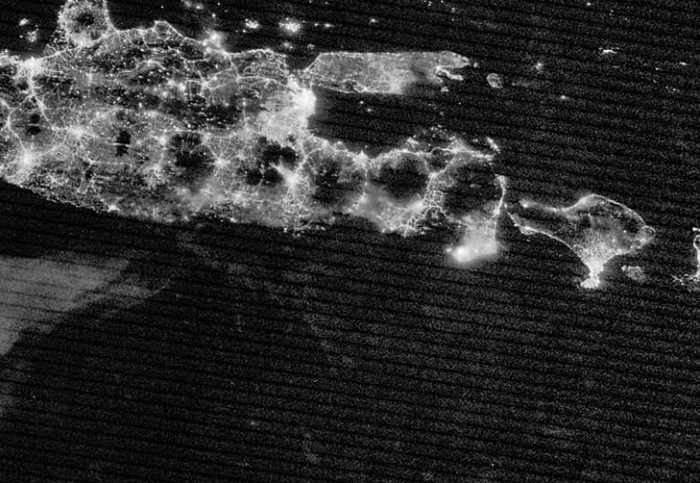

Places where life can thrive vary widely on planet Earth. Scientists find the greatest diversity in rainforests with abundant water and mild year-round temperatures.

In contrast to Earth, somewhere like Mars seems like a bleak wasteland. With an atmosphere that’s about 100 times thinner than Earth’s, the planet surface can’t hold in heat well. A summer day at the Martian equator might get up to 20℃ at noon, but sink below -70 ℃ at night. Temperatures at the poles can be as cold as -125℃ . And even Mars seems more welcoming than some other parts of the solar system or the dark void of space.

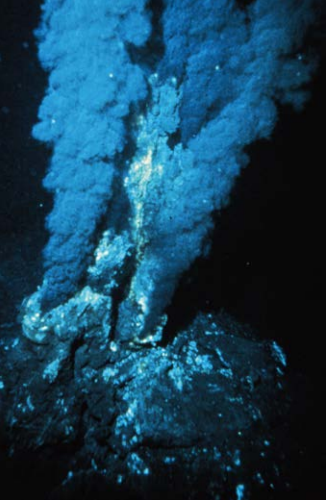

Yet Earth wasn’t always the way it is today. And even if humans can’t live somewhere on Earth, other species might eke out a living there. Scientists have found life deep on the dark ocean floor, living near deep gas vents. They’ve found life in salty lakes. Some life likes acidic conditions. Other life likes icy glaciers, hot springs, or other places with extreme temperatures.

“We call these things extremophiles,” says Victoria Petryshyn. She’s a geologist in the Dor ns ife Environmental Studies Program at the University of Southern California in the United States. From our viewpoint, extremophiles live in harsh conditions.“To them, it’s the environment that they like, their happy place,”Petryshyn says.

Looking Far, Far Back

You probably wouldn’t recognize early Earth as the planet we live on today, Petryshyn says. “The sun would only have been about 70 percent as bright as today,” she notes. And the planet might have been warmer than now but not super-hot.

“There would have been a lot of carbon dioxide and methane,” she adds. Some level of carbon dioxide was necessary to warm up the planet enough so that it wouldn’t be a frozen mass. And things were “just constantly running into the Earth early on. ” Water likely came from icy comets. And meteorites likely carried other ingredients for life, such as nucleic acids and building blocks for proteins.

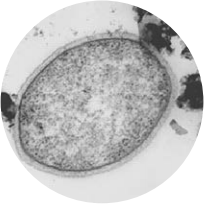

We don’t exactly know how life began on Earth. But by 3.7 billion years ago, single-celled organisms had apparently begun in little ponds. Scientists know that from studying very old rocks and finding a type of carbon molecule that living things make. Other evidence of early life comes from stromatolites. Those rocks have crinkly patterns in them, and the oldest ones are roughly 3.5 billion years old.

“We think life must have formed this, because this pattern doesn’t easily happen in nature,” Petryshyn says. Perhaps microbes formed a sticky mat called a biofilm that trapped sediments over time. Or maybe the microbes’ metabolism changed the water chemistry to make some minerals fallout of solution. Rock samples from elsewhere in our solar system might someday reveal a record of similar signs of life.

Life-forms that use oxygen to do photosynthesis came somewhat later on Earth. They too would have left various biosignatures—evidence that something alive had been there.

