I didn’t set out to become a science writer. I wrote fantasy stories about magic portals and imaginary worlds all through grade school, high school, and college. But then I got an internship at a children’s magazine group, and all of their magazines were nonfiction. Toward the end of my internship, the science magazine’s editor wanted to profile a biometrics expert in one issue, and she asked me to do the interview. I agreed, but I was terrified. Would this person agree to talk to me? Would she know I’d never done this before? I knew nothing about biometrics . Would I sound stupid?

I emailed her, and she was happy to talk. I got myself a voice recorder, steeled my nerves, and called her. We spoke for about half an hour, and everything went great. But then I noticed that my recorder hadn’t started! And I hadn’t taken any notes! Terrified, I called her back and explained the situation. She patiently let me go through all the questions, all over again.

I learned several important things from this experience . Of course, I learned to always have a back-up method for recording and to always take notes. But I also learned that most scientists really want to share their work with the world. They are happy when someone takes an interest in what they do and wants to explain their ideas to others . Finally, I discovered something about myself: I enjoy learning about science. Biometrics hadn’t seemed interesting at first, but the more I talked to this expert, the more fascinated I became.

Soon, I was writing articles for the magazine nearly every month. That job grew into many others. Over the course of my career, I’ve spoken with hundreds of scientists. I talked to an expert on parallel universes while he shoveled snow from his driveway. I spoke with an elephant researcher while he was on the savanna watching a herd of elephants. I’ve visited robotics and geology labs and scientific conferences. I’ve written about space dust, zits, robots, and ghosts. Every time I tackle a new topic, I feel that same fascination I did while learning about biometrics for the first time. I love my job because of these feelings of discovery and wonder as I learn. If you also love learning, science writing could be a great career for you!

Loving learning isn’t enough, though. Proper research takes effort and practice . I believe that good learning is the key to good science writing. You must seek out sources of trustworthy information. And you must continue carefully researching your topic until you understand it thoroughly. Only then are you ready to explain it to someone else.

The Secrets of Successful Research

1.Use Google Wisely

I don’t know how I would do my job without the Internet. Searching for information online is an extremely important part of the writing process. It’s the first thing I do when I s it down to write about a new topic. I’ve learned many ways to use Google more effectively.

Let’s say I’m starting a story about biometrics. I won’t just type “biometrics” – that returns basic definitions . I’d type “biometrics news” or “biometrics breakthrough. ” This takes me to specific stories about things that are happening in the field.

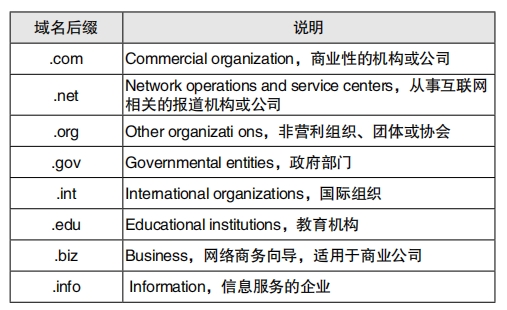

Still, I don’t just click on the very first search result. I look for several clues to help me understand if the page will be useful and trustworthy. The first clue is at the end of the URL. An ending of “ .org” indicates an organization, often a non-profit group or think tank. Government websites end in “ .gov” and universities or colleges end with “ .edu”. Groups of experts run all of these websites, and their motivation is usually to educate the public. They aren’t usually trying to make money off of website visitors.

URLs that end in “ .com”include companies, news websites, personal websites, social media, and so much more. I tend to avoid information on company pages and blogs, because the goal of the company is to sell its products. So they may leave out important information or skew the facts in an attempt to look good. Social media is also suspicious because people tend to share things without reading the entire story or thinking deeply. A personal website isn’t a great source because it’s unlikely that the person took the time to thoroughly fact-check their ideas.

Wikipedia is a special case. Many of the publishers I’ve worked for do not accept Wikipedia as a source because it is not professionally fact- checked. Volunteer editors contribute and check all of the information. I am more open-minded about this . I feel like the hive mind of all of these editors may actually be smarter than the few experts who put together a print encyclopedia. That said, Wikipedia should never be your only or final source. It’s a great place to start learning about a topic, though. And you can click the citations to find even more detailed information.

News organizations are usually excellent sources, but some sites that look like news aren’t very careful about what they publish. You want to find news sites that value facts and the truth over clickbait and advertising. My general rule of thumb is to prefer websites for larger and older news organizations. When it comes to science news, my favorites are the journal Science, Science News, National Geographic, New Scientist, Scientific American, and MIT Technology Review. One great thing about news sources is that they usually contain the names of experts. We’ll talk more about what to do with these names in step 4. They also contain links to original research or further information. These are paths to finding out more about your topic. I always follow these links.

2.Search Press Releases and Google Scholar

A general search will get you started on the path to thoroughly understanding your topic. But what you really need are the original sources of knowledge—the experts who are actively studying the topic and creating new knowledge. These experts publish their findings in academic journals or books. Unfortunately, you have to pay to access some of these articles and chapters. But more and more researchers are making their work open-source, meaning freely available to everyone. Also, if you can’t access an article you need, you can always reach out to the corresponding author. If you explain that you are a writer who wants access, they’ll usually send you a copy.

