it happen the same for everyone . In addition, she knew that “nothing in the cell just happens . Everything seems to be under some control. I thought maybe there was some kind of apparatus in the animal that could control the rate of aging in some way.” She knew the secret had to be in the genes.

She began exploring regulator genes, genes that control the activity state of lots of other genes. She chose Caenorhabditis elegans, a nematode, for her study. This small soil worm is about 1 mm in length and has a short lifespan, which made it perfect for longevity research. In the 1980s, aging research was widely considered a dead end for a scientist (watching things wear out would be boring), and Kenyon had trouble attracting people to work with her.

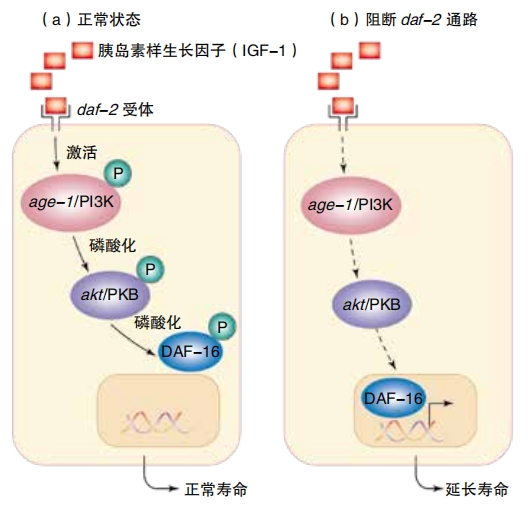

However, in 1993, Kenyon and a handful of team members had a breakthrough. They discovered that switching off a single gene—the daf- 2 gene—caused the worms to live twice as long as normal and to remain youthful and healthy throughout their extended lives. “That was really amazing,” Kenyon says. ” You’d just never think it was possible that you could take out one gene and keep an animal young. You’d think, well, you have to fix the skin, you have to fix the bones, you have to fix everything. Then you change one gene and everything’s fixed. It fixes itself for you, all at once. ”

daf-2 controls the activities of about one hundred other genes, ones that help to prolong life. Some of them are antioxidant genes, preventing cell damage ; some of them are antibacterial genes, protecting against infections; and some are metabolism genes, affecting how the body uses food. When daf-2 is turned on, it suppresses those protective genes.

Later, Kenyon and her team discovered another regulator gene that affects lifespan. Unlike the daf-2 gene, the daf-16 gene triggers genes that increase lifespan. With daf-2 turned off and daf-16 turned on, Kenyon’s team caused C. elegans to live six times longer. Instead of the normal 20 days, they lived for 125 days. That’s like a human living 450 years. Imagine visiting a relative who was alive during the Ming Dynasty!

This astonishing discovery brought a lot of attention to the field of aging research. Many other scientists joined the search for a means of lengthening human lifespan without the diseases of aging. They refer to this as health span.

When daf-2 is turned on, it creates receptors that allows cells to respond to hormones. In humans, these are insulin, the hormone that controls blood sugar, and an insulin-like growth factor,IGF-1. Kenyon’s work showed that when they lowered the production of insulin and IGF-1, the worms lived longer. Because our bodies produce insulin when we eat sugar and other refined carbohydrates. It’s reasonable to think that eliminating those from our diet will help us live longer.