Going to Extremes

Charles Cockell is an astrobiologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. There, he studies the possibility of life beyond Earth. Among other things, he looks at how species live in extreme environments. After all, he says, compared to what we’re used to, “most environments in space are quite extreme. ” Think super cold or having less gravity or high radiation levels or little atmosphere, perhaps with gases we can’t breathe. Or there could be all of those conditions plus more. So is an environment habitable or not? It depends on what you’re talking about.

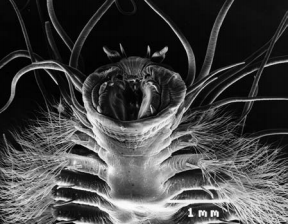

Complex organisms that can survive extreme conditions have evolved remarkable adaptations. Tiny brine shrimp are the largest animals that can survive the high salt content of the Great Salt Lake in the United States. The covering on their bodies keeps out most water and the salt in it. The shrimps’gills and special neck glands filter out any excess salt that otherwise gets in.

Methane ice worms thrive in solid mounds of methane, called gas hydrates, along the ocean floor. Other types of deep sea worms thrive near methane gas vents. The animals seem to live on bacteria that can get energy from the methane.

“Microorganisms on Earth have demonstrated tolerance to an extensive set of conditions, including high and low temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and many more dimensions,” adds astrobiologist Edward Schwieterman. He’s at the University of California, Riverside, in the United States.

Tiny bacteria have also evolved unusual ways to fix carbon. That’s the chemical process of converting carbon from inorganic materials in the environment into a form an organism can use for energy and building body mass, Petryshyn explains.

Green plants do that through photosynthesis, where they combine carbon dioxide and water in the presence of sunlight to make sugar. People and other organisms use oxygen to strip electrons off glucose molecules. That lets their bodies get energy and build body mass.

But many bacteria don’t need oxygen. Cockell explains, their chemistry can use things like iron, sulfides, or hydrogen to get the job done. That knowledge could offer clues for alien lifeforms’ survival strategy. Bacteria that can “breathe” iron in that way might also help people understand soil formation or mining on planets or moons. One of Cockell’s experiments in 2010 showed how some of those bacteria on Earth could play a role in the weathering of meteorites. Those are rocks from space that have landed on Earth.

Looking at other extreme environments

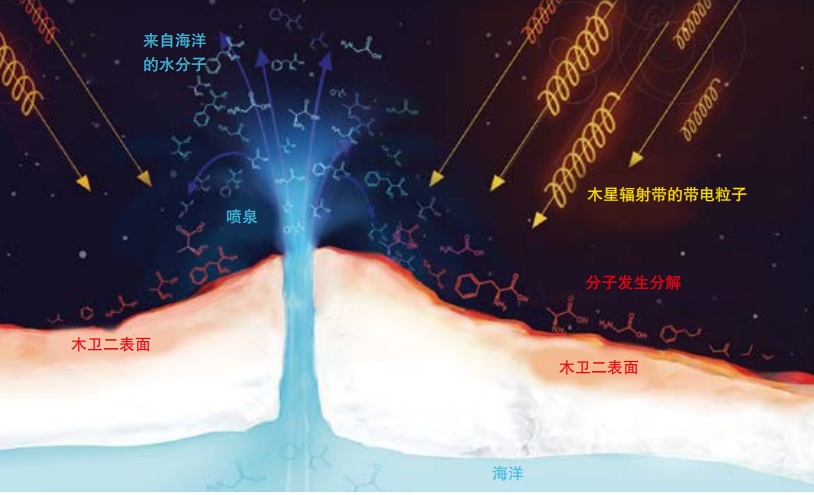

Scientists have not yet found any evidence of life on Jupiter’s icy moon, Europa. However, it seems that there’s an ocean underneath that icy shell. There’s also evidence of ongoing geologic activity, such as geyser-like releases of gases from within the planet and upwelling of its ice-covered ocean. To some researchers, that suggests conditions similar to the extreme deep sea environments in which some species survive on Earth. For those scientists, Europa is thus a decent bet for finding some form of life.

