At the end of the story Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl, the eccentric inventor and candy – maker Willy Wonka takes young Charlie Bucket into a glass contraption that he calls a Wonkavator. It bursts through the roof of the factory and flies them out over the city. Willy Wonka says, An elevator can only go up and down, but the Wonkavator can go sideways, and slantways, and longways, and backways, and squareways, and frontways, and any other ways that you can think of.

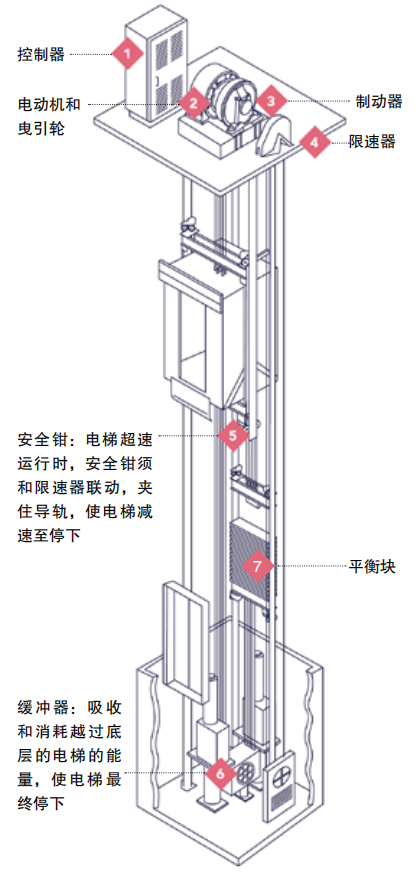

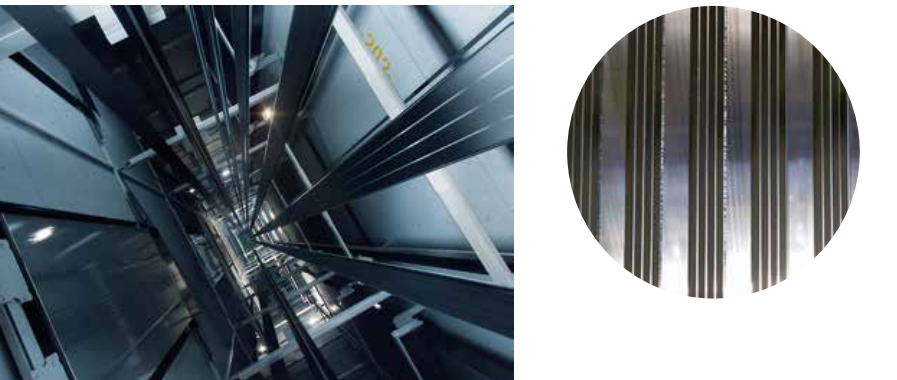

Real elevators, of course, can’t escape their buildings and fly. And most still only go up and down. The most common type is a rope elevator. A motor at the top of the elevator shaft winds a cable around a pulley in order to pull the elevator car up and unwinds the cable to lower the car down. As the car goes up or down, a heavy structure called a counterweight goes the opposite direction. This keeps the system balanced.

Elevators of various kinds have been around since ancient humans used rope and pulley systems to lift heavy loads. In 1852, Elisha Otis invented a safety brake system that would stop an elevator from falling if its rope snapped. When the rope was tightened, the tension pulled a set of teeth away from the walls of the elevator shaft on either side. But if the rope broke, that tension disappeared, and the teeth gripped the edges of the shaft, stopping the elevator within seconds. Soon, elevators became commonplace, allowing buildings to grow taller and taller. Today, engineers are building elevators with new abilities that might make even Willy Wonka smile.

