Airplanes couldn’t take off. Ships and trucks couldn’t deliver products. Factories stopped running. Hospitals had to turn away patients. It was June 27, 2017, and an invisible enemy was attacking businesses around the world. That enemy was a computer virus. Security experts named it NotPetya because at first it seemed similar to a 2016 virus named Petya. But it was much worse than Petya. “It was the worst cyberattack ever,” says Craig Williams, a cybersecurity expert at Cisco in Austin, Texas.

Power stations and airports, farms and factories, hospitals and banks, these are all examples of critical infrastructure—they are the systems that keep society running smoothly. Today, almost all of these systems rely on computers, networks, and the Internet. Many also use industrial control systems, a combination of hardware and software that keeps equipment running. Any infrastructure that uses computer systems can be broken by a cyberattack. Cyberattacks on critical infrastructure are rare now but will likely become more common in the future. “The threat is absolutely growing,” says Robert M. Lee, a cybersecurity expert who founded Dragos, Inc.

Why might someone want to take down infrastructure? These attacks are often acts of war. One country attacks another in an attempt to steal or expose secrets, influence politics, or spread chaos and fear.

The World’s Worst Attack

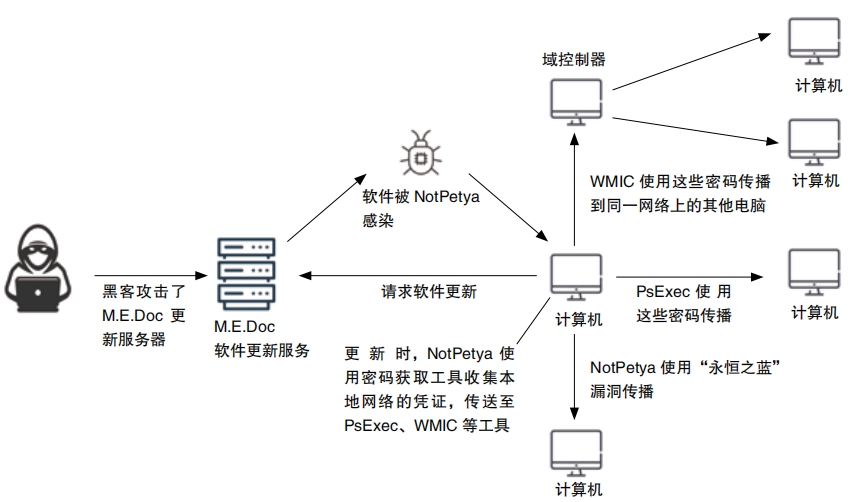

Williams and a team of other experts discovered that NotPetya began when hackers broke into the computer systems of a small company in Ukraine, M.E. Doc, that makes tax software for the country. Most companies that do business in Ukraine used this software. The hackers hid their virus into a routine software update. (M.E.Doc had no idea it was there. )

When people installed the update, they also installed the virus . Once inside a computer, the virus corrupted the Master Boot Record (so that the computer couldn’t start up normally) and Master File Table (so files couldn’t be read normally). Then the computer crashed, and as it started up again, the virus scrambled all the files. The next screen a person saw was a scary message in red text saying, “Your files are no longer accessible. ” The message instructed the user to pay to recover the files.

To a computer user, this seemed like a common type of virus called ransomware . (Ransom is the word for money paid to a criminal to return something that was stolen.) However, in this case, the ransom was a lie. “There was no chance to get anything back,” says Williams . NotPetya was actually wiper malware. It wiped everything out. Once the virus had infected one computer in a network, it quickly spread itself, taking down entire computer systems. It could spread thanks to a sneaky chunk of software called EternalBlue. This software took advantage of a vulnerability in the Windows operating system.

Many businesses around the world were left with no way to access their software and digital records. Their only option was to try to rebuild their systems from backups.

The Not Petya attack was entirely digital. But it had very real consequences . The digital attack impacted people’s health and safety. “People don’t realize how much they depend on computers until they suddenly break,” says Williams . “Life can come to a screeching halt. ” When Merck, a company that makes medicines, lost its control on computer systems, one of its factories had to stop making vaccines . That meant fewer vaccines were available for people who needed them. Some hospitals couldn’t treat patients because they couldn’t access their records.

At Maersk, an international shipping company, the digital attack slowed down the worldwide distribution of food, clothing, medicine, mechanical parts, and other products. One Maersk terminal in New Jersey handles tens of thousands of pounds of products every day. The terminal transfers shipping containers between trucks and ships. Barcodes on the containers link to a computer system that tells everyone where everything has to go . When NotPetya hit, the barcodes didn’t work. The system that tracked the containers no longer existed. Hundreds of trucks couldn’t deliver or pick up containers as planned because, without its computers, Maersk didn’t know what was in the containers or where they were supposed to go . Some containers remained stranded or lost for months after the attack.

In Ukraine, the country worst hit by the attack, “The government was dead,” said Volodymyr Omelyan, the country’s minister of infrastructure. Almost every single government agency in the country had no access to its computer systems. In addition, many banks, airports, power companies, and hospitals had lost their computers. ATMs and card payment systems at gas stations and stores were dead too.

Before NotPetya hit, Microsoft had already released patches for supported versions of Windows in March 2017 to address the EternalBlue vulnerability.

