Whenever the word “genius” is used, a small but magnificent group of names usually follows . Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Raphael, Beethoven and Mozart are the automatic choices . For the modern era, two giants stand above all others: Albert Einstein and Pablo Picasso . They are in so many ways connected, especially because both of them redefined the way we consider the world we live in and both of them had brilliant new concepts of space. For Einstein, it meant the universe and man’s place in it were suddenly better known. For Picasso, the breakthrough was cubism, a way of looking at objects in space that was completely unlike any artistic vision before.

Picasso’s mastery is famous. The inventiveness of his dancing brush (or pen) created a seemingly endless supply of images . He once said to his friend Andre Malraux, “They keep coming and coming! Like pigeons out of a hat.”

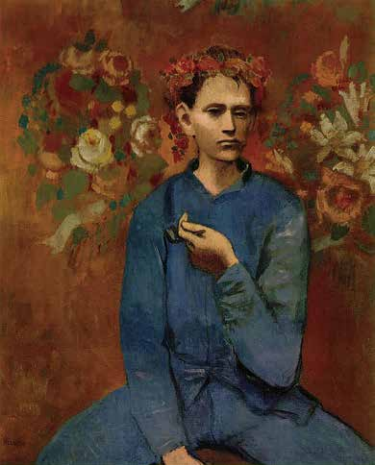

Born in Spain, the son of an art teacher, he surpassed the drawings of his father and his fellow teachers as a child. Picasso moved to Paris, where the action was, in 1899. His early realist paintings, especially the Blue Period (1901-1904), were fantastic displays of his technique.

He quickly became the center of the bande a Picasso— “Picasso’s little band” —a club that met at the café called Le Lapin Agile. The members shared a fierce commitment to the avant-garde . They changed forever the way artists painted in every genre: still life, portraiture, landscape . The major change was the shift to cubism, which broke the line that bounded forms (such as the human figure or the outline of a vase or table) and presented the world not just in three dimensions but in four (because the image was also altered by the passage of time, as the artist’s point of view moved from the front to the side to the back). Picasso’s genius was to put all of this on a two-dimensional plane, the canvas.

To be in Paris in Picasso’s time was to paint at least partly in response to the stimulus of his presence. Many artists were in touch with the master through mutual studio visits, by sitting elbow to elbow with him at the marble disk of a café table, or by standing in the corner sharing snippets of gossip at an opening.

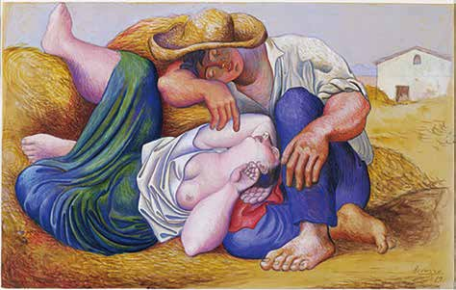

Picasso married a ballet dancer, Olga, and painted her in an old master style, not in cubist style, giving her the realist beauty of a portrait by Raphael or Ingres.

In any contest, Picasso comes out the winner. Picasso “competed” with his predecessors, such as El Greco, Delacroix, Courbet, and Velazquez, not to mention such contemporaries as Matisse, Modigliani, Leger, and de Chirico . He also transformed the tribal arts of Africa and prehistoric cave paintings into something modern and uniquely his own. Picasso once had a conversation about this with the great French cultural expert André Malraux.

Picasso: When people want to understand Chinese, they think: “I must learn Chinese,” right? Why don’t they ever think that they must learn painting?

Mal raux: You know perfectly well why. They think that since they’re capable of judging the model, they can also judge the painting. They’re only just beginning today to tell themselves that a painting isn’t always a copy of the model. Because of you, and cubism, and the arts they’re now beginning to discover—the arts of the early ages, the tribal arts, etc. Those don’t copy models either—or at least not very much….Nowadays, the nonartists who visit the Louvre are the people who admire whatever makes paintings into good likenesses; the artists are those who admire everything that doesn’t make them into good likenesses.

Picasso: People say, “I have no ear for music,” but they never say, “I have no eye for painting.” I know, in some vague way, what I want, like when I’m about to start on a canvas. Then what happens is very interesting. It’s like a bullfight: you know, and you don’t know.

Picasso was painting rapidly and masterfully up until his death, by influenza, at age ninety-one. The world of art is still taking the measure of his presence, like a mountain next to a desert.