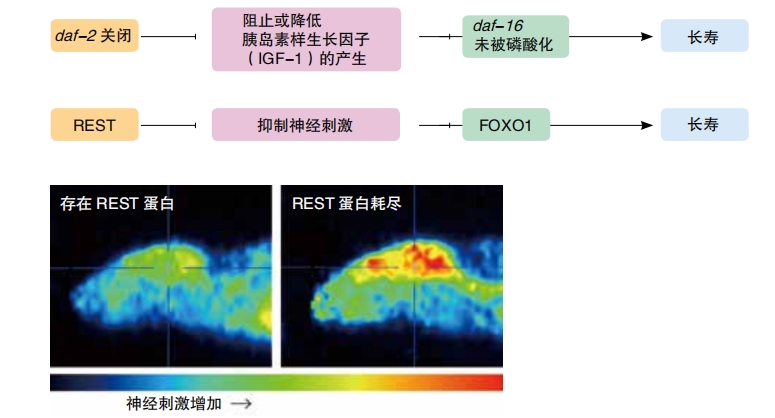

Recently, Bruce Yank ner and his colleagues reviewed data from donated human brains that they’d studied some years ago . They had been interested to see how gene expression changes over a lifetime. They recognized that many of the changes were caused by a protein called REST . REST is active in the brain before birth, repressing genes controlling neurons until the brain is ready for them. They discovered that REST is also active in the aging brain. It interferes with the production of proteins that are involved in exciting neurons to fire. Interestingly, the brains of the people who lived the longest had low levels of proteins that take part in the excitation. The REST protein really does encourage a more restful brain.

To test the association, Yankner’s team compared brain firing activity in the long-lived C. elegans with that of the worms who hadn’t had the daf-2 gene turned off. The worms with daf- 2 turned off had very little neuronal activity. When the researchers deprived these worms of the REST protein, the expected increase in life span disappeared.

The take away from this is that overactive neurons may do damage. Perhaps healthy aging requires maintaining a proper balance. In the future, there could be drugs that quiet the overexcitation. In the meantime, we might need to change our diets if we want to live longer.

Can We Reverse the Aging Process?

So maybe we can slow down the aging process, but can we actually reverse it? Make our kidneys younger? Our hearts youthful? There’s hope that that can be accomplished. Scientists in Luxembourg identified a molecule in the mouse brain that keeps neuronal stem cells quiescent in aging mice. The scientists were able to inactivate the molecule, and the stem cells began to reproduce. For now, they’re hopeful that their work will result in therapies for degenerative brain diseases, but they think there’s potential for applying it to other organs.

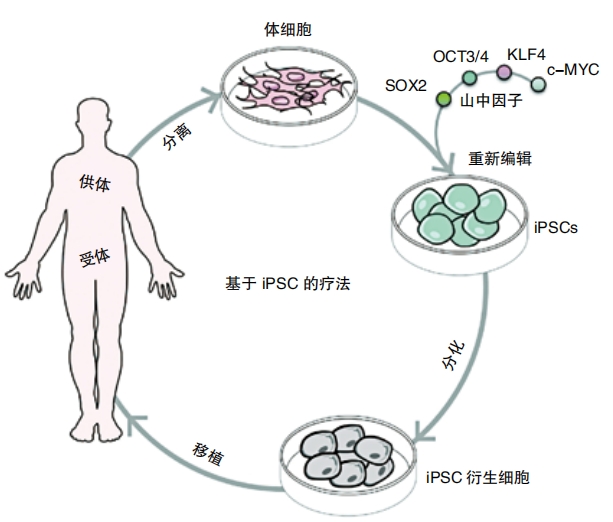

Tapash Jay Sarkar and his team at Stanford University in California have designed a method to reverse the errors that accumulate in the epigenome. They have used powe rful agents (Yamanaka factors) in stem cells to reprogram a cell’s epigenome to an embryonic state. There are cancer risks in taking a cell that far back. However, they found that using small amounts of the factors for a short time could return a cell to a youthful state without it losing its identity. They have taken cartilage cells from patients with osteoarthritis and treated them with a low dose of Yamanaka factors . After treatment, the cells no longer produced an inflammatory condition.

It appears that scientists are making progress on reversing age- related damage to individual organs and tissues . But reversing the age of the whole body is a different matter. But last year, in a small trial in California, nine volunteers took three common drugs for 12 months. The drugs were growth hormone and two diabetes medications . At the end of the trial, Steve Horvath measured their biological ages using his epigenetic clock. They had shed an average of 2.5 years off their biological ages as measured at the beginning of the trial. That was startling even to the researchers. Much larger trials will be needed before the scientific community will embrace the results.

Controlling and extending the human lifespan seems within our reach. Extending our lives even by a few years could be of great benefit if they can be healthy years. Cynthia Kenyon doesn’t see any reason why we couldn’t live six times as long as we do now, just like her nematodes. Are you ready to greet the twenty- fifth century?