Another way to look for interesting research is to search press releases. These are short news articles that research institutions write to try to catch the attention of the media. The sites EurekAlert! and LiveScience are aggregators that gather many science news press releases in one spot, making it easy to search for news about your topic.

Actually reading a scientific research paper is a daunting task. Many are chock full of scary-looking mathematical formulas and technical language. But you don’t have to read the entire thing from start to finish. I usually read the abstract and introduction, then skip to the results and discussion at the end. Finally, I’ll go back and read the middle as best I can. If I can’t understand something, I jot down a question so I can ask the researcher.

3.Use Libraries

Libraries may seem old – fashioned, but they aren’t just buildings full of books. Libraries are an important community hub for finding knowledge about anything and everything . And librarians are trained to help you find what you need. If you have access to a library, use it! You could go in person and talk to a librarian. But most libraries also have online catalogs of materials, often including e-books that you can download and start reading immediately.

For me, learning from a book is very different from learning online. When I learn online, I tend to search for very specific answers, and I read just a few sentences or paragraphs at a time before skipping to something else. When I read a physical book, I don’t skip around as much. And I tend to discover ideas that I hadn’t considered looking for. I almost never finish reading an entire book when I am researching, because it would take far too long. But I read the chapters or sections that seem most important.

4.Seek and Interview Experts

I don’t talk to experts for every single thing I write. But taking the time for this step makes a huge difference . Speaking with experts is by far the most helpful and rewarding part of the research process. I still get a little nervous about contacting these strangers and asking them to spend some of their precious time talking to me. But I’m not as scared as I once was . I look forward to interviews because I always discover new things that Ididn’t expect to learn.

As I’m working through steps one to three, I save the names of experts that I come across . My list includes people who are quoted in news articles and books, the authors of scientific papers, and the authors of books. The next step is to Google each person to find out more about who they are and the focus of their work. If they still seem like someone I need to talk to, then I look for contact information. Professors usually post contact information on their website s or the websites of schools they work in. And most research papers contain contact information for at least one of the authors. If I can’t find an email address, I’ll reach out to an expert on LinkedIn or Twitter. As I’m searching, I take special care to seek out experts who have been traditionally underrepresented in science, including women and people of color.

When I reach out to these experts, I always introduce myself, describe the article I’m writing, and explain why that expert’s work is such a good fit for my project. If the expert agrees to an interview, I prepare questions.

Careful preparation is important. The more I know about the person’s research, the more nuanced the questions I can ask. However, I also regularly ask questions that I already know the answer to. I do this because I want to hear how the expert explains the answer—sometimes my understanding isn’t quite correct. Mainly, my goal during an interview is not to check off all my prepared questions, but to listen and understand. When the expert explains something complex, I repeat a summarized version of the idea back to them to make sure I understood correctly.

The first question I ask is usually something like, “How would you explain the results of your research to a twelve-year-old?” It’s often challenging for the researcher to answer, but it puts them in the mindset of explaining their work to someone with no background in their field. That mindset often lasts for the whole interview. I always ask them to describe concrete details from their research. I want to know what their equipment and research materials look, feel, and smell like. I want to know about funny mistakes or accidents that may have happened during their research. This type of information helps readers to visualize the researcher’s work and care about what they are doing, even if it is highly technical. Toward the end, I always ask, “Is there anything we didn’t talk about that you’d like to add?” This is a great question because you never know what you might have missed talking about.

I’m also open to discussing things that seem off topic. For example, I was once writing an article about how scientists have learned to measure and decipher brainwaves. I spoke to one researcher about her work in this area, and we got off on a tangent about reading. The reason she measures brainwaves is to figure out how kids learn to read. So I started asking about her research in this area . She told me that she had a bucket of toys and treats in her office to help keep her young research subjects motivated as they had EEG caps fitted and went through the reading exercises. I never would have thought to ask about that! I stayed in touch with her and wound up writing an entire new article about the science of reading a year later.

Conducting interviews in person is wonderful, but rarely possible. Video calls on Zoom or Skype are almost as good as in-person meetings . If that won’t work, I call the person on the phone. In rare cases, I’ll send questions via email, but I don’t like this method unless I just have one or two simple questions. Having a real conversation is a much better way to learn.

Share Your Knowledge

If you’ve followed all the steps above,you’re ready to write something. As I’m writing, I have my notes open. I also continue to search Google as ideas come up that I hadn’t considered while researching. When I’ve finished a draft of the story, I’m not done. I still have to edit and fact-check.

Fact-checking is very important. Professional news organizations typically e mploy fact-checke rs who go through every story before publication to make sure everything is correct. Even if you got your information from trustworthy sources, it’s possible that those sources made a mistake or that the information is now out of date. So you should always look for multiple sources that agree. And you should check the date on your source material to make sure it isn’t too old. I also ask the experts that I interview to look over the part of my story that mentions them and their work. That way, they can tell me if I’ve gotten anything wrong. I may also seek commentary sources. These are experts who are not the authors of the research I’m writing about. I ask them if the research seems correct or if there is anything that concerns them. If you’ve researched and written something about science, then you are a science communicator! Congratulations. The world needs more people who know how to seek out trustworthy information and turn it into engaging writing. Thinking critically and checking the facts of everything you read takes time and effort. But this effort is the only antidote for fear and fake news. The world needs more people to share real, factual scientific discoveries with the world. Check out the #scicomm hashtag on social media to meet others who care about sharing science with all of society.