High Speed Elevators

The first passenger elevator traveled at just 12 meters per minute. That’s less than 1 kilometer per hour, much slower than most people walk. A typical elevator today moves from around 8 to 35 kilometers per hour. That’s better than walking speed, but still slower than a car, bus, or train. New high speed elevators, though, take vertical transportation to the next level. In 2019, the company Hitachi broke a world record when one of its high speed elevators, installed at the Guangzhou CTF Finance Center in China, reached a speed of 75.6 kilometers per hour. It traveled from the ground floor to the ninety-fifth story in just forty-two seconds. The elevators at the Shanghai Tower in China are almost as speedy. They travel at 74 kilometers per hour.

Powerful, highly efficient motors make high speeds possible. The cabins are also designed to be aerodynamic to help them slide through the air more easily. When people move up or down rapidly, though, they feel uncomfortable or sick as the air pressure changes. (Air pressure is highest close to the ground and drops as you go up.) If you’ve taken a flight on an airplane, you probably noticed your ears popping painfully during take-off or landing. To help with this problem, some high speed elevators have systems that adjust the pressure inside. These elevators must be air- tight. A barometer measures the pressure inside and a blower either adds air or removes air to keep the pressure changing at a comfortable rate.

The Ultra Rope

When Otis demonstrated his safety brake system, he used natural hemp rope to lift a platform. By the 1870s, elevator builders had switched to using much stronger ropes made of bundles of metal wires. Today, these cables are usually made of steel. Steel is very strong and durable, but it’s also heavy. The longer an elevator shaft gets, the more cable you need to lift a car from the bottom to the top. The cable needed for a 500-meter-tall elevator shaft weighs around twenty thousand kilograms! If you try to make an elevator taller than that, the motor will not be able to lift so much heavy cable. At the 829-meter-tall Burj Khalifa and many other skyscrapers, no elevator goes all the way from the bottom to the top. Separate elevators serve the floors below five hundred meters and the ones above that height. People must switch elevators in sky lobbies to travel between the bottom and very top floors.

A new material, named UltraRope, should make it possible to build elevators that go up to one kilometer high, twice as high as any elevator that exists today. UltraRope doesn’t look much like rope at all. At four centimeters wide and four millimeters thick, it looks more like a thin, flat belt. Each belt contains four tapes of carbon fiber set side by side and coated with a plastic material called polyurethane. Carbon fiber is lightweight but stronger and more durable than steel. Manufacturers make carbon fiber by forcing carbon atoms into a tightly bonded chain and burning off all non-carbon atoms. The strong bonds between carbon atoms give the light material its incredible strength. The new material also doesn’t rust or stretch over time.

A steel cable is seven times heavier than an Ultra Rope of similar strength. “That’s a tremendous amount of steel you won’t have to move around the building,” says Johannes de Jong. He is head of technology at Kone, the company that invented Ultra Rope.

The company has been extensively testing Ultra Rope for years in an old mine shaft in Finland. “We have done testing with different temperatures, we have done aging testing… we’ve done strength tests. You just name it, we have done it,” says de Jong. The material passed every test, and in 2013, a resort in Singapore became the first to use the material in its elevators. Construction workers are also installing Ultra Rope as part of the elevator system in Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia. The architects of this tower plan to make it the world’s tallest, but for now, it is still underconstruction.

More Elevator Cars, Less Space

Another problem with traditional elevators is that only one car goes up and down inside each shaft. To allow lots of people to travel at once, large buildings must include lobbies filled with elevators . The Empire State Building in New York City has 102 floors and 73 elevators. All those elevator shafts take up space that could’ve been used for apartments or offices. Even with all those elevators, workers in office buildings spend a lot of time waiting for a ride. In 2010, the company IBM added up all the minutes that all the office workers in major US cities spend waiting for elevators in one year. They got a total of ninety-two years.

One solution to this problem has been around since the 1860s . The paternoster is a form of elevator that works a lot like an escalator. A series of cabins without doors ascend and descend constantly, side by side, on a belt. Passengers simply wait for an open one, step on, ride as far as they want to, then step off. Of course, the lack of doors and the ability to jump off or on at any time aren’t exactly safe. Paternosters are not common today. And they come with warnings that they should be ridden at your own risk.