But as of June 2017, many companies had not yet installed the fix. Keeping systems up to date can prevent many cyberattacks. But even a completely updated system may suffer in a zero day attack, one that exploits a bug that cybersecurity experts don’t know about yet.

Battles in Cyberspace

Who were the hackers behind NotPetya? No one knows. The attack happened on a national holiday, when most people weren’t immediately available to respond. NotPetya likely spread much fartherthan its creators intended.

Not Petya wasn ’t the first cyberattack against Ukraine . In December 2015 and a year later in December 2016, blackouts hit the country. The second one took out the power to most of the capital city of Kiev for over an hour. These cyberattacks worked differently than NotPetya. Each one targeted the computer systems at specific power stations in Ukraine. To get into these systems in 2015, hackers sent phishing emails to people who worked for the power company . Phishing is when a hacker pretends to be a trusted company or person in order to trick a victim into handing over information or installing malware. This is like a bank robber tricking someone into giving him the key to the bank. In this case, victims opened an email attachment that installed malware on their computers. The malware opened a back door that gave the hackers access to the power grid’s computer systems . But they didn’t attack immediately. They used that backdoor for six months, completely unnoticed, as they studied the system. In 2015, the hackers manually typed in the commands to shut off the power at many substations . In 2016, they installed malware that shut off the power automatically.

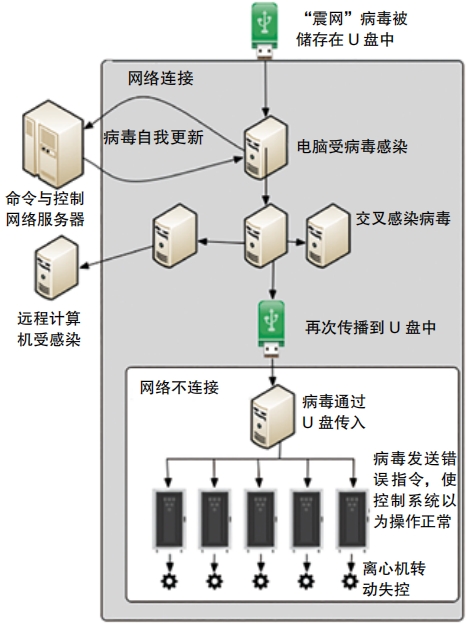

The first major cyberattack in the world that affected infrastructure was probably the Stuxnet virus . In 2010, it hit a facility in Iran that was making enriched uranium, a key ingredient in nuclear weapons. The virus caused machinery in the facility to stop working . Most experts believe the United States and Israel were behind the attack. Since then, there have been many reports of Iran and the United States battling in cyberspace. In 2013, an Iranian group claimed they had hacked into the control system for a dam in New York. They never did anything to open or close the dam, though. And in 2019, US officials said they had disabled computer systems that controlled Iranian rocket and missile launchers.

Governments employ teams of cybersecurity experts to watch for these types of attacks and catch hackers before they can do widespread damage. Companies such as Cisco and Dragos, Inc. also help keep an eye out for potential attacks. Lee investigated the blackouts in Ukraine. Attacks on infrastructure concern him, but he says, “The idea that all electric infrastructure is going to go dark in a cyberattack is not realistic … It’s not a doom and gloom scenario. ” It takes a lot of human effort, time, and resources to pull off an attack. If a company or organization has skilled human cyber security professionals keeping watch, then the risk of a successful attack won’t be as high.“Defenders have the upper hand,”he says.

Cyberwarfare in the Future

Defenders will have to stay on their toes to keep the upper hand. The Internet of Things is connecting more and more gadgets to the Internet and creating more and more interconnected systems. When new technology comes out, security often lags behind. Hackers have already found ways to get into smart TVs, baby monitors, and other connected devices . In a cyberwar, spies could hack into the TVs or home cameras of government or military officials. Terrorists could hack into the controls of self-driving cars or trucks or self-flying airplanes to take hostages or make the vehicles crash. They could potentially shut off water or power or Internet access in cities or towns.

The attacks that criminals launch will become smarter and more interconnected, too. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning allow computer systems to become better at a task over time. That means a virus could improve itself to become more damaging, more widespread, or more difficult to detect or remove. People may not need to control the attack at all. A smart cyberattack likely wouldn’t launch itself from one machine. More likely, the attack would begin with a group of infected devices (computers or phones or any connected gadget) called a hivenet or a swarm. The swarm could then attack many targets all at once.

Thankfully, criminals with destructive goals aren’t the only ones who know about these potential new ways to attack. Cybersecurity experts have access to the same AI and machine learning techniques and are working hard to build smarter, stronger defense tools. One way they do this is by running penetration tests. In these tests, a person tries to break into a system in order to uncover its problems and weaknesses. Then those problems can be fixed before an enemy finds them. Cybersecurity experts are already using AI to improve penetration testing. Companies and governments also sometimes run simulations of a cyberattack. Cybersecurity experts carry out an attack while other cybersecurity professionals defend. This is practice for a real act of cyberwar. “We as defenders have a lot of opportunities to keep systems safe and secure,” says Lee. We can never prevent all cyberattacks, but we can remain vigilant against them.