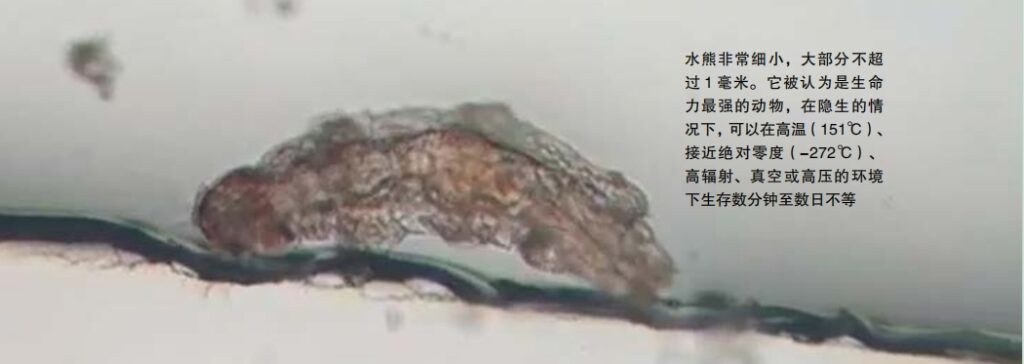

Tardigrades also suggest strategies for how some life forms might survive high-radiation environments, intermittent water and other harsh conditions on other planets or moons. Often called water bears, the tiny creatures have big heads, pudgy bodies, and eight stubby legs each. They need water for the active part of their lives, so many species hang out in mosses, lichens, and algae. Some tougher types live in Arctic and Antarctic regions . Scientists even sent some tardigrades into space as an experiment. They survived the radiation and vacuum of space.

The tardigrades’trick: they shrivel up into a tiny dried husk called a tun. A special proteins protect the animals during harsh conditions. When those conditions subside, the animals become active again. A team at the University of California, San Diego, used chemistry analysis to show how the protein, called Dsup, works. Their report was in eLife in October 2019.

“The scope for habitability is large, but not infinite,”Schwieterman adds. Parts of the Dallol hydrothermal pools in Ethiopia are an example, he notes. The conditions are just too acidic and too salty.

In short, there are some minimum requirements that life needs. You need some source of energy . You need sources of carbon, hydrogen, and some other elements to build up body mass and proteins and to do different chemical reactions. And you need liquid water to let metabolic and other chemical reactions take place. Cockell explains some of the physics and chemistry behind those requirements in his 2018 book,The Equations of Life.

Launching Life into Space

An experiment with tardigrades launched some into space. They came back and survived. But tardigrades aren’t the only extremophiles people have sent into space. Among other things, astrobiologist Charles Cockell at the University of Edinburgh looks at how microbes extract energy and nutrients from rocks. One of his projects sent microbes into space as part of experiments to be done on the International Space Station.

Other projects since 1960 have sent a wide range of species into space and brought them back. That first flight included dogs, a rabbit, mice, rats, and fruit flies. Plants, fungi, bacteria, and other organisms have also gone up, along with people.

Coincidentally, Cockell adds, humans have also sent some microbes into space unintentionally. The microbes hitch rides on spacecraft. But we don’t know if any survived indefinitely on another planet or moon without a protected habitat like a pressurized spacecraft.

Chris McKay is a scientist with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in the United States. He wrote the limits of life in a 2014 article for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Below about -15 ℃ , for example,it’s hard to have any liquid water. And above roughly 122 ℃ , most proteins won’t be stable. Cells also wouldn’t tolerate more than 1,100 times Earth’s regular atmospheric pressure. And too much radiation would be disastrous for an organism’s genes. McKay reported radiation limits of about 50 grey units per hour for a continuous dose. The maximum short-term dose would be around 12,000 grey units, although there might be some exception for an organism in a dry or frozen state. (Remember the tardigrades!)

Mars and Eu ro pa are good possibilities for life in our solar system. Schwieterman, Cockell and others hope

they might one day find signs from planets outside our solar system. The work would focus on the habitable zones around nearby stars,where a planet might have stable liquid water and a connection between the atmosphere and places where anything might live. And scientists might someday spot biosignatures from planets in other solar systems as well.

“Using spectroscopy, the splitting of light into its component colors, future observations would be able to infer the presence of oxygen or other biological gases in the atmospheres of those planets,” Schwieterman explains. “It is incredible to think that within our lifetimes we may be able to determine whether life is common or rare in the universe. ”

“We should never give up looking,” adds Cockell. Whether we find life or not, he says, “we’re going to learn something profound about ourselves. ”