In 2002, the international company ThyssenKrupp invented the TWIN system. The new system allows two elevator cars to travel in the same shaft. The lower car carries people between the ground floor and middle floors, while the higher one carries people moving between the higher floors. Since some people will need to go all the way from the bottom to the top, most buildings with TWIN systems also include one or two shafts with a single car to support long rides. Riders select their destination floor on the touch screen of a central console, called a destination dispatch, and then get directed to the correct elevator. When traffic is low, one of the cars in a twin shaft can park at the top to allow more freedom of movement to the remaining car. Smart software keeps the system organized – it groups riders together based on how far they are going and carefully monitors the space between cars so they don’t crash. If the cabins get too close, they will automatically stop at least one floor apart. As of 2019, TWIN systems had been installed in fifty different buildings around the world.

Up and Down and Sideways

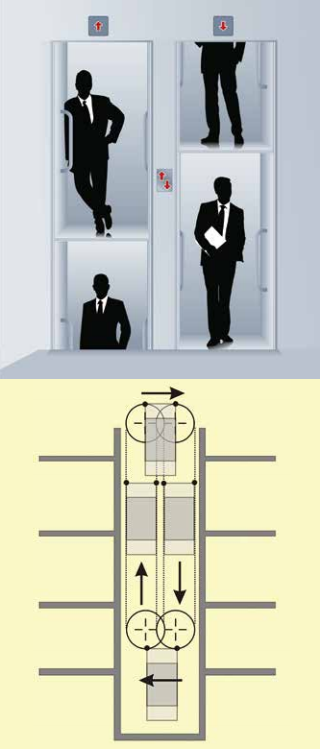

What’s better than two elevator cars in a shaft? Multiple cars that go up, down, and sideways, all throughout a building. In 2017, ThyssenKrupp announced its MULTI elevator system. Instead of a single vertical shaft, this elevator system is shaped like a rectangle or grid. The cars circulate inside. Since a rope or cable system can only pull up or lower the cars, the MULTI works very differently from most elevators. It relies on a magnetic motion system similar to the one used by a maglev train. “What we did is we took a train and we adjusted it 90 degrees up and we put it into a shaft,” Andreas Schierenbeck, CEO of the elevator division at ThyssenKrupp, told Wired magazine. There is no rope pulling the car. Instead, a track running through each vertical and horizontal shaft acts as a linear motor . This track contains coils that generate a magnetic field . This field pushes the car quickly in a straight direction . If the car needs to change direction, it pauses at a junction between shafts, and the track rotates behind it while the car remains still. Then the magnetic fields start pushing again, but this time in a new direction.

Doing away with cables frees elevator cars to move much farther. “In theory, you could go up to infinity in any dimension,” Daniel Safarik, editor of the journal “Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitats” , told CNBC. In addition, fitting many cars into one looping shaft frees up space in a building. It’s like regular cars having a multi-lane highway instead of a single-lane dirt road. ThyssenKrupp estimates that a building using MULTI will have up to twenty- five percent more space available to use for apartments, offices, or shops.

In addition, allowing elevators to move in three dimensions opens up new possibilities for architecture. For example, architects might put dramatic sky bridges between buildings. MULTI elevators can move people up within a building, or across to other nearby buildings. “We’ve seen sky bridges in the past which in some buildings are more of an architectural gimmick, but now we can really use them,” said Michael Cesarz, CEO for MULTI at ThyssenKrupp.

In June 2017,Thyssenkrupp officials demonstrated a prototype of the MULTI elevator for a crowd. The first MULTI is currently being installed in the East Side Tower in Berlin, a skyscraper that should be completed by 2021.

Are any of these elevators as cool as the Wonkavator? Maybe not, but who knows what might be next in elevator technology!